Early Warning Systems Vital for Climate Risk Preparedness in Kenya

KISUMU CITY, Kenya—While children run and play outside the tight cluster of three dozen white tents, most of their parents are searching for food. Some mothers are chatting before searching for clean drinking water not easily accessible in the camp.

The white tarp shelters, stamped with “IOM • OIM” and the UN’s migration agency’s logo, are crammed on perhaps an acre of land in southwestern Kenya’s Kisumu County. They house families displaced by last April’s floods.

Months after the deluge, three villages in Kisumu County—Nduru, Kadhiambo, and Ugwe—remain unlivable, and 1,000 families are still stuck in evacuation camps, according to Jeremiah Odongo, the area’s chief.

Serfine Achar, a camp resident, wishes to move back home, but says there’s nothing but mud left. “Floods swept away my home and I lost everything, including my livestock,” says Achar’s neighbor, Hellen Anyango, another flood victim and single mother of four. “My biggest fear is that the rainy season is here again.”

Camp residents Hellen Anyango (center) and Serfine Achar (left). Nduru camp, Kisumu City, Kenya. August 16, 2024. Scovian Lillian

Between last March and May, the floods left a trail of death, displacement, and disease across large swaths of the country—from the coastal areas to Nairobi and the Western Highlands. The floods killed 294 people, left 162 missing, and decimated 650,377 acres of farmland, according to the Kenya Red Cross. More than 30 cases of cholera were reported in Tana River County alone, per Save the Children.

The Kenya Meteorological Department had issued warnings about the onset of floods and the need for people to move to higher ground for safety—but people did not evacuate. They explained that the government’s lack of a proper plan, or any designated safe places or temporary housing they could move to, made it very hard for them to leave their homes.

Children at Nduru camp are often left alone during the day as their parents venture to look for food. Nduru camp, Kisumu City, Kenya. August 16, 2024. Scovian Lillian

Could lives have been saved during the flood and its aftermath if Kenya had a stronger early warning system, and health professionals were better prepared? The Milken Institute, which has been working since 2020 to help develop and improve early warning systems (EWS) for pandemic preparedness and health security, published a report last May that identified a significant gap in the integration of environmental factors into Kenya’s EWS and disease surveillance systems. By including meteorological data, especially during flooding, authorities can better anticipate outbreaks of waterborne diseases like cholera and vector-borne diseases like malaria, which have been exacerbated by this year’s floods, according to the WHO.

If health authorities can predict likely flood areas, they can preemptively distribute cholera kits, mosquito nets, and other disease-prevention resources to reduce the impact of potential outbreaks. Early warning weather indicators can also help with preemptive evacuations and public health advisories.

The report also noted financial constraints in Kenya’s current infectious disease prevention and treatment programs, which rely heavily on donor funding—funding that appears to have declined in recent years, undercutting early warning efforts.

Moreover, infrastructure and technology shortcomings—such as inadequate genomic sequencing equipment in laboratories, outdated health information systems, and limited access to computers and the Internet—hinder data collection and analysis in remote areas, making early warning more difficult. This shortfall, the report notes, underscores the urgent need for improvements in Kenya’s early warning infrastructure to inform on the health risks associated with climate-related events.

“In northern Kenya, for instance, droughts cause water scarcity, increasing the spread of diseases like cholera and dysentery. In the humid western and coastal regions, erratic rainfall and rising sea levels lead to frequent flooding, creating breeding grounds for malaria-carrying mosquitoes, which are health risks,” says Yun Fu, associate director of Innovative Finance at the Milken Institute and co-author of the report. And, the flooding’s destruction of latrines led to poor water and sanitation conditions in areas like the Mathare slums in Nairobi.

Collaborations between climate change scientists and health professionals are also essential, Fu adds. By sharing data and expertise, professionals can develop predictive models that accurately forecast health risks related to climate events, boosting preparedness and response times to health threats.

“Specifically, climate scientists can train health professionals to interpret and use climate data effectively and improve their ability to predict and manage health risks,” Fu says. “Investing in infrastructure such as weather monitoring stations and technologies for integrating satellite data into disease outbreak models is equally important.”

Trained health practitioners can prepare ahead of a storm by putting up mobile clinics that supply medicine to affected victims and enhance sanitation.

In Mozambique, for example, local community brigades trained to educate and alert communities about impending hazards caused by extreme weather events—a method embraced after Cyclone Freddy hit the country in February 2023. Since then, it has proven to be an effective and working early warning system method, according to the World Bank.

John Recha, PhD, a climate-smart research scientist at the International Livestock Research Institute in Nairobi, notes that EWS are crucial for timely alerts and information about impending climate change risks.

An aerial view of Nduru camp, near Kisimu City, Kenya, where 100 families have camped since April. August 16, 2024. Scovian Lillian

“Communities ought to be trained and educated on climate change risks responsiveness and safe evacuation procedures as well as managing climate change health threats,” Recha says, adding that both the national and county governments should collaborate to strategize better ways of handling floods to save lives in the future.

Recommendations for Kenya’s situation from the report and Fu include:

- Combining public and private sector capital to shore up labs, equipment, health information systems, and networks.

- Incorporating a broader range of non-health data, such as meteorological data.

- Training local health workers to detect early signs of health crises caused by flooding and respond swiftly.

Scovian Lillian is an independent journalist focused on science and health in Nairobi, Kenya. Her work has been published in Nature Africa, Talk Africa, SciDev.net, IJNET, The Continent, NPR, Mail and Guardian, and University World News.

Ed. Note: This article is part of Global Health NOW’s Local Reporting Initiative, made possible through the generous support of loyal GHN readers.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

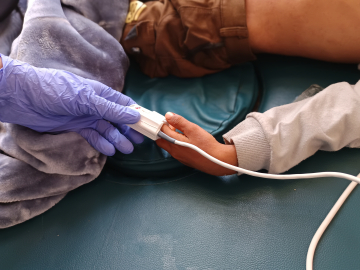

Hellen Anyango sorting a stash of firewood, which she occasionally sells to help support her four children. Nduru camp, Kisumu City, Kenya. August 16, 2024. Scovian Lillian