Cancer Care Inequities Are Costing Kids Their Lives

An estimated 400,000 children and adolescents worldwide develop cancer each year. But only half are ever diagnosed—and where a child lives can determine whether they survive that diagnosis. More than 80% of children with cancer in high-income countries are cured, compared to less than 30% in many LMICs, according to the WHO. What’s the reason for this massive disparity?

“The standard of childhood cancer care found in wealthier nations—precise diagnosis, complex treatment regimens, and physical and psychological support—is inaccessible for many children in LMICs,” says Andrew Kung, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Pediatrics at Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK).

That disparity inspired the SNF Global Pediatric Cancer Program, an initiative from the MSK Cancer Center and the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF) that “aims to improve outcomes for pediatric cancer patients through international health care collaborations,” says Andreas Dracopoulos, co-president of SNF.

In a Q&A with GHN, Kung and Dracopoulos discuss the global state of pediatric cancer, and what solutions are necessary to improve it.

What inequities exist in pediatric cancer care between LMICs and high-income countries?

AK: Unfortunately, inequities exist even at the point of initial diagnosis. Getting a precise diagnosis quickly is important, and this may be impeded by lack of access to state-of-the-art imaging and diagnostic testing. Access to drugs is also an issue that we are seeing globally—not just for new, high-cost drugs, but increasingly even for low-margin, generic drugs. A lack of high-volume centers—medical facilities that treat a large number of patients with a specific condition each year—may also impede access to specialized oncology, surgery, and radiotherapy expertise. Finally, inadequate supportive services may impact outcomes including quality of life, mental health, caregiver support, financial toxicity (problems a patient has related to the cost of medical care), education, and more. All of these barriers negatively impact survival rates.

AD: We’ve seen providers on the front lines of health care around the world working hard to support patients and their families, but many in LMICs simply don’t have access to the tools they need to provide the latest in research-backed medicine. Even as our scientific understanding of disease and treatment advances rapidly in certain areas, the resources to act on it, such as new diagnostic or imaging equipment, can remain prohibitively expensive in lower-income regions.

What is needed to lessen inequities in care and increase access to treatment?

AK: Each of the barriers to care and sources of inequity require a cross-disciplinary approach, often requiring private-public partnerships, governmental and non-governmental organizations’ participation, and regulatory and policy change, as well funding.

AD: Global collaboration is vital. When we work across borders and institutions, we can unlock a multiplier effect that helps lifesaving knowledge and expertise reach more people. From the beginning of our discussions with MSK Cancer Center, we were very happy to help establish opportunities for global collaboration with SNF’s existing Global Health Initiative partners: Sant Joan de Déu Barcelona Children’s Hospital, King Hussein Cancer Foundation and Center in Jordan, and Yorkshire Cancer Research in the U.K.

What is MSK’s SNF Global Pediatric Cancer Program proposing to do? And how will this improve patient outcomes?

AK: Through new collaborations and peer exchanges with hospitals and health care providers worldwide, we aim to optimize outcomes for young patients globally by expanding clinical care expertise, educational and specialized training, and collaborative translational research. Experts from MSK Cancer Center will also help facilitate patients’ access to primary diagnosis, treatment guidance, and state-of-the-art molecular testing.

AD: For example, the new program includes a visionary collaboration for the clinical development and future provision of pediatric cancer care at the SNF University Pediatric Hospital of Thessaloniki in Greece. The new hospital is slated for delivery to the Greek National Health System in late 2026, with the aim of enhancing access for children and families while introducing a new standard in clinical care and medical education in Northern Greece and Southeast Europe.

Can this model be scaled up to match the needs of LMICs?

AK: In an increasingly digital world, with capabilities to facilitate remote health care delivery, I believe that high-volume centers like MSK Cancer Center will increasingly be able to democratize access on a global scale. A commitment to knowledge transfer through training and education to increase local capabilities is also critical for scaling to global level.

What does the future of pediatric cancer care look like?

AK: There is every reason to be optimistic. Outcomes for many childhood cancers have advanced tremendously over the past few decades, forming a strong foundation to build upon. Ensuring equitable access on a global level is an imperative we share as a community.

AD: It’s not enough for excellent cancer care for kids to exist somewhere; it must be available everywhere. Our goal is to support health care providers in ensuring that a child with cancer from any part of the world has their best chance to survive, to live a full and thriving life. We can’t undo the heartbreak of childhood cancer, but we can contribute to making sure as many of the children who face it as possible have access to quality care.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share with friends and colleagues.

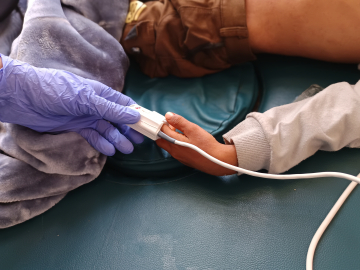

A boy who has cancer, sits on a bed as he receives treatment at the Oncology Centre in Sanaa, Yemen, on November 10, 2020. Hani Al-Ansi/picture alliance via Getty