Why Leprosy Persists in India

MADURAI, India—Despite running one of the largest leprosy elimination programs in the world, India reported more than 100,000 new cases in 2019—more than half of the global total.

Why does leprosy persist in India? The reasons are myriad.

Back in 2005, the Indian government was optimistic about its success turning back the ancient disease. That year, the government announced that it had reached WHO’s target for elimination of the disease as a public health problem by bringing cases down to fewer than 1 per 10,000 people. However, the proclamation didn’t mean that leprosy—also known as Hansen’s disease—was eliminated altogether. Mycobacterium leprae, the bacterium that causes leprosy, was still being transmitted in the population.

Unfortunately, the government chose that moment to dial back its efforts. Once leprosy ceased to be a high-profile public health concern, the government stopped actively seeking out cases, frontline workers say. On the cusp of victory, it shifted attention and resources elsewhere—a familiar tale in global public health. The strict contact tracing for leprosy patients that had been a cornerstone of the country’s National Leprosy Eradication Program (NLEP) has slowed considerably, says Utpal Sengupta, PhD, a research scientist and a consultant at The Leprosy Mission India, the country’s largest NGO focused on leprosy relief.

That’s not the only reason M. leprae persists. Transmission of the bacterium is still poorly understood. Scientists believe prolonged contact with an infected person can lead to disease transmission via droplets expelled by coughing or sneezing. Better insights into transmission would likely yield better prevention and treatment options.

And resistance to anti-leprosy drugs has become a growing issue. In 1982, India began administering a 3-drug regimen of rifampicin, dapsone, and clofazimine to patients. (The WHO approved the MDT in 1984, but it would be more than a decade before leprosy-endemic countries would receive the treatment without cost.) It’s an arduous therapy, requiring a year of treatment for people with severe leprosy. However, if a patient doesn’t complete the medication regimen, it is possible for the bacterium to develop resistance to the treatment.

In 2018, to reduce transmission, the WHO initiated a single dose therapy (rifampicin) for the close social and household contacts of leprosy patients, but cases of rifampicin resistance have been recorded since 2009, says Sengupta, and this is being overlooked. “By the time you administer the single dose treatment, many contacts would already have the resistant bacilli, leading to more transmission and more cases,” he says.

Now, the country is facing new treatment complications: Some former patients who had multidrug therapy long ago are now facing relapses, while other patients are not responding to the regular drugs, Sengupta says. The Leprosy Mission India has identified 100+ such cases across India from 2019 to 2022. Half of them have developed drug resistance and are not responding to treatment or medication, he says, adding that studies are ongoing.

Faced with drug resistance, doctors can turn to other drugs such as clarithromycin, minocycline, and ofloxacin. However, by the time resistance is recognized in a patient, M. leprae may already have spread to others, Sengupta says, noting that drug resistance will pose a significant obstacle to India’s leprosy elimination goal if surveillance isn’t dramatically strengthened.

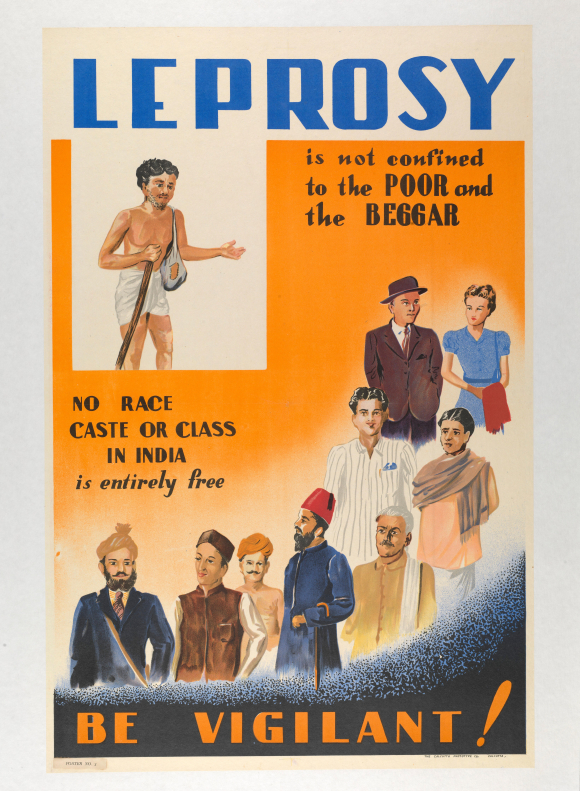

Another reason that India is still battling leprosy is stigma, which like the bacterium, persists with painful consequences. Disfigurement caused by the disease has long led to isolation and ostracism. Superstitions and rumors of being cursed traveled with the disease.

Color lithograph from the 1950s. Wellcome Collection

Venu Gopal Naidu, a founding member of the Association for Leprosy Affected People in India, knows well the effects of stigma. After he was diagnosed with leprosy in 1974, he was fired from his job as an accountant at a steel plant in the eastern Indian state of Odisha. “It was a miserable time,” he says. “No one can imagine the struggles and immense discrimination leprosy patients face every day.”

Fearing that his family who lived in the Southern Indian city of Visakhapatnam would also be socially isolated, Naidu moved 1,300 miles to Delhi and built a successful career as a financial consultant. Today, he volunteers at APAL as a social worker. His experience taught him a lesson. “Stigma leads to fear, with people trying to cover up the condition rather than treat it,” says Naidu.

Yet another obstacle preventing the disease’s elimination is that M. leprae exists not only in people but in the environment, according to a 2016 article in the Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprology, as well as a 2018 article by Sengupta. Clusters of cases are being detected near ponds used by communities for washing, bathing, and drinking. So, one solution for stemming leprosy cases may be to improve hygiene and sanitation, paying special attention to water sources. Contact tracing and closer surveillance of infections in communities should be done in the states like Orissa, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, and Chattisgarh—where leprosy has always been endemic and where the disease stubbornly persists, Sengupta says.

In the long-term, a vaccine remains the best solution, but that requires political will and the ability to overlook profit margins. In 2019, just before COVID-19 hit, India’s first leprosy vaccine, Mycobacterium indicus pranii, seemed set for a nationwide rollout. Developed by the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi in the 1970s, the vaccine has had proven efficacy since a 2005 field trial in Uttar Pradesh involving 24,000 people who were close contacts of others infected by leprosy were vaccinated with MIP. 68.6% were protected for 4 years, and 59% were protected up to 8 years. It was a modern milestone in the battle against an ancient disease.

However, since 2019, news of the leprosy vaccine has been scarce. A scientist who was part of the vaccine’s large-scale clinical trials but does not wish to be named says he isn’t aware of the vaccine’s fate since the pandemic began.

Market forces may be at least part of the problem. The vaccine is meant only for close contacts of leprosy patients, only those who are the most susceptible to the disease, so that limits its commercial potential, says Hariharan Periasamy, PhD, a scientist at the Drug Discovery Research Centre, Wockhardt Research Centre in Aurangabad, Maharashtra.

Without an assured market, pharma companies see a flimsy business case for investing their resources in discovery of drugs and development of new vaccines, especially since spending for innovative research is concentrated mainly in high-income nations where leprosy is not a public health issue.

“It is largely a disease of the poor,” Periasamy says.

Read part one of the series here.

Kamala Thiagarajan is a freelance journalist based in Madurai, Southern India.

Ed. Note: This article is part of Global Health NOW’s Local Reporting Initiative, made possible through the generous support of loyal GHN readers.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in over 170 countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

Custom-made microcellular rubber sandals are manufactured and given free of charge to patients at The Leprosy Mission Trust Hospital in Dayapuram, Manamadurai, for relief from foot ulcers and the management of leprosy-related disabilities. March 9, 2022. Kamala Thiagarajan