Neglected Diseases Are Fierce, But So Is Monique Wasunna

NEW ORLEANS—“If you have not met her yet, you should.”

That’s how ASTMH President Linnie Golightly, MD, introduced Africa Ambassador for DNDi Monique Wasunna, MBBS, MSc, PhD, in a news release announcing her as the keynote speaker for the American Society of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene’s annual meeting last week. “Her career embodies what we do here at ASTMH: Leverage the best of science and medicine to tackle some of the world’s most neglected health challenges,” Golightly added.

Wasunna lived up to the intro. In a lively speech, she gave a stirring call to action for the global health community to fight the imperialism and inequities that have held back progress and celebrate the force of African scientific leadership—themes she elaborated upon in a Q&A with GHN on the conference sidelines.

In her current role, Wasunna, who is also the founding chair of the Leishmaniasis East Africa Platform, focuses on DNDi’s mission to improve treatment access and eliminate neglected diseases through R&D collaborations benefiting vulnerable populations.

As a young doctor, Wasunna treated patients with neglected diseases such as visceral leishmaniasis—experiences that affected the course of her career. She told GHN about the relatives and patients who led her to take on the most stubborn neglected diseases, the hurdles yet to be overcome, and her hope that more young people will take up her passion and ask how they, too, can make a difference.

What inspired you to focus so much of your career on neglected diseases?

My sister, Hope, is the reason I went into medicine. As I shared in my keynote, she was very sick, and my mother was always distraught. But the reason I decided to focus on neglected diseases is another story.

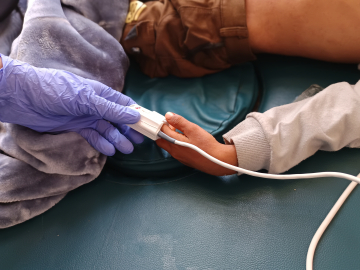

After I finished medical school and completed my internship, I joined the Kenya Medical Research Institute, and I did my rounds every morning in the Mbagathi district hospital. One of the patients, an 11-year-old boy with visceral leishmaniasis, came in with a distended abdomen, fever, everything, and he was not responding to treatment. I used to check on him every day as I was going home; we were such friends.

One day, I took one look at him and knew I had to get him to the referral hospital, Kenyatta National Hospital in Nairobi. An ambulance wasn’t available, but I just thought, I can’t let him die, so a nurse and I took him in my car. I drove like a madwoman through Nairobi traffic, and then we ran through the hospital, carrying the boy in our arms. But when we got to the emergency department, we realized that he had literally died in our arms. I was so devastated. And I said to myself, this disease that has taken my friend, I will do anything in my power to help other patients. I will be their advocate. My mind was made up. Leishmaniasis it was, NTDs it was.

Tell us about the effort to eliminate leishmaniasis.

DNDi developed the Leishmaniasis East Africa Platform in Khartoum, Sudan, in 2003. DNDi was founded in July 2003; by August, we were in Sudan. When people are dying, you can’t waste time!

For the clinical trials, we partnered with Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia, and Sudan, and in 2004 we launched the first—a combo of SSG (sodium stibogluconate, an old leishmaniasis drug and the existing treatment at that time) and PM (paromomycin, an injectable used to treat other infections that had some anti-Leishmania activity). In Sudan, it took a while to get the right dose down, but eventually we confirmed that that combination worked as well as SSG alone—and faster, taking just 17 days compared to the 30 days needed for SSG. Sudan’s Minister of Health said, “My people have been dying, and this medicine works—and it is cheaper and works faster—and from tomorrow I want you to be using this medicine.”

And that’s what happened: The medicine was used in Sudan without guidelines. Eventually, the medicine was registered and recommended as the first-line treatment for the region, in 2010. Later, we developed another combination—paromomycin and miltefosine— confirmed to work even faster, in 14 days. Now, we are just waiting for the WHO to change their treatment guidelines—a decision could come at any time—and then for health ministries to change their policies.

All this time, we have been tackling the low-hanging fruit—using existing drugs. But at the same time, we—DNDi, with our partners—have also been developing new treatments from scratch. Now, 20 years later, we have three new products in or heading into trials, including an oral treatment in a Phase 2 trial in Ethiopia.

If you had to name one NTD likely to hit the global elimination milestone next, what would it be?

Sleeping sickness. We’ve come a long way. Actually, now, the number of patients is really reduced. I think Guinea is on the way to elimination; I think that will be announced anytime. And in DRC, the patients have come down. With acoziborole—a one-pill treatment that can safely be given to people who don’t have the disease, unlike the earlier option, melarsoprol—an arsenic compound that patients say feels like “fire in the veins,” and killed 1 in 20 patients. And now, we also have fexinidazole, a 10-day oral treatment. It’s a new chemical entity, developed from scratch, that can treat not only stage 1 of sleeping sickness, but stage 2, when the infection crosses the blood-brain barrier.

Which diseases frustrate you the most because they persist, despite being largely preventable or treatable—and what are the obstacles?

Leishmaniasis: It looks easy to tackle, but it’s difficult—because it affects the poorest of the poor. Another example is HIV-VL coinfections. Patients with HIV are immune suppressed, so they are prone to getting leishmaniasis. In Ethiopia, DNDi estimates that 20%–30% of patients with VL also have HIV. Coinfected HIV-VL patients are difficult to diagnose, difficult to treat; they have a lot of relapses. But we have a combination for them that passed a clinical trial in Ethiopia, which the Ethiopian government has already registered.

For all neglected diseases, funding is a problem. To reach people living in the middle of nowhere, to travel to those remote areas, you really need to have a lot of passion. The roads don’t even exist. There are big ditches. Any mistake, and your car goes down there, you’re dead. If it’s raining, you stop and just hope nobody comes and knocks you down the cliff. Before you can do credible research, you must spend money to improve all the infrastructure—the roads, hospitals. The infrastructure is being improved now, but it is still a big challenge. Attracting doctors and researchers to go and work there is another big challenge.

Are there donors who recognize this and are addressing the infrastructure hurdles?

Some donors do not want to support things like infrastructure, but it is so necessary—otherwise you’re not going to retain young doctors. They’ve come from urban areas, where their lives are good and everything is available, and then they’re put in the middle of nowhere with hardly any running water or electricity. You have to fix that before you can even think about starting a clinical trial. Poor infrastructure can also put study participants at risk—and if a patient dies in a clinical trial, you can lose a good drug, because the death is counted as though it was caused by the drug—even if it was really caused by poor conditions.

In your ASTMH keynote, you mentioned that there are so many more African research institutes than when you got your start. What barriers still need to be overcome?

As we’ve gone along, we’ve been building capacity—to conduct clinical trials, and for diagnostics. We still need better tests. There are efforts to develop them, but for many diseases, including leishmaniasis, they are still limited.

Another barrier is money. Africa has researchers who are well-trained, and if you don’t compensate them well, they will leave because they’re always being recruited by the North. When I trained at the London School The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, I could have stayed in Europe, but I wanted to go back, to give back. I decided to stay, whatever it takes. Knowing that you touched somebody’s life, you helped save somebody’s life—it’s an amazing feeling.

Leadership is key, and African leadership is key. And I think more women need to get into this space. With women, many start looking after their brothers and sisters, and some of them go on to have their own children … and they really know the pain of losing someone they’ve taken care of. If you have those people as leaders, it makes a difference. I do think there’s a concerted effort to build that leadership. In my own country, there are now more women who are governors, MPs. Kenya is not perfect, but we’re trying. We need to continue to encourage that.

How can the U.S. and other governments be better partners for African research institutions?

For NTDs, it would be nice to have more funding partners. Also, many donors are moving more toward funding projects, rather than funding for entities. If you cover treatment for a given number of patients, but you don’t fix the infrastructure, it’s just a temporary fix. Fund the entities, give the grantee a little leeway.

What progress do you hope comes out of the ASTMH meeting?

There were many young people here, and they’ve been very inquisitive, asking lots of questions, which has been great to see. I hope they take the message to heart that we need to work together to eliminate neglected diseases in vulnerable populations. If young people take up that passion and reflect upon what their contributions will be, and ask how they can make a difference, we can succeed. And what a world that would be.

This Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

Monique Wasunna delivering a keynote address at the ASTMH annual meeting in New Orleans, November 13. Brian W. Simpson