From Displacement to Exploitation: Inside Brazil’s Human Trafficking Crisis

BOA VISTA, Brazil—“Water, sweets,” a young woman softly calls out to the passersby, as the scent of cotton candy lingers in the humid air.

A pair of children race around her legs while she cradles a sleeping infant.

Veronica* is one of approximately 680,000 Venezuelan migrants building new lives in Brazil. Sales from her carrinho (food stand) provide enough to rent a small house and support her children.

Nearly 8 million Venezuelans have fled their country in the past decade amid ongoing political and economic collapse. In the months following the contentious July 2024 re-election of President Nicolás Maduro, hundreds of Venezuelans arrive daily through a small Brazilian border town called Pacaraima. Some days see more than 600 new arrivals. Venezuelans made up half of the 194,000 migrants who entered Brazil in 2024.

Veronica pauses to watch pink wispy clouds as the sun sets over the Branco River. The scene emphasizes the city’s name, Boa Vista (Good View).

Yet behind the beauty of the capital of Roraima state lies a web of trafficking in drugs, weapons, gold, people, and organs. Wedged between Brazil’s borders with Venezuela and Guyana, the region has become a channel for migration that has exposed thousands of Venezuelans to exploitation.

A sunset in January over the Branco River in Roraima's capital city, Boa Vista (Good View). Image: Julianna Deutscher

“Invisible Chains”

The current migration has only intensified Roraima’s longstanding history of systemic exploitation, says Socorro Santos, director of the Roraima Legislative Assembly’s Defense of Human Rights and Citizenship Program.

For generations, illegal mining and deforestation groups have pushed Indigenous peoples from their land, says Marcia Maria de Oliveira, PhD, of the Universidade Federal de Roraima. This often pushes displaced people into forced labor and sex trafficking.

Today, Brazilian and Venezuelan criminal groups lure migrant men, women, and children to the garimpos (illegal gold mines) with false promises, only to trap them in modern slavery. Women are forced into sex work, often at the mines, posadas (motels), and restaurants.

Women are at high risk—especially mothers, who might succumb to traffickers because they are desperate to provide for their children no matter the cost.

Rodrigo Pereira Chagas, PhD, of the Universidade Federal de Roraima, recounts the case of Marcella* and Sofia*, Venezuelan women deceived by a fake receptionist job advertised online. When the pair arrived, the owner confiscated their phones and documents. Only Sofia’s hidden second phone enabled them to call for help and escape sexual exploitation.

Human trafficking can also extend to forced criminality, the sale of infants, illegal adoption, and the trade in human organs, according to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Migrants are often bound not by physical captivity but by “invisible chains”—fear for a loved one’s safety, dependence on shelter, language barriers, or the urgent need to feed their children.

David*, a middle-aged Venezuelan migrant, survived an arduous journey to Peru where he found work in a restaurant. He received no pay for six months of dishwashing. This prompted his return to Venezuela, and then a move to Brazil, where a farmer enticed him with the promise of a high-paying job in the fields. Forced to work under brutal conditions on the farm with little pay, he eventually left and now crosses daily into Guyana to work in a grocery store. On days off, he volunteers with a church program, assisting migrants applying for documentation and educating them on their rights.

Gangs also target Venezuelan youth, tricking them with the promise of putting food on the table. When young people are arrested, they often join gangs in prison as a means to survive, says Alba Marina Gonzalez Andrade, founder of the migrant advocacy group Voz Migrante. “First, they are arrested for stealing shampoo, the next time, it’s for drug trafficking,” she says.

While many migrants like Veronica manage to create a stable life for themselves, thousands live precariously. The lack of housing, food, and work heightens their vulnerability. The xenophobia of some Brazilians further limits employment opportunities and makes it difficult to access health care, housing, and social assistance programs.

Mayra Figueiras, founder of Humanidade Mais que Fronteiras, shares a pile of cards she plans to distribute with volunteers. "100" is the human rights hotline that can be called to report human trafficking. Image: Julianna Deutscher

Policy and Funding Shortfalls

When Brazil launched its fourth National Action Plan to Combat Trafficking in Persons in 2024, the government promised expanded services, stronger laws, and better protection strategies for migrants. Yet implementation remains slow. The Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela (R4V) estimates that 6,000+ Venezuelan migrants will need human trafficking protection services in Roraima alone this year.

“It’s easier to smuggle a person across the border than a bike,” says Aminadabi Dos Santos, coordinator of the Special Protection Department for the Secretariat of Labor and Social Welfare. He describes a system marked by the over-regulation of goods transportation and neglect of the movement of people.

“The federal government is trying to revive the national plan to combat trafficking,” Oliveira says, “but there are very few local policies supporting it or implementing it.” Efforts are underway to improve monitoring of human trafficking across borders, but the geographic terrain makes it challenging, says Thiago Pereira of the Federal Police Human Rights and Institutional Defense Department.

Data collection is another shortfall. Roraima lacks the financial and human resources to track trafficking statistics effectively, says Pereira. Recordkeeping should monitor types of trafficking, means and location of recruitment, prevalence disaggregated by regions, and demographics, including migration status.

Oliveira led a recent study which identified 309 cases of human trafficking in Roraima from 2022 to mid-2024. Of these, 73% were migrants—the majority of cases involved sex trafficking of women in the garimpos. The true prevalence, however, is suspected to be far greater. Pereira explains that, in addition to poor recordkeeping, cases are underreported due to fear of retribution from perpetrators and cases where individuals do not recognize themselves as victims.

Disque 100, Brazil’s government-sponsored human rights hotline, received at least one trafficking-related call daily in early 2024, although it’s unclear how many originated from Roraima.

When border crossings are involved, traffickers take victims toward Guyana, where support services are nearly nonexistent. Unlike Pacaraima, there are no shelters or international aid operations, making rescue challenging. Limited resources across the region result in government and UN agencies focusing their efforts at the main point of migration—the Venezuelan border.

Sister Valdelice Gomes of the Pastoral dos Migrantes, Diocese of Roraima, says many more resources are needed in Bonfim, the last Brazilian town before entering Guyana. She works with a group of volunteers assisting migrants with applications for social assistance programs and legal documentation. During these sessions, the team keeps a watchful eye for signs of human trafficking—a “friend” holding onto their identification documents, a partner answering questions while they sit quietly avoiding eye contact, the excitement of a job found on Facebook. When cases are identified, Sister Gomes reports to the police, social assistance centers, and the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

One of the volunteers recalls the case of a girl who looked no older than 14, accompanied by a man in his twenties who said he was her husband. The girl wouldn’t say how old she was, and the husband kept answering questions directed toward the girl. The volunteer went to alert Sister Gomes.

When she returned, they had both vanished.

A Fragile Future

Migrants who are suspected to be victims of human trafficking are primarily supported by IOM protection teams, which coordinate across a broad network of police, other UN agencies, NGOs, migrant-led advocacy groups, and government-funded social services.

UN staff play a vital role in this support system, says Pereira. “[Migrants] feel much more at ease with individuals who are there solely to offer support,” he explains, noting that many fear approaching police due to concerns about retaliation from traffickers or public exposure of their stories.

World Day Against Trafficking in Persons (July 30) encourages communities to advocate for action against trafficking in concert with the Blue Heart Campaign, an awareness initiative launched by the UNODC. But this year, IOM is trying to determine its future role in the fight against trafficking in Roraima. Since the U.S. funding cuts in January, it tried to sustain its operations. But U.S. rescission bill, signed by President Trump on July 24, resulted in permanent losses. IOM is now working with the Brazilian government to gradually reduce its services while protecting vulnerable populations.

R4V reports $2.38 million is needed for human trafficking and smuggling response programs in Brazil. Of this, $272,000 is needed for the human trafficking response in Roraima alone.

The Legislative Assembly of Roraima is leading this year’s Blue Heart Campaign, “Human Trafficking on Highway 174”—a reference to trafficking on the border between Venezuela and Brazil. The campaign has been educating migrants, taxi drivers and others on how to recognize trafficking and help those trapped in it.

“The most important thing is not to lose hope,” says a Venezuelan volunteer working with Sister Gomes, “the message is to keep hope alive.”

*These names were changed to protect personal identification.

Julianna Deutscher, MD, MPH, is an emergency physician in Canada. In addition to her clinical work, she contributes to global health projects focusing on medical education, trauma program implementation, migrant and refugee health, and human trafficking prevention. Deutscher reported this article as a Johns Hopkins-Pulitzer Global Health Reporting fellow.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

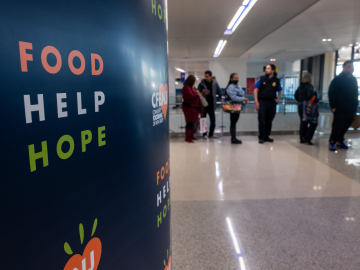

Downtown bus station in Boa Vista. A 2023 study published by Queen's University, in collaboration with IOM, found multiple reports of Venezuelan women and girls coming into contact with traffickers while waiting or sleeping at bus stations in the city's capital. Image: Julianna Deutscher