India’s Mountains of Biomedical Waste

DELHI – Mohammad Hanif survived India’s long pandemic lockdowns by sorting through the waste dumped at one of the capital city’s biggest landfills and selling whatever he could.

Hanif, 38, lives next to the landfill known as Bhalswa in northwest Delhi. During the first lockdown in March 2020, he considered begging to feed his 3 children but survived on the meager earnings from selling used masks, plastics, and gloves after washing them in muddy water.

“Those were really hard times as we were barely surviving on the food or ration donations from the civil society,” he says, trudging through a mound of plastic bags and bottles in varied hues, pieces of cloth, and scraps of discolored surgical masks. He earns $1 per kilogram for the gloves or plastics he finds, selling them to a scrap dealer who, in turn, sells the waste for recycling.

Hanif and many of his neighbors turned to collecting BMW during the pandemic because gloves, masks, and other such plastic from hospitals were in high demand. Sanitation workers had little choice but to handle the massive amounts of waste generated by the country’s COVID-19 response.

A Pandemic-Era Stratum

As COVID-19 slowly loosens its grip on India, it leaves in its wake more than half a million deaths, damaged health infrastructure, financial duress, and mountains of discarded personal protective equipment.

Seen from a distance, the landfills look like craggy hills. When you get closer, however, you realize the hills are, in fact, towering mounds of waste. And the sound you hear is the cacophony of crows circling the peaks looking to scavenge. The next thing you notice is the smell of a city’s worth of decomposing garbage.

Delhi’s landfills alone hold massive amounts of waste: 8 million tons in Bhalswa, 5.5 million tons in Okhla, and 14 million tons in the Ghazipur landfill, which in 2019 had a waste mountain taller than the Taj Mahal.

And since the start of the pandemic, landfills have acquired a new top layer of biomedical waste, a pandemic-era stratum.

India has long lacked proper waste management, but the pandemic heightened need for investment in handling medical waste. During the pandemic, the country generated an average of 774 metric tons of BMW per day, much higher than the 619 metric tons in 2019. During peak days, daily BMW waste reached 1,614 tons, of which 60% was COVID-19 waste.

On May 31 of this year, in an effort to control waste generation from random testing, Delhi’s Disaster Management Authority issued an order that only government-accredited labs could test samples for the SARS-CoV-2 virus. While this reduced the use of home test kits, experts do not think it will solve the problem of immense amounts of biomedical waste across all major cities.

Waste Handling Risks

On March 18, 2020, India’s Central Pollution Control Board issued its first guidelines of the pandemic. It ordered all COVID-19 waste—even the waste that could potentially be processed and recycled—to be separated from regular waste and incinerated, says Satish Sinha of ToxicLinks, an environmental NGO.

This was bad news for people handling that waste, especially people like Hanif who scour the waste mountains for recyclable materials and other items of value from the landfills. Since even the recyclable waste was being incinerated, there was much less recyclable waste available to collect. And the waste that did reach the landfill was mixed, meaning the recyclable items had to be manually separated from BMW.

Ragpickers didn’t know the proper guidelines for handling such waste and put themselves at risk. Government sanitation workers say they, too, were clueless about the risks as the initial COVID-19 waves hit India.

Shamsher Kothi, a safai karamchari (sanitation worker) with the Delhi government, recalls becoming a frontline worker during the lockdowns and after, picking up COVID-19 waste from across the city for 2 and a half years with no time off. He’s angry at the government for putting him and his colleagues in a potentially life-threatening situation without any training or protective gear, or guidance in handling the contaminated waste. Kothi says he lost at least 52 colleagues in Delhi alone to the pandemic, though, of course, it’s impossible to say how they were infected.

SARS-CoV-2 is primarily transmitted via exposure to respiratory droplets, but it is possible for people to be infected through contact with contaminated surfaces or objects (fomites), according to the US CDC. The risk of such transmission most situations is relatively low. However, handling COVID-19 medical waste carries a greater risk. In its first guidelines, the Central Pollution Control Board ordered workers in BMW treatment facilities “be provided with adequate PPEs including three layer masks, splash proof aprons/gowns, nitrile gloves, gum boots, and safety goggles.”

However, the board didn’t specify guidelines for sanitation workers picking up household refuse containing SARS-CoV-2-contaminated waste.

Kothi and his 78,000 safai karamchari colleagues in Delhi worked without protective gear or even soap and water or sanitizer. “How would we know this waste had to be handled any differently than the regular household waste?” Kothi says. “We sanitation workers are at the bottom of society; whether we live or die does not matter to the government.”

The workers handled the color-coded bags (yellow for incineration and deep burial, red for chemical treatment, and so on) as general waste.

“None of my workers knew how to handle this infected waste,” says Sanjay Gehlot, chair of the Delhi government’s sanitation workers’ commission. “We raised several grievances with the government about this, but even till today there has been no concrete response.”

The workers continued to work without any safety gear or any other source of income because they had no choice, says Gehlot.

Elusive Compensation

The government announced a reparation of 1 crore ($122,294) to each family of those who died working the frontlines during the pandemic. But, of the 52 sanitation workers who died, only 3 families have received the compensation so far. The rest continue to chase officials with their documents in tow.

As the world starts to open up again, Hanif is back at work in Bhalswa. He has to pay off the $700 he borrowed from scrap dealers to make ends meet during the pandemic’s first year. He currently makes $6-$7 a day selling all kinds of waste, mostly biomedical, that he pulls from the dump.

Hanif, however, isn’t worried that he and the 1,000 other ragpickers in the area will die of COVID-19—they have long faced all kinds of pathogens.

“I have been scouting this mountain for 12 years now. There is nothing that my body has not already faced,” he says. “COVID-19 may or may not kill us, but hunger will.”

This story is part of Global Health NOW’s Local Reporting Initiative, made possible through the generous support of loyal GHN readers.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in over 170 countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

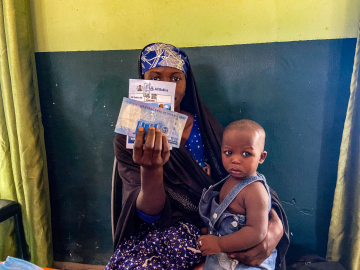

Mohammad Hanif washes recyclable materials pulled from the Bhalswa landfill in Delhi, on October 5, 2022. Image by Cheena Kapoor