As Heat Kills in India, Action Plans Save Lives

NEW DELHI – It is noon, and 65-year-old Habib Khan is sitting under a tree’s sparse shade looking worried. He’s facing yet another sweltering day with few customers.

In his 25 years of selling bananas in Noida, a satellite city 50 kilometers from Delhi, summers were never this harsh. Temperatures in the region soared much earlier than usual this year, leading to an exceptionally hot March, April and May. The extreme heat means fewer customers for his bananas, and Khan has to sit longer hours just to make ends meet.

“I have to sleep hungry often,” he says. “I am struggling to pay rent these days.”

Frequent power cuts at night makes it too hot for him to sleep. “If I sleep without the fan, I am covered in sweat,” he says. Recent research now shows that warming nighttime temperatures are eroding sleep globally especially in lower income countries.

And like 49% of Indian workers, Khan works outdoors in the extreme heat putting himself at risk.

High temperatures in summer reaching 40 to 45 degrees Celsius (104 to 113 degrees Fahrenheit) are not unusual during April and May in India. And heat waves can also hit during summer months. What has been unprecedented this year is the intensity and the duration of the heat waves (technically, any period when the maximum temperature is 4.5C to 6.4C [8F to 12F] higher than usual).

This March and April were India’s hottest months in 122 years of recorded history. In April, the average maximum temperature over Northwestern India was above 35.9C (97F), 3C (5F) higher than usual. In Pakistan, temperatures reached as high as 50C (122F). Rains, which usually offer a respite when the temperatures rise, have been missing this year in the Indian subcontinent’s northwest.

The result has been fires in forests as well as landfills, a 10%–35% decline in crop yields, and power and water shortages due to higher demand. Early reports have documented 90 deaths in India and Pakistan. However, only a small percentage of heat wave deaths typically get reported so the actual human toll is likely much higher.

How heat waves impact health

Heat waves are often called “silent killers” because unlike cyclones or other natural disasters like earthquakes, the impact is not always immediate or visible.

A rapid increase in heat compromises the body’s ability to regulate temperature and can speed death and illness in those who are already frail. The elderly, infants, pregnant women are more vulnerable to the heat wave, as are manual laborers and the poor, according to the WHO.

“When the temperatures rise beyond a certain level, the body cannot tolerate it and the cellular mechanisms start breaking down,” says Dileep Mavalankar, MD, MPH, director of the Indian Institute of Public Health in Gandhinagar, Gujarat.

Heat illness can begin with muscle cramps, dehydration and heat syncope (fainting), and progress through heat exhaustion and finally, heat stroke, which can prove fatal.

In a 2013 study, Mavalankar and his colleagues found that a deadly 2010 heat caused 1,344 deaths by comparing deaths during 5 consecutive summers in Ahmedabad Gujarat.

The study pushed the municipal authorities to act, and Ahmedabad became the first South Asian city to implement a “heat action plan.”

What can cities and states do?

Ahmedabad launched an early heat alert system, strengthened coordination between municipal departments like health, labor, power, and education, and enhanced the health system’s capacity to deal with heat-related emergencies.

Other steps included raising awareness about heat stroke via mass media campaigns, increasing water supply, creating cooling center shelters for those without electricity and homes, and limiting heavy work outdoors.

These measures helped save 1,190 lives annually in Ahmedabad, according to a 2018 evaluation. Encouraged by the results, 120+ Indian cities (including Delhi), and 20+ states have now enacted heat action plans.

Yet more needs to be done, says Abhiyant Tiwari, MPH, a heat health expert and member of Global Heat Health Information Network. “Heat waves are still not getting the desired attention and importance as other disasters like floods, cyclones or earthquakes,” says Tiwari. “Given the success of heat action plans by health and disaster management authorities in reducing mortality and morbidity, other sectors of the economy like agriculture, transport, and power should create their own heat action plans.”

Heat action plans also need to evolve and improve. Some experts have criticized India’s plans as focusing on responses rather than proactive measures. They also have noted that plans should take into account socioeconomic differences between communities.

Hotter, more frequent heat waves

The need for heat action plans and other measures will only become more acute in the coming years as human-led climate change will make these events more frequent and intense.

Climate change made this year’s devastating heat wave in India and Pakistan 30X more likely, according to a new World Weather Attribution initiative report. (A UK Meteorological Office report put the figure at 100X.)

“Global warming is supplying additional heat [to already hot summers] as increased carbon emissions trap more of the sun’s heat and change the way air and winds bring in moisture and heat,” says Roxy Mathew Koll, PhD, a climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology.

And high temperatures mean more air conditioners for cooling and groundwater pumping for irrigation, increasing electricity demand and emissions.

“Basically, the impact of this heatwave is on the food, water, and energy sector, and [it] derails us from the mitigation and adaptation strategy that we are currently on,” Koll says.

Swagata Yadavar is an independent journalist based in New Delhi reporting on gender, health, and the environment.

Ed. Note: This article is part of Global Health NOW’s Local Reporting Initiative, made possible through the generous support of loyal GHN readers.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in over 170 countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

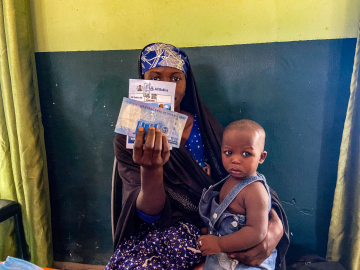

Extreme heat means few customers and little rest for Habib Khan, 65, a banana vendor outside Delhi. Image: Swagata Yadavar