Scotlandʼs Mission to Banish Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women globally—but in Scotland, an observational study of a national, school-based HPV vaccination program launched in 2008 detected zero cases of the disease among women fully immunized against HPV at age 12 or 13 years.

The study, which examined the medical records of 447,845 women born from January 1988 to June 1996, was led by Public Health Scotland and the Universities of Strathclyde and Edinburgh and published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Scotlandʼs school-based program offers the vaccine to girls, and since 2019, boys in S1 (the first year of secondary school) when they are aged 12-13 years. Pupils who do not take up the offer of vaccine are re-offered in later school years. This approach has consistently achieved an HPV vaccination of over 80% of Scottish pupils by the end of their fourth year of secondary school, when they are aged 15-16 years.

Across Europe, HPV vaccination coverage with the first dose, by age 15, was 40% in 2023.

The program has also demonstrated herd immunity benefits among unvaccinated girls, and strong evidence of reduced precancerous disease—changes to cervical cells that make them more likely to develop into cancer—among vaccinated women.

GHN spoke with Kirsty Roy, a lead author of the study, about what makes Scotlandʼs program successful, how it can still be improved, and the country’s goal to eliminate cervical cancer.

Cervical cancer can take 10–20 years to develop—what are the expectations for how these successes will play out long term?

Women vaccinated in 2008 as part of the school program were 26–27 years old at the time of our study.

Cervical cancer typically shows up in women aged 30–34, so the full impact of the HPV vaccine on cervical cancer rates will become more evident as vaccinated cohorts reach the typical age for cancer development. Scotland expects to see further declines in cervical cancer rates over the next few years as the first routinely vaccinated cohort reaches the peak risk age.

How do schools connect with families about the vaccination and screening program?

We know that four out of five adults are going to contract HPV at some point in their lives, and we know both males and females are susceptible. We also know the best way to prevent HPV is by delivering the vaccine, which is safe and effective at preventing cervical cancer.

We try to make sure that everybody has the same information, and that it is good information that will allow parents to make an informed decision about whether they want their child to be vaccinated.

A leaflet describing the HPV vaccine and consent forms are handed out in school. All resources are created centrally so you’re getting consistent messaging to every young person and their parents.

That messaging is integrated with schoolsʼ wellbeing curricula, and, at appropriate times, our young people will be educated about the importance of vaccines at all stages of life.

We also emphasize the importance of cervical screening—even for women who are vaccinated. The vaccines that we use cover most of the types of HPV associated with cervical cancer, but there are still some cancers that may develop, and some types that are not covered. The vaccines that we use cover the types of HPV most associated with cervical cancer, but there are still some types that are not covered and some cancers may develop in vaccinated individuals.

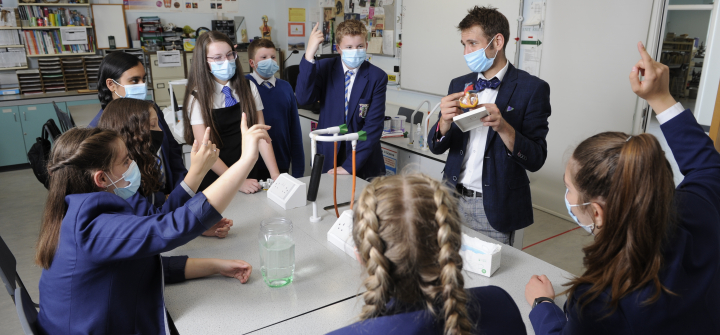

All school pupils in Scotland are offered the HPV vaccine in their first year of secondary school. Courtesy of Public Health Scotland

Are there other benefits of rooting the program in schools?

It increases vaccine uptake by making it accessible; it avoids the cost associated with traveling to a clinic or parents having to take time off. Itʼs also more efficient because you’re targeting a large group in a single setting.

And with all these efforts, what is the uptake of the HPV vaccine?

We have historically had very high levels of vaccine uptake. Today, by the end of S4—the fourth time a cohort has been offered the HPV vaccine—we tend to have an uptake that’s sitting above 80%.

That figure was above 90% until the 2015–2016 school year, when uptake began to decline.

Why do you think that is? Do you experience pockets of resistance, and how does Scotland address those?

We have vaccine inequalities in several areas that we are trying to address.

HPV vaccine uptake among boys has always been lower than girls, possibly because of its association with cervical cancer and the misperception that the vaccine only benefits girls. One of our priorities is increasing awareness about HPV being associated with other non-cervical cancers such as oral cancers, and genital warts.

Also, there is a widening gap in vaccination coverage between pupils living in the most and the least deprived areas. We also see some differences with certain ethnic groups and between rural and urban areas.

And particularly since the pandemic, uptake has been lower; is that because of COVID fatigue, vaccine fatigue? We know that school absenteeism is rising, especially in the most deprived areas. Can we target those groups outside the school setting if they’re not going to be in school? How do we counter online misinformation?

Inequalities also exist in the screening program, and we know that girls who are unvaccinated are also less likely to come forward for screening.

We are working to address these inequalities and ensure that everyone can access the vaccines for which they are eligible.

What is the ultimate goal of this program?

We are working towards eliminating cervical cancer in Scotland, as per the WHOʼs definition. We want to be able to see the impact of the vaccine on cervical cancer across all women in the population.

What can other countries learn from Scotlandʼs approach?

One of the key reasons that the program is successful in Scotland is it involves multiple organizations working with the shared goal of improving the uptake of vaccine, and we’re using consistent messaging.

I know from speaking with some colleagues in America that it may help to take the focus away from HPV being a sexually transmissible infection, emphasizing instead the fact that this is a vaccine that can prevent not just cervical cancers, but also penile and anal cancer, and genital warts. The vaccine has many benefits.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

All school pupils in Scotland are offered the HPV vaccine in their first year of secondary school. Courtesy of Public Health Scotland