‘Heat Poverty’: A Growing Threat in India

NEW DELHI—Increasingly extreme heatwaves are forcing India’s most impoverished people into heat poverty as they borrow large sums to buy air conditioners for their homes.

The air conditioners may make life bearable as temperatures have reached as high as 52°C (126°F) this year, but they are sharply increasing personal debt while exacerbating the “urban heat island” effect in crowded cities.

Sitting on the concrete floor in her air-conditioned one-room house in a densely populated west Delhi slum, Maya Devi worries about her husband and children who have to step out every day in the scorching heat to go to work or school.

Devi works as a maid for a middle-class family and earns only US$50 per month, bringing the family’s monthly income to about US$120. After enduring several summers of extreme heat, she borrowed US$215 from her son’s employer last year to buy a second-hand air-conditioner. She wanted to avoid another round of annual heat-related nausea, headaches, and dehydration among her children.

"We are a family of five living in a 6-foot by 4-foot room [1.8 by 1.2 meters]," says Devi, explaining that some family members sleep outdoors on the roof of their room or on the street on a charpoy (woven cot). “Some nights, we would all stay awake because the heat was unbearable, and humidity from the small water-run cooler would make it difficult to breathe. My three sons missed school [or] work several times after falling ill due to the heat, thus losing several days’ worth of daily wages. That’s why we decided to take a loan.”

The employer now deducts US$15 per month from her son’s already low salary, pushing the family more into debt.

But despite the loan and debt, Devi and her husband, Om Prakash, a rickshaw puller, are relieved that unlike previous years, they did not have to miss work—or face heat exhaustion like their neighbors.

“Our next-door neighbor, a construction worker, has not returned to work in a week,” says Prakash, on a broiling afternoon in early June. “The family stays up most nights due to unbearable heat, and he worked hard during the day. It all took a toll on him.”

Prakash returns home from his rickshaw work in peak afternoons to rest in his air-conditioned room. However, to avoid further debt in electricity bills, he only runs the air conditioner for a half hour during the day and about an hour at night.

Of the 800-odd shanties in the slum that mostly house daily wage workers, Prakash estimates that 150 now have air conditioners—all bought on loan or consumer credit schemes. This alone is leading to heat poverty—a now-common term in India. They take loans at a high interest rate (up to 15%) or miss day wages due to extreme heat, leading them to further poverty.

The need for air conditioners is only increasing in Delhi, a metro area of about 33 million people, because of the "urban heat island" effect. Dominated by concrete, brick, steel, and asphalt, the city has minimal tree cover, effectively soaking up and retaining heat, says Ritika Kapoor, a climate scientist at Natural Resources Defense Council India.

The reduction in green areas and changes in land use combined with the proliferation of air conditioners that expel hot air into congested and poorly ventilated spaces are causing temperatures to surge up to 6°C higher than the city's average, says Kapoor, leading to health issues, increased energy consumption, and diminished quality of life.

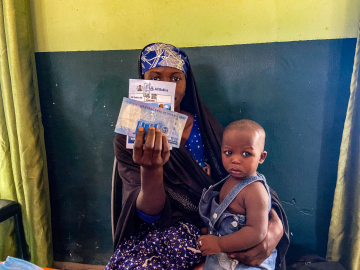

Maya Devi borrowed US$215 to buy an air conditioner after suffering New Delhi’s extreme summer heat for years. June 2, 2024. Cheena Kapoor

Worsening Heatwaves

Record-breaking heat waves in the last two years have put 90% of people in India at increased risk of income loss, poor crop yields, and vector-borne disease, according to a PLOS Climate study published last year.

“Long-term projections indicate that Indian heatwaves could cross the survivability limit for a healthy human resting in the shade by 2050,” the study authors write. “Moreover, they will impact the labour productivity, economic growth, and quality of life of around 310–480 million people.”

During India’s record-breaking heat wave between March and June this year, at least 100 people died, and 40,000 suffered heat stroke—more than 19,000 of them in May alone as the temperature soared to a national record high of 52.3°C (126°F).

An estimated 730 people in India died from heat stroke in 2022, per the Ministry of Home Affairs’ National Crime Records Bureau in India—almost double the number who died in 2021.

“I have not seen such overwhelming numbers in my over two-decade career,” says Ajay Chauhan, head of Internal Medicine at Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital in Delhi.

The government-run, tertiary-care hospital recorded 20 heat stroke cases and two deaths in a single week in May, says Chauhan, who helped draft national heatwave guidelines. “Until a couple of years ago, we used to get heat exhaustion cases, but rarely heat stroke cases,” he says. “However, things have changed recently.”

In the past year, Chauhan has trained 2,000+ doctors in person and online across India in managing heat stroke. He also helped set up the country's first heat stroke unit with ice-making machines and inflatable tubs for rapid treatment.

Chauhan notes that most of those who are brought [in] for treatment are men ages 30–50 who work outdoors: “We hardly get any women patients, which shows that the lower income group men, who work as laborers, rickshaw pullers, are more at risk of getting a heat stroke,” he says.

Kapoor notes the risks of heat-related illnesses to other vulnerable groups, including children, the elderly, and people who live with chronic disease. The risks will only grow as “climate change fuels longer, more frequent, and more intense heat episodes,” says Kapoor. “Thus interventions and vulnerability assessments are much needed to build climate resilience.”

Paying Off the Debt

Extreme heat is not only causing severe health problems in India. It’s also increasing the poverty gap. Rising temperatures could cost India 2.8% of its GDP by 2050, per a 2018 World Bank report. By 2100, that number could fall anywhere from 3% to 10%, if adequate mitigation policies are not instituted, according to a 2022–2023 Reserve Bank of India report.

The frequency and intensity of heat are increasing each year, leading to desperation among people trying to access cooling solutions. Air conditioner sales are soaring—especially in Delhi.

The market for air conditioners is estimated to grow to US$5 billion by 2028. A majority of new air conditioners are bought on equated monthly installments that pay off loans within a given time period or other credit schemes. The high number of personal loans since last year forced the Reserve Bank of India to caution lenders.

“It is a vicious cycle, either we avoid loans, suffer in heat and miss work, or we take loans, stay healthy and work to pay off the debt,” says Devi.

Cheena Kapoor is an independent journalist and documentary photographer based in Delhi.

Ed. Note: This article is part of Global Health NOW’s Local Reporting Initiative, made possible through the generous support of loyal GHN readers.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

A man takes rest from selling water bottles on a hot afternoon near India Gate in Delhi. Cheena Kapoor