Africa’s vaccination effort is not losing steam. It is becoming more strategic.

Last month, a New York Times article detailed a loss of momentum for COVID-19 vaccination efforts in low-income countries, pointing out stagnating vaccination rates in many regions and calling the vaccination rate of Africa “most dismal.”

That’s a mischaracterization of recent strides that have improved equity and local vaccination rates.

Although the continent may fall short of the WHO’s 70% vaccination target for 2022, that doesn’t mean that the effort to turn the tide on low coverage should be abandoned. What’s needed instead is an integrated, sufficiently funded approach to generate demand and distribute vaccines—guided by real-time, hyper-local data.

For instance, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where less than 1% of the population of 89.5 million people have been vaccinated against COVID-19, efforts to reach the public at their place of need are actually becoming more data-driven and thoughtful—thereby yielding better results.

Vaccines sites—known locally as “vaccinodromes”—in Kinshasa province highlight how utilizing data can tailor the COVID-19 response to be more effective. In December 2021, the Ministry of Health’s Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) and VillageReach, a nonprofit seeking to transform health care delivery in Africa, opened a vaccinodrome capable of vaccinating 500 people each day in the Gombe municipality. Early demand proved the need for this site, with the Gombe vaccinodrome accounting for 18% of all vaccinations in Kinshasa between December 2021 and January 2022, the largest of any site in the province.

However, daily vaccinations at this site never crossed 150 people and began to fall significantly by February. If the government and site leadership had taken cues from the sentiments expressed in the Times article, the response would have been to cease operations completely. Instead, they took a closer look at the data: daily exit surveys showed that 35% of visitors were referred by a trusted community health worker. Another 20% were referred by personal networks, showing that word of mouth was a powerful demand generation tool in settings with high-vaccine ambivalence.

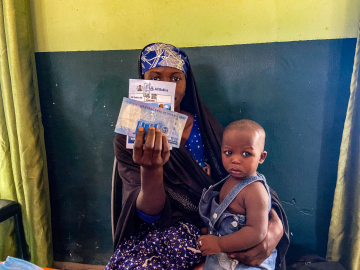

VillageReach and EPI responded with an immediate operational strategy pivot. They scaled down operations at the Gombe site and opened 3 additional smaller sites in other Kinshasa locations including a busy public square (Kalamu), a popular outdoor market (Masina), and next door to a large Catholic church (N’Djili). Simultaneously, more than 100 community health workers were trained to do community sensitization and provide referrals in the neighborhoods around the sites. Important details:

- The opening of these three new locations saw a 125% average weekly increase in vaccinations, often vaccinating more than 700 people a day.

- Remarkably, the 3 new sites were opened within just 18 days and operated on the funds originally set aside for the larger vaccinodrome at Gombe—proving that options exist to move with speed and efficiency if entities collaborate and make evidence-based changes.

- Leveraging community health workers is also central to building on this momentum: across all 4 sites, 50% of clients have been referred by CHWs.

Collectively, all 4 Kinshasa vaccinodromes have now vaccinated more than 37,000 people, and data indicate that momentum in favor of such community-centric vaccinodromes continues to build.

The Times piece points out that DRC also faces a surge in measles cases, seeming to argue COVID-19 is diverting resources from responding to this health emergency. However, this presents a false dichotomy: You wouldn’t ask a person in a high-income country to choose between receiving protection against COVID-19 or the measles, so why ask people living in low-income countries to do so?

Now is the time to innovate on the planning and delivery of all immunization services. The effort invested in building COVID-19 vaccine demand and distribution systems can inform other much-needed vaccine efforts as well. For instance, several Western governments provided specific guidance and resources to primary health providers to manage both pediatric vaccinations and COVID-19 vaccinations within 1 family visit. Data monitoring systems were set up to send regular reminders for getting a second dose and booster doses, and census data was used to predict upcoming supply needs. As seen from the experience in DRC, routine immunization services also need a comprehensive, locally resonant strategy that includes community representation and feedback.

With 17 million people living in Kinshasa, the work of the vaccinodromes is not losing steam; rather, it is just beginning, and becoming more strategic and adaptable by using data.

Vidya Sampath, MSPH, is director and lead of VillageReach’s COVID-19 Vaccine Delivery Program, working in 6 countries to support government vaccine rollout initiatives. She also served in a special secondment role at Public Health-Seattle & King County where she supported the design and set up of 6 COVID-19 medium and high-volume vaccination sites in 2021, leading to King County reaching 70% vaccination rates in just 5 months.

Ed. Note: Watch the Vaccinodromes of Kinshasa video here.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues:

A health worker at the N’djili vaccinodrome in Kinshasa administers a COVID-19 vaccine to a community member on April 11, 2022. Image: JNK Culture