The Myth about Herd Immunity

One common argument some parents make for declining vaccines for their children is that vaccines are not necessary—that their children are unlikely to get sick even if they are not vaccinated. Perversely, this argument relies in part on parents’ confidence that many other children are being vaccinated, creating “herd immunity” that makes it difficult for outbreaks to spread. In other words, if all my neighbors’ children get vaccines, my own unvaccinated children will benefit from the protection of the herd. But what happens if several neighbors also decline vaccines for their children?

Disturbingly, vaccine refusals are increasingly the reality in many parts of the US and elsewhere. In Europe, for instance, 90,000 cases of measles were reported in the first 6 months of 2019 alone. According to vaccination records of children entering kindergarten in the US last year, the number of parents seeking and receiving exemptions from required measles vaccinations increased to 2.5%, compared to 2.1% reported during the 2016-17 school year. As the US faces its worst measles outbreak in 20 years, these trends signal a dangerous lack of public understanding about how herd immunity works.

Typically, 93% to 95% of a population must be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity and prevent an outbreak of measles. Currently, the coverage rate in the US for the vaccine against measles in children 19–35 months is 90.4%, not even within that range. In 20 states, the vaccination rate is below 90%.

But even in states with rates above 93%, herd immunity offers no guarantees. The protective effect of herd immunity can vary based on the “herd” that an individual moves with. Relocation, travel or even a new circle of friends can change the composition of one’s herd, and thus its shared protection against infection.

Such a scenario unfolded in December 2015, when several thousand visitors to a California amusement park were exposed to measles. In total, 147 people were infected—most of whom were unvaccinated. In a scenario like this, where close contact with an infected individual occurs, the last line of defense is an individual’s own immunity to the disease.

It is troubling that public perceptions of susceptibility to measles have not shifted significantly since the measles outbreak in 2015-16, which was considered the worst in two decades. This year is expected to be even worse, with more than 1,200 cases recorded so far.

And there’s another reason to worry about potential measles outbreaks: New findings suggest that when children are infected with measles, the virus wipes out the protective effects of previous vaccinations against other diseases. This “immune amnesia” underscores the critical importance of measles vaccinations, which from 2000 to 2017 prevented more than 21 million deaths worldwide from measles alone. These new findings tell us that measles vaccines are likely preserving immunity against other infectious diseases as well—and that the true economic and public health costs of measles outbreaks may be much higher than previously estimated.

While vaccinations are often framed as an individual decision, these impacts on public health should not be undersold. Doctors and public health officials need to be more proactive in explaining these benefits.

A good place to start is by dispelling the myths about herd immunity—explaining to parents how herd immunity works, and when it doesn’t, and ensuring they understand the consequences to the larger community of the supposedly “individual” choice to forgo or delay immunizations. If we do this, we can help parents make better decisions that will benefit not only their own children’s health, but the health of all those with whom they come into contact.

Lavanya Vasudevan is an assistant professor of family medicine and community health, and global health at Duke University. Gavin Yamey is a professor of the practice of global health and public policy and director of Duke University’s Center for Policy Impact in Global Health.

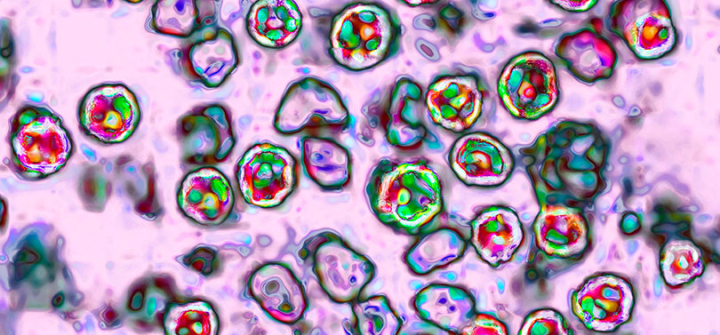

The measles virus, paramyxoviridae from the Morbillivirus family, transmission microscopy view. Image: BSIP/Universal Images Group via Getty