The Road Ahead for the Most Neglected Disease

There is a saying that neglected diseases “begin where the road ends.”

These diseases of poverty strike the most marginalized populations and strain to attract the resources, funding, and attention of a world that is saturated by increasingly convoluted problems.

Gaining visibility for neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) takes tireless and impassioned advocates — like Ahmed Fahal, a Sudanese surgeon and professor who has spent 3 decades bringing the devastating disease, mycetoma, to the world’s attention. NTDs create lifelong, community-wide debilitation and contribute to cyclic, intergenerational poverty in families, but Fahal’s efforts show how advocacy can make a difference in breaking the cycle.

Mehreen Qureshi and I, both graduate students at the New York University College of Global Public Health, first read about Fahal in an article about an upcoming clinical trial spearheaded by my employer, the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), in partnership with the Mycetoma Research Centre (MRC) at the University of Khartoum. This led us to the GHN series where we found ourselves inextricably drawn to these patients in Sudan, whose lives were so heavily impacted by this truly neglected disease — enough so that we emailed Fahal directly. We pressed “send” at 3AM local Sudanese time; he responded within an hour. What ensued was a multi-week dialogue that drew us even closer to the disease and the communities, and convinced us to make the trip ourselves to the MRC.

The roadmap for mycetoma control and prevention began with experts calling for basic surveillance. In an effort to contribute and establish a solid base knowledge of the epidemiology of the disease to inform targeted prevention recommendations, we designed an mHealth-based surveillance and case management platform using CommCare, which had the capability to record basic demographics, address differential diagnoses, flag referrals, allow for follow-up, and run offline. With an implementation plan for a proof-of-concept study in hand, we ran into one final hurdle: funding. Unable to find buy-in at our graduate school (given liability concerns), we floundered until a fortuitous introduction to the Sudanese American Medical Association, which pledged formal sponsorship for our pilot surveillance project.

In August 2016, just 3 months after the 69th World Health Assembly officially placed mycetoma on the NTD list, we found ourselves on a long, disorienting bus ride along the Blue Nile with Fahal and a team of passionate physicians and medical students who volunteered to help us with our pilot study. Early the next day we arranged ourselves into groups composed of a surveillance team (a physician to diagnose and two app operators to triage cases/non-cases), an environmental team (tasked with taking meticulous notes and pictures of the environment in order to identify presumptive points of intervention), and a community influencer.

The next 72 hours were a whirlwind of activity covering 6 villages and 2 schools, and registering upwards of 500 patients, 125 of which were suspected to have mycetoma. At the end of each day we held meetings with the team and community members. The feedback and discussions emerging from these meetings led to refinement of the surveillance system, identification of bottlenecks, and viable interventions to explore.

Back in Khartoum, we worked with Fahal to unpack our experience, distill bottlenecks to care, offer recommendations to create an enabling environment for patients to seek care early on, and suggest next steps towards building an evidence base for mycetoma control. Culminating in a conference at Soba University Hospital, we presented our preliminary results, takeaways, and recommendations to a diverse audience of stakeholders including Naeema Al-Gasseer, the WHO representative in Sudan.

By the end of the conference, we had received commitments of collaboration and support, laying the bedrock for our 3-arm study on preventive interventions, building toward a comprehensive mycetoma control program. Coupled with the deployment of the finalized surveillance system across mycetoma treatment centers, improved disease estimates will lead to more targeted interventions.

Our experiences were tremendous, but we recognize that this is only the beginning. Mycetoma and those it impacts must continue to capture the attention of scientists and researchers who can help populate the treatment pipeline (through MycetOS) and expand vital social support programs that offset direct and indirect medical costs and chip away at corrosive stigma.

Advocacy and an ever-growing network of passionate collaborators can break the cycle of poverty, making the elimination of diseases like mycetoma a real possibility. Our confidence in this is rooted in our own experiences, and the thrill of having witnessed the birth of a worldwide ‘mycetoma movement.’

Ezra Jerome, MPH is a program associate at Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi). He traveled to Sudan while earning his MPH in Community and International Health at New York University.

Join the tens of thousands of subscribers who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday enewsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues: http://www.globalhealthnow.org/subscribe.html

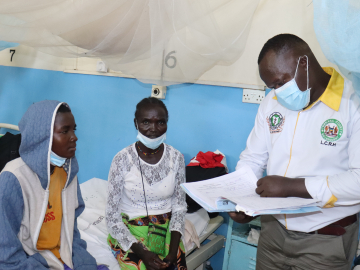

Children in Sennar State, Sudan, a country afflicted by mycetoma. Image Courtesy of Ezra Jerome and Mehreen Qureshi