Can Natural Farming Improve Farmers’ Health?

KANGRA, HIMACHAL PRADESH, INDIA—Babita Rana, 37, lives on a 3-acre farm nestled deep within the folds of the Himalayas in the village of Mundla in India’s northern Himachal Pradesh state. Until 2017, she suffered frequent spells of dizziness, nausea and vomiting. Nirmala Devi, her mother-in-law, had battled severe skin allergies.

Doctors told the women their ailments were caused by exposure to the synthetic pesticides, insecticides, and fertilizers they sprayed on their fields.

“I felt like we were poisoning our crops and bodies. We had to stop,” Rana says, sitting inside her modest house overlooking the fields and a cowshed. There are close to 93 million agricultural households—or nearly 150 million farmers—in India. And about two-third of them own small parcels like Rana's family, with close to 98% of all agriculture reliant on agrochemicals.

In 2017, the Ranas broke from the norm of using agrochemicals and switched to natural farming methods. They prepared homemade chemical-free fertilizers using cow dung, mulch and herbs to be sprayed on the fields. They also cultivated different crops on the same patch of land using an ecological and mixed farming approach. A few years later, their gamble paid off: After an initial setback in yield, the crops as well as the women’s health improved.

Babita Rana, a farmer, prepares homemade chemical-free fertilizers using cow dung, mulch and herbs to use on crops. Himachal Pradesh, India, October 27, 2021. Image: Mahima Jain

The International Labor Organization says agriculture workers run twice the risk of dying on the job as workers in other sectors. The WHO estimates that each year 2-5 million workers suffer pesticide poisoning, of which 40,000 are fatal. India’s media have covered headline-grabbing cases of the costs of pesticide use in recent years, including: the deaths of 50+ farmers due to accidental pesticide poisonings in Maharashtra in 2017, skin ailments and respiratory issues among tea garden workers in West Bengal, and high cancer rates in the agricultural belt in Punjab.

In response, a small but growing number of Indian farmers, often encouraged by government programs and farmers groups, are adopting natural cultivation methods. At the state level, Himachal Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, and Sikkim have launched natural farming programs. At the grassroots level, citizen groups like the Maharashtra Association of Pesticide Poisoned Persons (MAPPP) are advocating for ecologically sensitive cultivation models. Farmers like Rana believe natural farming will save their land, improve their health, and prevent occupational health hazards.

Highly Poisonous Pesticides In Use

Exposure to pesticides while mixing, storing, or spraying them can lead to health issues among farmers, explains Nikhil Srinivasapura Venkateshmurthy, MD, senior research scientist with the Public Health Foundation of India. Acute effects of pesticide exposure include sweating, frequent urination, itching, vomiting, or dizziness; whereas chronic effects manifest as diabetes or cancer.

Every year, an estimated 145 million farmers—nearly all of the population working in agriculture—suffer nonfatal unintended acute pesticide poisoning, estimates show. Nearly 7,402 people died due to “accidental intake of insecticides or pesticides” in 2021, government data show.

“Pesticide management in India is pathetic,” says Vineet Kumar, senior researcher at Sustainable Food Systems, Center for Science and Environment. “There is no one to show a farmer what pesticide to use for which crop. They make a cocktail of pesticides and spray it.”

The nonprofit Pesticide Action Network India (which facilitated the formation of MAPPP) has identified over 110 highly hazardous pesticides used in India. “Some of these are banned in the countries they are manufactured and exported from,” says Narasimha Reddy Donthi, PhD, a PAN advisor.

A Pitch For Natural Farming

Groups like PAN and MAPPP have been working to inform farmers about pesticides’ ill-effects and share alternative cultivation methods. A major benefit of the natural approach is that it saves the cost of pesticides, especially important in India where nearly half of Indian farmers are in debt, and tens of thousands have killed themselves because of debt.

The Andhra Pradesh Community-Managed Natural Farming (APCNF), a state program that started in 2016, not only promotes the low-cost model; it also explains how reduced pesticide use benefits farmers’ health. Nearly 750,000 farmers were practicing natural farming under APCNF by 2021.

In Himachal Pradesh, nearly 171,000 farmers, mostly women, have joined the state-run Prakritik Kheti Khushhal Kisan Yojana (PK3Y), which promotes natural farming, says Rakesh Kanwar, Agriculture Secretary for the state and project director of PK3Y.

“It is safe to assume that adoption of natural farming here is driven by women,” explains Kanwar. Women see and suffer the health hazards of chemicals and realize the importance of healthy and safe food, he adds. Research in other countries has shown that women farmers are more interested in environmentally friendly farming practices compared with male farmers.

Babita Rana inspects her family-run farm, which uses natural farming methods. Himachal Pradesh, India, October 27, 2021. Image: Mahima Jain

Rana says her family—and their land—are finally cured since the family stopped using agrochemicals. More than a dozen farmers in Himachal Pradesh shared similar experiences with this reporter.

“Can you imagine what was happening to us when we ate food grown with all those chemicals?” Rana says.

Not Everyone’s Convinced

In India, only 2% farmland, or around 2.78 million hectare (ha), was under organic cultivation in 2020. Demand for organic food is concentrated in urban areas.

“Sometimes pesticide use affects entire villages [making them sick]. But people are hesitant to move to natural farming. It’s not easy,” Donthi says. There are several social, economic and technical barriers to adoption of natural farming. For example, Rana has an octogenarian neighbor who suffers skin ailments caused by pesticide exposure but refuses to stop using the chemicals.

Rana hasn’t succeeded in convincing him. “He is afraid he’ll lose his crops, and the yield will drop,” she says.

His fears aren’t entirely misplaced.

Difficult Transitions

Experts warn that a sudden shift to natural farming can lead to low yields in the initial years. In Sri Lanka, agricultural output plummeted after synthetic agrochemicals were banned and a mandatory organic farming diktat was introduced in 2021.

Moreover, natural farming is labor intensive, the cost of which isn’t factored in by its proponents, Kumar says.

Rana and her family often can’t keep up with the demands of their agroecological farm growing mixed crops. During key sowing or harvest seasons, they rely on hired help. Rana also spends several days preparing farm inputs, but she says the extra work is worth it.

“At least the food I give my children is poison-free,” Rana says.

Mahima Jain is an independent journalist based in Bengaluru, India covering gender, health, and environment.

Ed. Note: This article is part of Global Health NOW’s Local Reporting Initiative, made possible through the generous support of loyal GHN readers.

Join the 50,000+ subscribers in over 170 countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

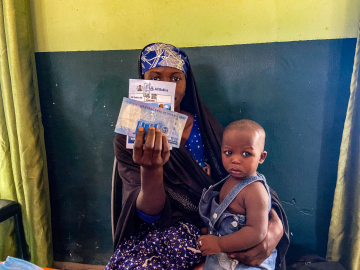

Veena Dhiman, a farmer-trainer from Nagrota Bagwan, with one of the indigenous cows she purchased to replace her jersey cows when she shifted to natural farming methods. Himachal Pradesh, India, October 27, 2021. Image: Mahima Jain