The Push to Get Kenyan Cult Leaders to Embrace Modern Medicine

LUKHOKHWE, Kenya—On a cool Thursday afternoon in a village in Bungoma County, near the Ugandan border, Eliud Wekesa strides out of his modern house. Majestic and tall, he’s ready to speak to visitors in his compound about his journey in Christianity and the controversies surrounding it.

Clad in a purple cloak and black rubber sandals made from old car tires, he sits down in a shed on a wooden chair and pulls out his Bible before greeting his visitors. The 43-year-old father of eight is not new to controversy: He claims to be Jesus and has hundreds who listen closely to his teachings, including those about health.

Wekesa is only one of many religious and cult leaders, not only in Kenya but across the region, feeding followers a flawed gospel that dissuades them from seeking medical care when they are sick—claiming that only prayers can heal them. But health officials in Kenya (with police backing, at times) are working to dispel these messages.

Wekesa himself has run afoul of the law for his teachings; he’s been arrested several times. In 2011, police showed up in his compound in four SUVs and charged him with discouraging people from seeking medical care and preventing their children from going to school. He was held in a Bungoma police cell for 16 days.

His latest arrest, in May 2023, followed news of mass graves in Kilifi County, linked to Paul Mackenzie—the leader of one of the biggest cults in Kenya’s history who asked his followers to starve to death, telling them that they would then go to heaven. More than 400 bodies were exhumed, and 600 more people were reported missing. Most of the victims were children, reportedly denied school and medicine under the doctrines taught by Mackenzie, who was arrested and remains in police custody.

Police held Wekesa in custody for five days while they investigated whether his New Jerusalem church had any involvement; he was later released for lack of evidence.

There have been other examples recently of religious or cult leaders undermining health efforts in Kenya. Last December, police and area residents rescued four sickly children in Naivasha, a few kilometers west of Nairobi. They had been denied medication by the Church of God followers, according to residents of Maella village. Four other children reportedly died.

Wekesa, however, insists that he does not block his followers from health care. “I do not deny people the right to seek medication when they are sick. I even go to the hospital myself, take medication, and sleep under a treated mosquito net … because I asked God and he told me that this is an earthly body,” he says, gesturing to his arm.

Wekesa has also publicly modeled his acceptance of medical care. In 2021, the government launched a mass drug administration campaign to tackle two of Kenya’s most prevalent neglected tropical diseases (NTDs)—bilharzia and intestinal parasitic worms (including hookworm, ascaris, and whipworm)—in several western counties, including Bungoma. Wekesa took part, swallowing his drugs in public—raising hope that he would change his stance on medications and allow his followers to go to the hospital and take medicine.

But Dorcas Nafula, a community health promoter (CHP) in Namirembe (Wekesa’s village) says there is still resistance to medical interventions—especially from members of Wekesa’s church.

“Sometimes, during public vaccination campaigns, we go to the church immediately after the service to try and give vaccines, especially to the children. Once we arrive and the members see us at the gate ... they take off with their children,” Nafula says. “So, it keeps one wondering what he might have told them about the vaccines and medication in general.”

Wekesa’s wife, however, goes to the hospital or clinic whenever she is expecting a child, Nafula says—raising questions about why the cult leader preaches to his followers to do differently.

The influence of religious leaders urging their followers to shun medicine is one reason that many easily treatable health problems—including a number of NTDs—persist in Kenya and other parts of the world.

Simon and Eric Maloba smile as they chat outside their house in Ebulanda, Kenya, on February 28, 2024. Dominic Kirui

Eric Maloba, a father in neighboring Kakamega County, spent a year trying to help his 7-year-old son, Simon, after being told that someone had cast a spell on the child. “We spent a lot of money going to witchdoctors and pastors alike, before discovering what was ailing our son. He had to also skip a year of school; he could not go as he was always in very deep pain,” said the 36-year-old father of five.

Simon turned out to have very treatable intestinal worms (Ascaris lumbricoides). “After the surgery, he got well and is now a very happy kid,” Maloba said, holding his son in his arms.

Eric Maloba points at the scars on his son's stomach following surgery to remove intestinal worms in Ebulanda, Kenya, on February 28, 2024. Dominic Kirui

Edwin Ambasu, the head of Kakamega County’s Disease Surveillance and Response team, does not believe that religious leaders forbidding their followers from taking medicine has been a major problem in his county but feels it is a problem in other parts of Kenya.

“Some of the church leaders don’t buy into our ideologies nor agree to our strategies and interventions, and they hinder their followers and congregation from taking medication, telling them they will be healed in the name of Jesus,” Ambasu says.

He believes, however, that this is changing with the emergence of community health monitoring units and the involvement of religious leaders in government strategies—accompanied by training on the truth about medicine’s importance to human health.

“With the coming up with the CHPs and community health promotion strategies within the ministry, we are seeing that more and more people are being well educated and converted—they are actually taking the intervention,” Ambasu says. “If we continue with all these, some of these NTDs will be a thing of the past.”

Ed. Note: This article is part of Global Health NOW’s Local Reporting Initiative, made possible through the generous support of loyal GHN readers.

Dominic Kirui is a freelance journalist based in Nairobi, Kenya. He writes on gender, climate change, access to clean water, food security, culture, conflict, politics, and global development. Previously, he reported for GHN on life inside Laini Saba, a village within Kibera—the largest urban slum in Africa: As Population Climbs, Hygiene Suffers in Slums – March 23, 2022.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

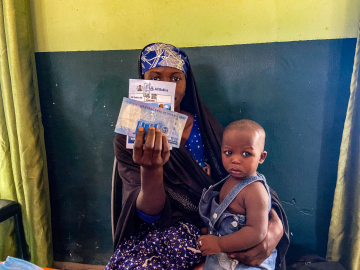

Eliud Wekesa speaks to visitors at his home and church compound in Tongaren, Bungoma County, Kenya, on February 29, 2024. Dominic Kirui