Movement to Phase-Out Mercury in Dental Fillings Notches a Win

LONDON and LUSAKA—The use of mercury, a key ingredient in dental fillings for over 150 years and a potent source of environmental pollution, will be phased out worldwide by 2034 following a landmark agreement reached at COP6 in November.

The 153 parties to the Minamata Convention on Mercury approved the decision during COP6 in Geneva in early November. While some 50 countries, including all EU member states, have already phased out dental amalgam—a material made of liquid mercury and silver—many others, including the U.S., still allow it, despite concerns over mercury’s potential health risks and its harmful impact on the environment.

But late endorsements from key players, including the U.S., Brazil, and the WHO, helped secure the agreement. U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr., an environmental lawyer, reversed the U.S.’ long-held position on mercury.

“Why do we call it dangerous in batteries, over-the-counter medications, and makeup—but acceptable in vaccines and dental fillings?” he asked in a video address at COP6’s opening on November 3.

Mercury from dental fillings primarily enters the environment through crematorium emissions, which release vaporized metal from amalgam fillings into the air—eventually settling on land or washing into rivers and oceans. The WHO has warned that just 0.6 grams of mercury—the average amount in a single filling—can pollute 100,000 liters of water, enough to fill a swimming pool, making it unsafe to drink, as GHN noted in a June article on Zambia’s efforts to ban mercury amalgam fillings.

A 2017 report estimated that mercury amalgam fillings had released 1,297 kilograms of mercury into Zambia’s environment.

“The decision has thrilled me and the dental fraternity,” says Gabriel Mpundu, MD, a dental surgeon and president of the Zambia Dental Association. “The environment will be safer when all mercury-based products have been fully eliminated.”

The COP6 agreement is an “historic decision,” says Florian Schulze, head of the European Network for Environmental Medicine, which tracks nations’ progress under the Minamata Convention. Along with the U.S. position change, he told GHN, pressure had been building, as “many countries had already proven that alternatives are effective, efficient and affordable.”

Some of the countries that had already banned mercury amalgam, for example, have embraced environmentally friendly alternatives such as composite resins and glass ionomer cements that some studies suggest are just as durable, and perhaps cheaper when factoring in the environmental cost.

The EU banned dental amalgam in January, and African countries including Tanzania, Uganda, and Gabon have successfully implemented bans, while Mozambique has banned its use in public programs. African countries have long spearheaded efforts to amend the Minamata Convention, Schulze noted, and aimed to set an even earlier deadline—2030—for phasing out mercury amalgam, arguing they lacked the facilities to safely manage mercury waste.

Britain, alongside Iran and India, opposed a phase out by 2030, saying it was too soon. The British Dental Association had previously argued that other materials were as easy to use or as long-lasting as mercury. The association estimated that it would take nine years to develop alternatives and implement prevention policies.

The Guardian reported in October that more than 98% of fish and mussels tested in English rivers and coastal waters contain mercury above safety limits proposed by the EU, citing analysis by the Rivers Trust and Wildlife Countryside Link.

Countries that have not yet phased out dental amalgam have to submit a progress report or a national phase out plan by December 31, 2027. Minamata Convention parties will also collaborate to reduce the availability of cosmetics with mercury.

The new agreement also includes an exemption allowing dental practitioners to use amalgam “when its use is considered necessary based on the needs of the patient,” reflecting joint advocacy by the FDI World Dental Federation (FDI) and the International Association for Dental, Oral and Craniofacial Research (IADR).

At COP6, the decision to phase out dental amalgam was met with applause and standing ovations, capping years of debate with what many nations call a victory for both human health and the planet.

Ed. Note: This article is a follow-up to Zambia Drags Heels on Mercury Amalgam Ban, also by Kennedy Phiri and Freddie Clayton. The idea for the story came from Michael Musenga, an environmental health practitioner for the Children’s Environmental Health Foundation in Livingstone, Zambia. Musenga won an honorable mention for his entry, "Making Zambia a Dental Amalgam-Free Country" in the Untold Global Health Stories of contest, co-sponsored by Global Health NOW and the Consortium of Universities for Global Health.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

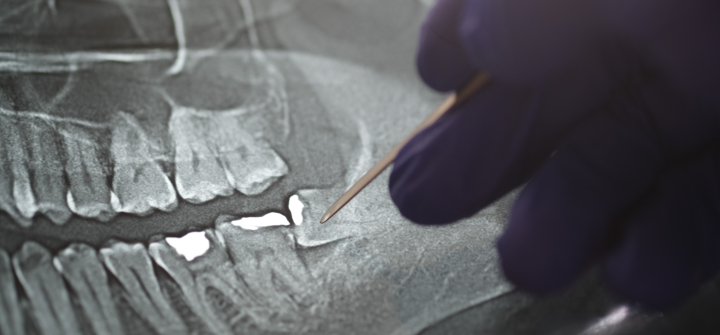

Panoramic Xray shows amalgam used for dental restorative material. Istock/Getty