Fighting Cholera Shame to Save Lives in Zambia

LUSAKA—Mary Kapaipi lost her husband to cholera in January, a death she believes was entirely avoidable.

Victor Musesho, 49, had left work early after feeling unwell, and later refused to eat dinner at their home in Garden House Compound. Kapaipi, 43, grew suspicious that he might be suffering from cholera after his friends noted his frequent trips to the toilet, but he insisted it was just a sore throat.

Later that night, Kapaipi found him vomiting outside their home. By the time she was able to send for help it was too late. Musesho died in the early hours of the morning.

The cholera outbreak that swept Zambia in early 2024 highlighted the urgent need for improved water and sanitation infrastructure, especially in urban areas. But the crisis spotlighted another critical factor, too: the stigma surrounding the disease.

In the days after his death, Kapaipi discovered Musesho’s soiled underwear hidden around their house, along with patches of white vomit concealed behind furniture. “My husband could have been sick for about two days, but he did everything to hide it,” says Kapaipi, tears brimming in her eyes. If he hadn’t concealed his symptoms, he might have lived, she says.

For Kapaipi, her husband’s secrecy and shame only added to her grief because his reluctance to seek help may have ultimately cost him his life. And this is a common pattern among cholera patients.

Sanny Mulubale, PhD, a lecturer in the University of Zambia’s Department of Social Sciences, thinks the real death toll during Zambia’s cholera outbreak was actually “double or triple” the 740 reported by the government, and that half of the deaths could have been avoided if stigma and shame were not a factor.

“It’s a very serious problem, and men especially have very poor health-seeking behavior for diseases such as cholera,” says Mulubale. “We are always told a man should not show any signs of weakness, men are not wanting to embarrass themselves.”

“The stigma associated with it makes things worse. Cholera makes you think dirty, it makes you think of fecal matter and drinking contaminated water. Nobody wants to be seen as a person who is unclean,” Mulubale adds.

Zambia’s Ministry of Health has tackled the problem by implementing “robust awareness campaigns aimed at demystifying cholera and reducing stigma” and increasing the number of community health care workers, says Kabukabu Akufuna, a senior environmental health officer at Zambia’s National Public Health Institute. The National Cholera Task Force is also planning an awareness and preparedness campaign.

“These campaigns focus on educating communities about cholera transmission, prevention, and treatment,” says Akufuna.

In Lusaka’s informal settlements, some optimism surrounds the possibility of fewer cholera cases this rainy season, though locals credit their own preparation and community resilience over government interventions.

A man draws water from a shallow well in Garden Compound. Lusaka, Zambia, November 6. Freddie Clayton

Many residents have chosen to abandon the shallow wells, opting instead to walk long distances to fetch cleaner water. Others are sending children out of the urban centers to avoid exposure. And many, remembering the chaos caused by cholera at the beginning of the year, are already on high alert.

Henry Malufu, who lives in the informal settlement of Chaisa Compound, vividly remembers how the disease left him on the brink of death, and how medical help saved his life.

“The whole experience was terrible because I almost lost my life,” he says. “The reason why I was able to recover was because we were put on treatment and supported accordingly.”

Maureen Chilandwe, head of Garden House Compound’s Neighborhood Health Committee, said that people are preparing for the rainy season with greater care this year and that more people, including men, are seeking help, medication, and guidance from the clinic.

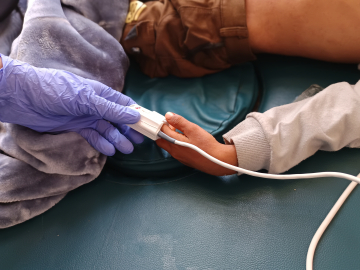

Women take their children to the health center in Garden Compound. Lusaka, Zambia, November 6. Freddie Clayton

“This time around, [people] are coming [to the health center],” she said. “They are keeping their surroundings clean in preparation for the rainy seasons. We don’t expect a lot of people to suffer this year now that we have those preventative measures. [We] know what to expect.”

While such proactive efforts offer a sense of hope that this season might be better, lasting progress in the community still hinges on the critical need for improved infrastructure.

Oliver Kaoma, MD, secretary-general of the Zambia Medical Association, champions efforts to raise awareness and reduce shame and stigma, whether they come from the government or the people.

But Koama believes that infrastructure remains key to solving the crisis, and that “a much more comprehensive and lasting approach is needed.” Residents should not have to walk long distances to collect water simply to lessen their chances of catching a deadly disease. As long as sanitation remains inadequate, the risk of cholera persists, no matter how much awareness is raised.

“We need to begin investing in water, sanitation, and hygiene infrastructure. The sooner we address these issues and allow people to access clean water, the sooner we will see a tremendous reduction” in outbreaks, Koama says.

These changes cannot come soon enough for families who fear losing a loved one. For others, like Kapai and her family, grieving the loss of a husband and father, they are already too late.

“Life has totally changed,” she says. “We would have done everything possible to save his life.”

Kennedy Phiri is a Zambian journalist reporting on environmental issues and the cofounder of Media Network Action on Climate Change.

Freddie Clayton is a British journalist who covers climate, the environment, and public health. He is a reporter for NBC News, and has written for The Guardian, The Economist, and the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Ed. Note: This article is the second in a two-part series; read Part I, Zambians Shaken by Cholera Outbreak Face Another Rainy Season, here. The series is part of Global Health NOW’s Local Reporting Initiative, made possible through the generous support of loyal GHN readers.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

Mary Kapaipi’s husband concealed his symptoms before dying the next day. Lusaka, Zambia, November 6. Freddie Clayton