Fighting Infant Mortality With Vaccines and Cash in Northern Nigeria

SOKOTO, Nigeria—The thick, heavy air carries the faint scent of antiseptic as late morning sunlight filters through the tiny window of Farfaru’s primary health care center, casting a shadow over Sha’atu Bala’s forehead. Bala tightens her grip on her five-month-old baby, Umaru, who stirs against her chest as if sensing some uneasiness.

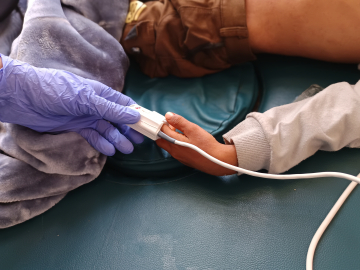

Across from her, Halima Tukur, a health worker, hunches forward and gently rolls up the baby’s short sleeve. Next, Tukur gently taps the syringe twice, forcing out a tiny bead of liquid, but before the needle even pricks his skin, the baby lets out a loud, piercing cry.

“Yan hakuri (sorry!),” the health worker mutters in local Hausa, a language spoken in the country’s northern region. She then opens his mouth and squeezes two drops of novel oral polio vaccine on his tongue.

Nearby, Rukayya Atiku, a field officer for the New Incentives program, verifies Bala’s vaccination card against the records on her phone before taking a photo of her with the child. She then hands her $0.66 (NGN 1,000)—a cash reward that the nonprofit gives mothers to boost vaccination rates in northern Nigeria.

“Before, I used to walk from my home to this clinic, sweating under the hot sun. But with the cash reward, I can hail an okada (a motorcycle taxi) to and from the clinic, saving me time and energy,” Bala says, flashing the Naira note. “l will use the rest to buy paracetamol.” She’ll get an additional $3.3 (NGN 5,000) if she completes all of her baby’s scheduled doses.

A health worker vaccinates a child in the Farfaru clinic in nothern Nigeria. Abiodun Jamiu

The introduction of New Incentive’s cash rewards program in 2014 spurred a surge in the number of mothers bringing their children for vaccinations. The clinic now attends to approximately 30 to 40 babies a day, according to Tukur—a stark departure from the past, when workers often had to go out and persuade women to bring their children for vaccinations. The initiative, part of the All Babies Are Equal program, is funded through GiveWell and is aimed at addressing Nigeria’s severe infant mortality crisis. It operates in government-run health facilities across 11 northern states—where vaccine hesitancy and misinformation run rampant.

The hesitancy peaked after Pfizer’s failed vaccine trial in 1996, which resulted in the deaths of 11 children and left others with disabilities and left some people fearful about vaccines. Other people are poor and focused on daily survival, or live in hard-to-reach communities and lack the means to take their children to the nearest health facilities for vaccination. Insecurity has also hindered immunization efforts. Missed vaccinations contribute to rising infant mortality rates in the country: At least 41% of Nigeria’s deaths among children under 5, from causes such as diarrheal diseases, lower respiratory infections, and meningitis, could have been prevented with vaccines, according to a 2019 study.

As of 2022 approximately 2.2 million children in Nigeria had not been immunized—constituting the second largest population of zero-dose (never–vaccinated) children globally. Within Nigeria, immunization coverage is lowest in northern areas, where conflict and displacement have hindered uptake.

In areas where there are still pockets of hesitancy, the cash rewards initiative works with local authorities relying on traditional and religious leaders who wield immense influence among local communities to raise awareness about the benefits of vaccination

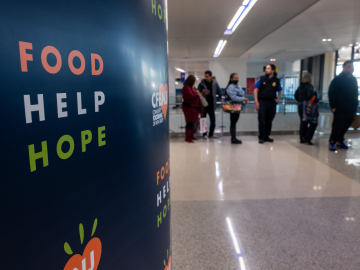

Women wait with their children to be vaccinated in Farfaru’s primary health care center. Abiodun Jamiu

“It’s more than just the cash,” Mubarak Bawa, the operation director, adds. “When we go into a community, we conduct a rapid assessment to survey the level of compliance, which guides us before we go into the villages to sensitize locals about routine immunization and demystify rooted misconceptions about immunisation.”

Before the team of local vaccinators visited her village in the Badon Haya area of Sokoto, Nana Umar’s husband wouldn’t allow her to take any of her children for vaccination. Like many others in the village, he believed immunization could cause infertility. His wife also recalls how he once said, his voice laced with doubt, “Our forebears lived longer without immunization, so why should new babies be vaccinated?”

But that wasn't the worst of it.

“Sometimes, they mock us [mothers who take their babies for vaccination],” she says, “especially when the baby gets the 40-day shot [the pentavalent vaccine, or 5-in-1-shot, that protects against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (whooping cough), hepatitis B, and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib)] and cries loudly. They used to say, ‘you tortured this child; you took him to be injected.’ Some mothers refuse to vaccinate their children because of the crying, saying the baby will cry day and night and won’t let them sleep, or will develop a fever.”

Umar’s husband opposition to vaccines loosened when a team of local vaccinators visited the community for a sensitization outreach. Around the same time, their baby fell ill and was treated at the Farfaru health facility. “After she recovered, he started allowing me to come here, because he had seen the benefits,” Umar says.

While the initiative is commendable, it’s only good as a short-term measure says Tanimola Akande, a professor of public health at north-central Nigeria’s University of Ilorin. “The strategy is not sustainable. There is also a risk of caregivers growing dependent on this measure, which may lead to serious setbacks when such incentives are no longer made available.”

For now, there’s no set timeline—and New Incentive recently got another GiveWell grant. However, because the project is donor-funded, there are palpable concerns in the current climate of global aid funding cuts. Internally, insecurity keeps spreading across rural communities in northern Nigeria. As Bawa rightfully said, they only operate where it's deemed safe. That will no doubt cut children in these hotspots from the initiative (if they’re unable to move to safer areas). And, Bawa confirms, scaling their activities to communities plagued by insecurity has been a key challenge: Mothers in these affected communities are often cut off from the life-saving interventions.

Also, as more mothers bring their children for vaccinations, it puts a strain on the country’s already weak health systems. There simply aren’t enough workers to keep up with the growing demand.

Ed. Note: This article is part of Global Health NOW’s Local Reporting Initiative, made possible through the generous support of loyal GHN readers. Abiodun Jamiu is a freelance journalist based in Abuja, Nigeria.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

A mother holds up the cash incentive she received at the Farfaru clinic upon vaccinating her child. Sokoto, Nigeria. February April 2025. Abiodun Jamiu