A Faint Specter in Sierra Leone: Covid-19

FREETOWN, SIERRA LEONE —Travelers arriving at Sierra Leone’s Lungi International Airport enter queues that inch slowly towards eye scanners. Biometric data is captured, addresses and phone numbers are taken, and passengers shuffle towards rapid and PCR tests. They’re advised—but not required—to quarantine until they receive their PCR result (which rarely comes, since the center responsible for calling is only staffed by 2 people).

Then they’re free to go.

Once outside, it’s as if COVID-19 doesn’t exist. Along the airport road, groups of people eat and drink together, few wearing masks. Packed taxis and mini-buses run late into the night.

After Sierra Leone declared its first coronavirus case on March 31, 2020, President Julius Maada Bio announced a 1-year emergency—imposing a nighttime curfew, closing schools, markets, and international borders, and limiting hours for worship services, bars, and restaurants. For reasons that are still unclear—did the lockdown measures work? Or are infection rates in Sierra Leone lower?— the feared wave didn’t come. Fewer than 50 cases a day materialized for most of April through November 2020. Fearing economic and social instability from an extended lockdown, the government lifted restrictions. Kids went back to school, and borders, markets, restaurants and bars reopened. Infections spiked over Christmas and New Year’s, but that settled down quickly.

Relying on official government figures, which are hamstrung by limited testing, the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 dashboard map records 4,038 cumulative cases and 79 deaths.

The majority of the positive tests have been in the capital—particularly in the relatively cushy western part of Freetown. “We’re seeing cases concentrated in the more affluent areas,” says James Squire, MD, MIPH, MPhil, who heads the Ministry of Health and Sanitation’s National Disease Surveillance Program. “Basically, whoever has contact with the outside is more likely to test positive.”

But the emphasis here is on those who “test positive”—not necessarily those who are positive. With limited COVID-19 facilities—just 17 treatment centers in a country of over 7 million—and no routine testing, most cases are detected in international travelers. Squire points out that nearly half of all COVID-19 cases have been found in those who tested positive before they traveled, suggesting that there is potentially widespread community transmission that’s simply being picked up in this subgroup. For everyone else, limited access to—and low trust in—over-stretched, under-staffed facilities may dissuade testing, keeping official rates low artificially low.

To get a better sense of the true disease burden, the Africa CDC is partnering with the Ministry of Health and Sanitation and other African countries to conduct COVID-19 antibody surveys. Preliminary data suggests a significantly lower prevalence for Sierra Leone than Europe or America, Squire says.

Data aside, it certainly doesn’t feel like COVID-19 is the omnipresent worry it’s become elsewhere. Hospital wards aren’t filled with wheezing patients—there were 919 available beds across the country as of early April. People aren’t talking about lockdown stress or loved ones being fine one day and then unable to breathe the next. Squire does think that transmission rates are genuinely lower, given a less mobile population, few international travelers, low average life expectancy (54 years) with relatively few over-65s and no nursing homes, low rates of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, and lots of time outdoors—in open-air markets and airy restaurants, churches, and mosques.

But COVID-19 may also feel less tangible because the virus has so much competition. Sierra Leoneans regularly face serious health threats: malaria, typhoid, cholera, and some of the world’s highest maternal and child mortality rates. And then there’s neighboring Guinea’s Ebola outbreak. Morie Saffa, who worked as a hygienist in eastern Sierra Leone during West Africa’s 2013-2016 Ebola outbreak, says he’s not sure he gets all the fuss: “I’d take COVID over Ebola just about any day.”

Asked about COVID-19, most Sierra Leoneans reply with stories about everything surrounding the virus. A young father lost his hotel job when the guests dried up; he’s trying to work as a motorcycle driver, but his bike keeps breaking. A woman selling roast meat on the side of the road lost her lucrative selling spot in front of a private school during the lockdown.. Now in a less prime location, she makes maybe Le5,000 a day—about $0.50. She is pleased that reduced church service has given her more time with her kids. An NGO worker’s contract hangs in limbo because money from the UK is drying up. An importer explained how restrictions disrupted sugar and rice prices. A large bag of rice, enough to provide the most basic sustenance for a small family for a month, now costs Le340,000 ($34), double what it cost five years ago and about 60% of the minimum wage. 86% of respondents to an October 2020 Innovations for Poverty Action survey reported food insecurity during COVID-19.

Sierra Leone’s coronavirus measures are strikingly lax, but that doesn’t mean they should necessarily be strengthened and risk provoking even more severe economic and social strife for an already-struggling population.

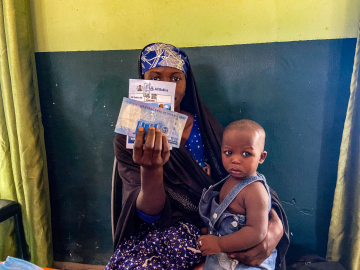

But the virus’s invisibility may hamper vaccination efforts. Sierra Leone has supplies of AstraZeneca and SinoPharm shots. By the end of March, nearly 32,000 people had received a first shot, and Squire insists that there isn’t vaccine reluctance with 80% of the respondents to the October IPA survey saying they would take the vaccine. And yet, one of Freetown’s main vaccination sites was nearly dead quiet the last week of March. Ibrahim Bah, a 42-year-old driver, said he was going to wait maybe 6 months to a year to get a vaccine, “to see how it goes.”

In early April, the city’s UN clinic had so many extra doses that it offered AstraZeneca to foreign NGO workers, regardless of age or position. Skepticism of China’s outsized role in Africa and reports linking the AstraZeneca vaccine to blood clots haven’t encouraged Sierra Leoneans to offer up their arms. Several people told me they’re waiting for access to the same vaccines available in America before considering a shot.

With official COVID-19 cases remaining at a steady, low hum by March 31, 2021 President Bio let the emergency declaration expire. By then, almost everything had returned to normal; the final change was the complete lifting of the curfew. For now, COVID-19 is mostly a faint specter in people’s lives.

Masks, still officially required in many buildings, are mostly seen wrapped around chins. The most strenuous mask enforcement happened on Easter Monday, with a police officer harassing unmasked taxi and motorcycle drivers at a roadblock on a bridge leading to Freetown’s sparkling Aberdeen Beach.

Just meters down the road, most masks came off again. A woman riding in the motorcycle taxi next to me peeled off her makeshift covering, fashioned out of a soft, black cap, and exhaled. “I’m tired.”

That fatigue—of the virus itself, and the spectacle of COVID-19 prevention measures—worries Squire. “We’re waiting for our third wave,” he said. “Did you see how many people were at the beach Easter weekend?”

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues

A young student wears a face mask on her first day back at her Freetown, Sierra Leone secondary school on October 5, 2020. Image: SAIDU BAH/AFP via Getty Images