Carrying the Torch in the Fight Against Neglected Diseases

Luis Pizarro, a Chilean physician who has led medical projects for several years in West and Central Africa, was named this week as the new executive director of the international non-profit medical research organization Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative.

DNDi was launched in 2003 when Médecins Sans Frontières teamed up with research institutes from Brazil, India, Kenya, and Malaysia to respond to the frustration doctors around the world faced with medicines that were ineffective, unsafe, unaffordable—or that had never been developed at all. MSF dedicated a portion of its 1999 Nobel Peace Prize award to exploring a new, alternative, not-for-profit model for developing drugs for neglected populations.

Pizarro’s predecessor, founder Bernard Pécoul, led the organization to the development and delivery of 12 new treatments for 6 deadly neglected diseases, including sleeping sickness, leishmaniasis, and young children and infants with HIV.

Under the leadership of Pizarro, DNDi aims to deliver another 13 treatments by 2028.

Pizarro spoke with GHN about how neglected disease treatments are developed, how that approach can be applied to pandemic preparedness, and reasons to be hopeful about the quest to stamp out NTDs.

How did your career in global health lead you to this role at DNDi?

My first mission was in Niger, working with a French NGO called Solthis to support the country’s national HIV program in 2004.

I became convinced that I wanted to support national actors to support their own national programs.

Most physicians in my field first started with very vertical disease programs with specific funding, and we realize now that if we want to reach the most neglected populations in very rural areas, in decentralized sectors, we need to strengthen primary care facilities and try to think how NTDs can be integrated into those plans. So that's what I did for almost 12 years.

Neglected disease research is up against a lot of obstacles. How does a new drug for a neglected disease come about?

Yes there are obstacles but DNDi has a wealth of experience to show that it is possible to develop innovative drugs for the most neglected populations, even if they do not constitute a traditional “market” for the pharmaceutical indstury. DNDi has focused on 2 approaches—repurposing drugs that already exist, while searching for new ones.

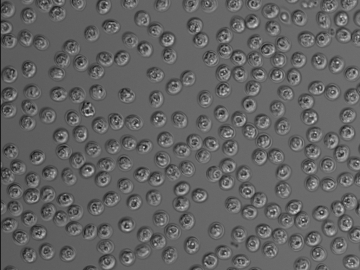

Take sleeping sickness (human African trypanosomiasis). When DNDi started working on that disease, treatments were toxic and difficult to administer.

At the time, treatment was done with a treatment based on arsenic, known as “fire in the veins” and which killed 1 in 20 patients. When we were created in 2003 one of most immediate concerns was ending this unjust situation and focusing on the short-term. We immediately got to work and asked ourselves: ‘OK do we know a drug that can be repurposed or adapted now to address this problem?’

Even though our eventual goal was an all-oral treatment for sleeping sickness, we had to focus first on the short-term. So we developed a 2-drug treatment known as NECT, and within 3-4 years we had a treatment that was safe and effective.

But that’s an IV treatment with a lot of logistic complexity to deliver, especially for sleeping sickness patients that live in very remote areas of countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

So parallel to this we were thinking about a new oral treatment—and 10 years later we have fexinidazole, a 100% oral treatment that is completely safe.

And next year we hope to bring a new drug that will treat sleeping sickness with just one dose and bring us closer to eliminating the disease.

We plan on replicating this success for other neglected diseases, such as leishmaniasis, a disease that is difficult to treat and for which some treatments are toxic and expensive. We have also just launched a new dengue program that applies the same strategy of repurposing drugs while looking for new ones.

What can pandemic preparedness systems learn from this approach to tackling neglected diseases?

COVID is not the last pandemic we will face, and the model we have been trying to apply to neglected diseases should also be applied to anticipate what is coming. We must not repeat history with another crisis in innovation and access, as seen during the global HIV response or COVID vaccine inequality.

That means having a robust pipeline of clinical trials for new drugs in the countries most affected by a given disease.

We also need to be reactive to those trial results, and engage with regulatory agencies in those countries to make the results of those trials available quickly. We can’t be over-reliant on agencies like the (US) FDA—that’s not reactive enough—because clinical trials are happening in other countries.

And third, we need to work with local manufacturers to ensure those products are distributed very quickly.

How has the effort to stamp out NTDs evolved over time?

When DNDi was founded 20 years ago, there was very little R&D for neglected diseases—there was little incentive for the pharmaceutical industry to conduct R&D for neglected populations.

To remedy this situation, DNDi started with national research programs in countries most affected by neglected diseases: in Brazil: Fiocruz, in Kenya, Kemri; in India, ICMR (India Council of Medical Research). These are research-grounded field organizations that pointed to where the problems were—and 20 years ago these programs were very new. They are now an essential part of the DNDi model and keep us focused on patient-needs.

After all, we are patient-need driven in all of our activities and we try to add to a more global picture. But we need to be humble—we are not the only organization working in this way.

One key to DNDi’s model is that it’s not about choosing the private or public sector. It’s not that the pharma industry has bad intentions, and it’s not that the public sector will be the solution. It is about finding the middle ground.

For example, a sleeping sickness patient would not be a potential customer for the pharma industry. But there’s an added value of being the chef d’orchestre, so to speak, of this R&D—you have Sanofi around the table, you have the Congolese Ministry of Health; the Gates Foundation... This dynamic was really a challenge at the beginning for DNDi, but bringing these partners together is now a key to our successes. it’s about how everybody works together for a common good.

Why should ordinary people care about neglected diseases in other countries than their own?

Twenty years ago, nobody really cared about the health situation in low-income countries.

Climate change and the COVID crisis are increasing the understanding that we are connected, that diseases become global. Successive pandemics have shown how interconnected we are.

WHO has developed a list of diseases that have pandemic potential. Investing in neglected diseases of neglected populations is for sure about anticipating the way those diseases are evolving.

Why should we be hopeful about the future of the fight against neglected diseases?

I have seen real people committed to working together, and I’m 100% sure that this collective effort is not just a politically correct effort.

For 20 years, DNDi has shown the benefits of starting from the needs of the patient, discussing with them: How do you want to have a drug? Once a day? Is it oral or intravenous? Do you want an injectable one? It’s about really discussing, with doctors, nurses, and patients, what is the drug that we should look for.

For our next 20 years we will continue to work closely with the patients to develop treatments tailored to their needs – this gives me hope for other deeply neglected populations.

Stakeholders sometimes spend 8, 9, 10 years on this this effort, and that effort is not just about money—but about human engagement efforts to keep it going long term. It’s a lot of work, but in the end it works.

That gives a lot of hope for how we can handle new diseases.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in over 170 countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

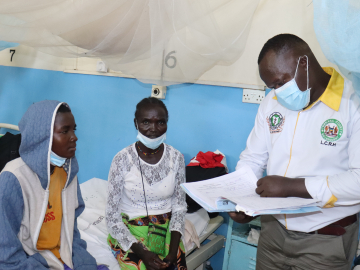

Luis Pizarro at Kimpese hospital in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where DNDi undertook several studies to develop drugs for sleeping sickness and river blindness. June 2022. Kenny Mbala/DNDi