Launching a Vaccine Trial During an Ebola Outbreak

Just four days after Uganda’s Ministry of Health announced a new Ebola outbreak on Jan. 30, 2025, a team of local and international investigators began a trial of a vaccine candidate against the Sudan virus.

The remarkable speed in launching a clinical trial amid an outbreak reflected deep planning and pre-positioned resources, according to Swati Gupta, DrPH, MPH, vice president and head of Emerging Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology, for IAVI, a nonprofit that develops vaccines.

There is currently no licensed vaccine for Sudan virus, which causes severe hemorrhagic fever disease and has an average case fatality rate of up to 50%. Existing vaccines against the Ebola Zaire virus are not effective against Sudan virus.

The trial of IAVI’s VSV Sudan vaccine is being conducted by investigators from Makerere University and the Uganda Virus Research Institute, with support from WHO, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), and others.

In an interview with GHN, Gupta shares details of the trial’s quick launch and the ring vaccination strategy behind it.

How was the trial so quickly?

It's definitely one of the better examples of getting a research protocol started in the midst of an outbreak.

Part of the reason that we could get the trial started so quickly is because there was already Sudan virus vaccine in country, and the WHO also had pre-approved protocols and other documentation. We had worked hard to put those in place to make sure that, should an outbreak occur, things could move as quickly as possible and that we still have all the relevant approvals from ethics committees and the local government.

This was set up in preparation for an outbreak of Sudan virus, and you had everything in place and ready to go once an outbreak was declared?

Exactly, exactly. It's a large effort from the WHO. They are the ones that are implementing the protocol in country. It's really a partnership between the WHO, IAVI, CEPI, and, of course, all the people doing the hard work on the ground and the local investigators who are actually running the trial.

They are using the ring vaccination strategy. How does that work?

When a case of Sudan virus disease is diagnosed, a team of social mobilization experts go to the community where the case occurred, and they seek consent for that trial team to approach the community. After obtaining that consent, they identify all the people who had contact with that case within the previous 21 days. This forms the ring. Then they will basically randomize those rings, either to an immediate vaccination or to a vaccination 21 days later. That's why it's called a ring vaccination study.

It's basically a cluster randomized trial designed to look at the effect of our single dose vaccine to protect contacts of newly confirmed cases. So, they're looking to see if the vaccine can protect against laboratory confirmed Sudan virus disease.

How many rings are there in this trial? How many people are being vaccinated?

The WHO announced nine rings this morning [Feb. 13], and we are awaiting further updates from the WHO team. They will develop rings based on the number of cases they see. We're awaiting more information as they get into the field and speak with the local elders within the communities to get permission to have the teams come in.

Given this situation, it doesn't sound like this would be like huge numbers of people vaccinated. Will the trial be large enough to prove the vaccine’s efficacy?

Ultimately it will come down to the number of rings, attack rate, and the size of those rings to determine if we can show efficacy statistically. Hopefully, we are able to show the group that's vaccinated immediately has fewer cases or no cases. We won't know that until we better understand how large the outbreak ultimately ends up being.

When do you think results may be ready from this trial?

They're just getting started, so it's a little bit early to know the answer to that question. There are outbreaks which, fortunately are contained right away, and you don't see very many cases. In which case, you may not be able to show efficacy of the vaccine because there weren't enough people enrolled. If the outbreak continues, we'll be able to tell if there's more of a chance of showing efficacy.

There's a huge focus right now in the global health community on changes in U.S. government funding and policies. Have those had any effect on this trial or other work by IAVI?

We are definitely affected by some of the changes that are occurring in terms of funding. We're waiting to see how things evolve. It has also made communication more challenging—you have certain groups, for example, that can't communicate with WHO. But there's a large group of people that are working as hard as they possibly can to come together and contain the outbreak as we normally would.

Ed. Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

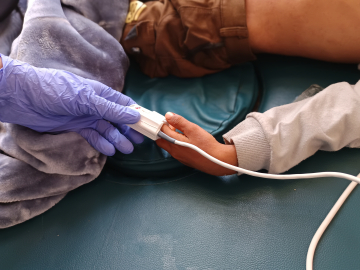

Health workers prepare the launch of the Ebola vaccination campaign at Mulago National Referral Hospital, in Kampala, Uganda, on Feb. 3, 2025. Hajarah Nalwadda/Xinhua via Getty