‘Music To Our Ears’: A New Malaria Treatment May Offer Long-Awaited Alternative to Artemisinin

It’s been more than two decades since the last major innovation in malaria treatment— artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs)—were introduced.

ACTs remain the gold standard, used to treat over 90% of malaria patients. But for decades, researchers have sought out a next-generation intervention that would reduce the world’s reliance on artemisinin. As with older antimalarials, they knew it was only a matter of time before the malaria parasite would acquire resistance to ACTs. Indeed, partial resistance to ACTs is believed to have emerged before 2001, and more recent findings in Southeast Asia and parts of Africa have increased the urgency.

Another option may now be on the horizon.

A new, non-artemisinin-based compound that combines a common treatment with a brand new technology has the potential to both treat malaria—including drug-resistant mutations—and block transmission of the disease, according to findings presented Tuesday at the at the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene annual meeting in Toronto.

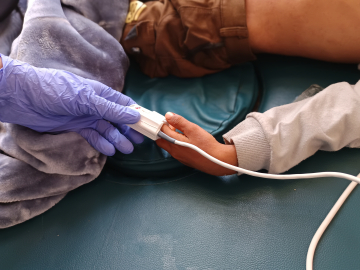

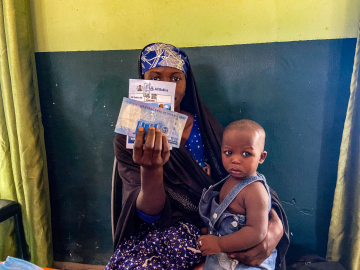

In the KALUMA Phase III study, the treatment, KLU156 (ganaplacide/lumefantrine)—known as GanLum—cured 99.2% of patients compared to 96.7% for the standard ACT treatments—and surpassed the WHO’s target cure rate of 95%. The trial studied 1,688 adults and children across 34 sites in 12 African countries, with GanLum given as a sachet of granules once a day for three days. Side effects like fever and anemia were comparable to standard treatments, but the treatment group experienced more vomiting right after taking the medicine, likely due to the medicine’s bitter taste—an issue researchers say they can solve.

Pending regulatory approval, the team behind the treatment—from Novartis and the Medicines for Malaria Venture—is hopeful that it “can be in the hands of patients within a year and a half,” George Jagoe, executive vice president, Access & Product Management, Medicines for Malaria Venture, said at a Tuesday press conference.

Malaria still kills 600,000 people every year—most of them children under 5 in Africa, and after years of decline, cases are on the rise.

The prospect of a safe and effective new treatment option will be “music to the ears of sub-Saharan African people who suffer from this terrible disease,” Abdoulaye Djimdé, a professor at Mali’s University of Sciences Techniques and Technologies and coordinator of the West African Network for Clinical Trials of Antimalarial Drugs, said at the briefing.

How It Works

GanLum attacks the malaria parasite on multiple fronts, combining a once-daily formulation of an existing antimalarial, lumefantrine, and a brand new intervention: ganaplacide, a novel compound said to attack the internal transport systems key to the parasite’s survival inside red blood cells.

When the malaria parasite enters the liver, it multiplies rapidly, then returns to the bloodstream—this is the asexual stage of the disease where symptoms like chills and fever arise. Like other antimalarials, GanLum targets this form of the parasite and treats disease.

But some malaria parasites move on to the sexual stage—gametocytes—where they can reproduce and be passed on to other hosts via mosquito bites.

“GanLum stops the parasite at this stage and helps block the transmission,” said Sujata Vaidyanathan, head of the global health development unit at Novartis.

GanLum’s origins reach back to the mid-aughts, when Novartis combed its library of 2.3 million molecules “to ask ‘which of these chemicals kill parasites.’ And that was the origin of this,” says Sean Prigge, a structural biologist and parasitologist who studies malaria parasites at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. He was not involved in the research.

Ganaplacide was one of the potential antimalarials identified in that massive screening effort at Novartis’ San Diego lab. From there, “it’s a big deal to get through a phase III trial, moving through safety and efficacy. It’s an exciting advance because it provides a long sought-after alternative to artemisinin-based drugs,” says Prigge.

Getting Ahead of Rising Resistance

Mutations in the Kelch13 gene of Plasmodium falciparum, the malaria-causing parasite, are leading to a rise in partial resistance to ACTs, which delays clearance of malaria parasites after treatment—in parts of Africa, raising concern for the nations hardest-hit by malaria, and questions about how new malaria drugs should be deployed.

Artemisinin partial resistance has been “spreading quite aggressively”—in the Horn of Africa, East Africa, and Southern Africa, says David Fidock, president of ASTMH and professor of microbiology & immunology and medical sciences at Columbia University, who was not involved in the research.

In Rwanda, Fidock noted, 40-50% of malaria parasites were found to have resistance to ACTs.

The Question of Access

Rather than holding these drugs in reserve—as is done with some antibiotics—they should be become a first-line treatment option in the most at-risk countries, Fidock said.

Even in countries where resistance is not a major issue, such as in West Africa, said Djimdé, GanLum could have a “front row seat” in the WHO’s effort to diversify the stable of malaria treatments to extend the life of available drugs, and head off resistance.

Prigge agrees that the drug will not replace ACTs but offer another option, with countries making their own decision about which drug to deploy based on whether ACT resistance is an issue in their region—and of course, cost.

Novartis says it’s “too early to talk about price” for GanLum but that, as with other antimalarials, the drugmaker is “committed to making sure that these medicines are made available on a nonprofit basis,” says Vaidyanathan.

How this plays out will dictate the drug’s impact, says William Moss, deputy director at the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute. “Key to [GanLum’s] widespread use will be its availability at low cost in malaria endemic countries”—where current treatments are priced well below $1.”

Further down the line, researchers hope GanLum—currently delivered over three days—can be developed into a single-dose cure. That ambition is “the holy grail, but it will take some time before we get there,” Djimdé said.

In the meantime, ACTs are still a frontline treatment that works well, but Jagoe is relieved to potentially “finally have a fire extinguisher ready” if K13 resistance “becomes the kind of crisis that similarly took down chloroquine and sulfadoxine pyrimethamine”—older monotherapy antimalarial drugs that, amid rising resistance, ACTs were designed to replace. “No one ever wants to be behind the eight ball again.”

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

GanLum product sachets and granules at Novartis manufacturing site in Slovenia. October 2024. Novartis