Why It’s So Hard to Solve the Ventilator Shortage

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to expand, one thing has become clear: there aren’t enough ventilators to go around.

A recent report by the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security indicates that there are fewer than 175,000 ventilators available in the US. Yet James Lawler, MD, MPH, an infectious disease specialist and public health expert at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, has estimated that up to 1 million people in the US could require a ventilator before the pandemic ends.

Existing equipment manufacturers are ramping up supply, and companies such as GM, Ford, Tesla, and SpaceX are retooling to produce the machines as well. But manufacturing more ventilators quickly enough to meet demand could be difficult: The machines are complex and can take weeks to build.

In the meantime, some physicians are experimenting with hooking up more than one patient to a ventilator at the same time. Doctors at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center in Manhattan, for example, placed two patients on the same ventilator last week. And do-it-yourself ventilator designs have begun to circulate online.

But such solutions can be risky.

Richard Branson, a respiratory therapist and professor emeritus at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine who advised the NYP/CUIMC doctors, explains that the lungs of COVID-19 patients in acute respiratory distress—a condition in which the lungs lose flexibility and cannot properly absorb oxygen or eliminate C02—require the most sophisticated ventilators available.

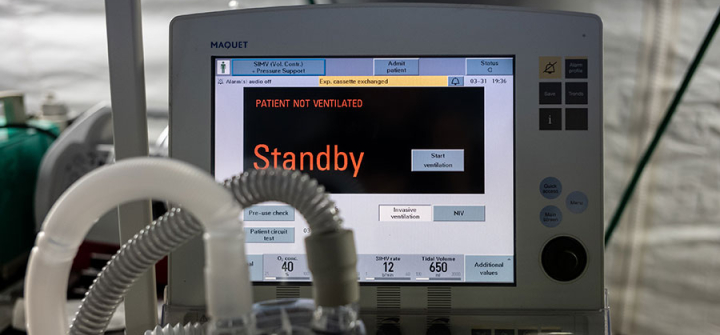

These devices precisely control the flow of air in and out of a patient’s lungs, and must be monitored and adjusted by a respiratory therapist, critical care consultant, or specialized nurse to make sure that the volume and pressure settings are correct for a given individual. They must also have built-in safety features and sound alarms in case of critical failure.

Using a single ventilator for multiple patients raises the risk of over- or underinflating any one patient’s lungs—with potentially disastrous consequences. “Think of a balloon that has never been blown up, and one that you have blown up 20 times, being hooked up to the same bifurcated straw,” says Lawler.

On March 26, several medical societies presented a joint statement discouraging the practice.

Simple DIY ventilators are unlikely to help the sickest patients, either.

“Just pushing good air in and bad air out is not a solution,” Branson says.

But Branson notes that not all critically ill patients will need a top-notch ventilator at the same time, and there may be enough to meet demand on any given day—if less ill patients could be put on simpler ventilators, and if the most sophisticated ventilators from hospitals with a surplus could be moved to those experiencing a crunch.

What’s more, a team of Johns Hopkins engineers recently prototyped a 3D-printed ventilator splitter that could address safety concerns around sharing ventilators among multiple patients.

Yet even if these hurdles can be overcome, others loom, including the lack of trained personnel to operate ventilators, as well as all the other resources required to care for critically ill patients. The Society for Critical Care Medicine estimates there are only enough properly trained personnel to care for approximately 135,000 ventilated patients.

“You have to have beds and IV pumps and drugs and, more importantly, ICU nurses and ICU respiratory therapists and pharmacists for those patients,” says Branson. “And all the ventilators in the world won’t solve that problem.”

A ventilator and other hospital equipment in an emergency field hospital to aid in the COVID-19 pandemic in Central Park on March 31, 2020 in New York. Image: Misha Friedman/Getty