The Vaccine Story the World Needed to Hear

Journalist Cynthia Gorney could have written a piece about vaccine skepticism—what many westerners now think of when they hear the word vaccine. Instead, the University of California, Berkeley journalism professor chose to tell a story less told: how to get enough vaccines to kids who need them the most. Specifically, vaccines for pneumonia, which takes the lives of more young children than any other disease. And yet, the single biggest cause of fatal pneumonia in childhood is preventable with a vaccine. On the sidelines of #TropMed17, Gorney told GHN’s Dayna Kerecman Myers how Here’s Why Vaccines Are So Crucial, her story published in National Geographic late last month, unfolded.

What drew you to this story?

I knew that National Geographic wanted to do a significant piece on vaccines, and it was a field I’d love to learn more about. My specialty tends to be going into something cold and finding people to help me learn quickly—and that was the case here. My first big task was figuring out if National Geographic is going to spend many pages doing a vaccine story that matters, what should that story be for 2017? For those of us in the US, the knee-jerk reaction might be anti-vaxxers. But I felt that it has been done many times, and I sensed that internationally it was not the most important story to tell.

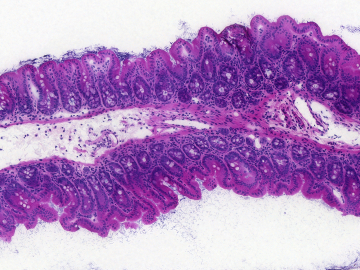

Through talking to people like Kate O’Brien, MD, MPH, [executive director of the International Vaccine Access Center at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health], I narrowed it down to several stories. I decided to tell the story of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PVC) and the effort to bring this relatively new, extremely costly vaccine to children in developing countries as an example of the biggest problem that I think faces vaccines today: How do we get enough vaccines to kids who most need them, because the consequences for them are most severe.

How did you settle on Bangladesh?

The reason I went to Bangladesh is very simple: Samir Saha, PhD [head of the Microbiology Department at the Dhaka Shishu Hospital and executive director of the Child Health Research Foundation in Bangladesh]. As a reporter, when I’m trying to find a way to tell a very complicated story, I look for marvelous guides: People who know the territory extremely well, who are physically appropriately situated to tell the story, and who are going to be wonderful to spend time with no matter how difficult or distressing the subject matter.

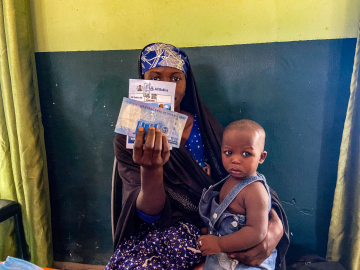

An American colleague pointed me to Saha, and after 15 minutes on a Skype conversation with him I knew he could be the center of this story. I told him, I’m going to be annoying and ask you a bunch of questions that you’ve explained to people a million times; I’m going to hang around hospital wards. Saha was ideal not just because of his research and ability to communicate it—he is also perfectly situated. His laboratory is right there—there’s the research. His team is going out and vaccinating people and studying people who have not been vaccinated; there’s that part. And the hospital is heavily populated by children who are there because they did not get adequate vaccine and therefore have contracted pneumonia and other infectious diseases, many related to pneumococcus.

Who do you most hope will read this story, and what do you hope they will take away?

When I write a story for a lay audience like National Geographic, people are coming to it with about the same level of knowledge that I have—which is to say they’re curious, but they have no particular expertise in this area. Neither I, nor any of my well-read, thoughtful friends in California where I live had any idea how many children around the world still die every year because of vaccine preventable disease. My primary task make people understand how serious an issue is in 2017 for literally millions of kids outside the developed world. Second, I wanted to convey how difficult the intersection of market capitalism and public health remains, and how problematic this is, in particular for vaccines that go to children in the developing world. Third, few people I encountered in the lay world knew what Gavi was. When I read about Gavi, that struck me as remarkable, given the vast amount of money involved, its work, and its international spread.

I wanted people to take away both the nature and scope of the problem, the failure of market capitalism to address this, and the large-scale efforts underway to try to do something about it. And to make it real. It was Samir’s brilliance, sending me to Rafia—a child who had not been vaccinated, who was permanently and terribly impaired because she had not been vaccinated—and who was alive.

Who surprised you the most—and who will haunt you the most, of the people you met and helped you tell this story?

That child is going to haunt me forever. Also, though, I was surprised by how much there was to be hopeful about. A non-Bangladeshi with a rudimentary knowledge of international vaccine efforts sees that situation and the immediate reaction is it’s terribly sad, but of course they didn’t get vaccinated—they’re too poor, it’s out of ignorance—I had to explain that none of these things are true. They have a much higher vaccination rate and much better awareness level than, I think it’s safe to say the US does right now. The clinic system is remarkably extensive. It was not that Rafia’s family did not have access to medication. It was much more profound and complicated than that.

Pneumococcus comes in multiple varieties. When the first versions of PCV were developed, they were not developed for the kids who needed them the most. They were developed for the kids who could pay for them. They were developed to address the strains of pneumococcus common in the United States, Canada, and the developed world.

Samir let the layers of irony of this situation build until it was clear: It wasn’t just that she couldn’t get it because she they were poor. Or that Bandgladesh couldn’t afford to buy it. It was that the vaccine that existed at that time wouldn’t have taken care of her anyway because it was designed for kids who didn’t need as much but could afford to buy it. It was so profoundly wrong.

I understand you cannot blow the profit motive out of the manufacture of medication or vaccines, but this struck me as a most obscene condensation of how this plays out. The ameliorating fact, of course, is that vaccines appropriate to kids of the developing world did begin to be made, not too long afterward, largely because of the intervention and enthusiastic distress of people like Dr. Keith Klugman [Director of Pneumonia at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation], who (along with Saha) will be at tonight’s event at ASTMH: The Live-Saving Vaccine the World Has Never Heard About. If you are not in Baltimore for ASTMH, you can still watch the event; it will be livestreamed here: https://www.facebook.com/StopPneumonia/.

Join the thousands of subscribers who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday enewsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues: Subscribe to GHN

(Editor’s note: