Dear Medical Schools: You Can Still Seek Diversity Without Affirmative Action

In addition to studying, I—a Black third-year medical student—spent my first years of training pushing new initiatives and speaking out on the lackluster recruitment and retention of minority students at my medical school. These efforts were met with scapegoating, rationalizations, and ultimately inaction. Emotional fatigue forced me to take a step back from this work; I soon discovered language for the burnout that I, and other URiM—Underrepresented in Medicine—students have come to feel: the minority tax.

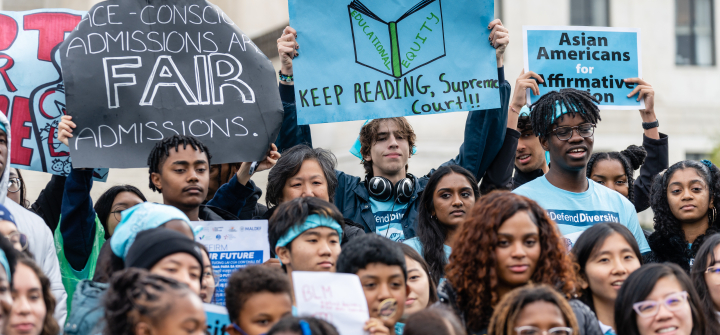

Then came the June 29 US Supreme Court ruling on affirmative action. The decision declared race-conscious admissions as unconstitutional for higher education institutions, reversing one of the nation’s few measures that seek systemic equity. While many institutions responded with statements promising to find other ways to promote diversity, others may use the decision to justify preserving their already predominately white institutions. I immediately thought of the repercussions on recruitment of URiM students, and how it will, in turn, reinforce dire health disparities for minorities in the US.

But as equity advocates have long known, affirmative action was far from a cure-all. The diversity of US physicians is abysmal. While the US population identifies as 13.4% Black/African American and 18.5% Latino, the population of doctors identifies as 5% and 5.8%, respectively. Meanwhile, first year US medical students identify as 11.3% Black/African American and 12.7% Latino, calling attention to the need for resources to retain URiM medical students.

Medical schools have a duty—and, frankly, an ethical responsibility—to produce a competent and diverse physician workforce. While affirmative action may have been a controversial policy, the benefits of diverse representation of medical students and physicians are well researched:

- White students who attended more diverse medical schools rate themselves as more prepared to provide care to minority patients.

- A more diverse student body and health care workforce encourages cross-cultural communication and improved, inclusive systems for patients.

- Bias-driven health disparities are better addressed with care from race-concordant providers who have improved communication, practice shared decision-making, and provide quality care.

- Patients who believe that their physician shares more insight into their culture or life experience are more likely to share health concerns and adhere to medical advice.

If medical schools value social justice and institutional equity, they must reaffirm their commitment to creating access for students from marginalized backgrounds. As Harvard University stated in response to the ruling, there are ways to “uphold the law, yet preserve essential values.” In the absence of affirmative action and race-conscious admissions, medical schools can:

- Ensure a holistic review for potential students, focusing on possible systemically-driven barriers like lack of mentorship—which thoughtful essay and interview questions can help capture in a way that test scores cannot.

- Prioritize recruitment efforts in specific zip codes, at Minority-Serving Institutions, and through community outreach programs that expose minority youth to medicine.

- Eliminate financial barriers in the application process that disproportionately impact URiM students—including de-emphasizing MCAT exam scores (proven to be linked more to wealth than medical school success) and providing travel reimbursements for interviews.

- Select a diverse admissions committee and mandate individualized training of all advisers, interviewers, and selection committee members to combat biases.

- Develop retention programming, such as tailored academic support to shield against the landmines of medical school that prevent many disadvantaged students from completing their studies.

This is more than a call to action—it’s a call to justice. Medical schools are integral to the nation’s health and must be socially accountable in dismantling, rather than perpetuating, systems of oppression. If medical schools are to give meaning to the words in their diversity statements or published commitments to anti-racism, they must prioritize achieving diversity in health care—outside of affirmative action regulations.

Diamanta Panford-Ufere is a medical student at Northeast Ohio Medical University and an MPH candidate at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Her interests include advocating for underserved communities, highlighting the culture of Black and Brown communities, and learning about effective public health strategies.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in 170+ countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues. https://www.globalhealthnow.org/subscribe

Demonstrators pose for a group photo during a rally in support affirmative action policies outside the US Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., October 31, 2022. Eric Lee/The Washington Post/Getty Images