COVID-19’s Best Analog Is the 1930s Dust Bowl, Not the 1918 Flu

COVID-19 is a precedent-shattering monster of a pandemic. There’s never been anything quite like it.

Historians of public health have struggled mightily to find apt comparisons to our current pandemic. They’ve landed most often on the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918. On the surface, their reasoning makes sense: A lethal virus quickly spreads globally and infects millions.

However, the 1918 flu virus was not a new virus. Since 1900, only 2 novel viruses have caused global pandemics: HIV and SARS-CoV-2. Since HIV could incubate for years before causing clinical symptoms in its host, AIDS spread widely but unfolded slowly. SARS-CoV-2 uniquely combines rapid replication with high infectivity and lethality. This unholy trifecta has driven COVID-19’s widespread social and economic disruption.

Rather than drawing analogies to past infectious disease pandemics, historians should look to the 20th century’s great crises. For example, COVID-19’s open-ended shelter-in-place orders are reminiscent of those issued during the sustained, months-long air bombings of German, British, and Japanese civilians during World War II.

No pathogenic threat has ever packed quite the same 1-2 punch to America’s health and economic system as the coronavirus. The 1930s Dust Bowl during the Great Depression in the US comes closest, mimicking COVID-19’s acute respiratory distress and suddenness.

That disaster was caused by farmers using new technology to break the hardened soil of the Great Plains and open them to cash-crop agriculture. Severe, prolonged drought turned the soil to fine dust. Without the native prairie plants to keep it in place, the dust was sucked into “black blizzards”—massive, unpredictable windstorms that derailed trains, suffocated unlucky travelers, and infiltrated every crevice of homes and buildings. Half a million Americans were left homeless, and some 7,000 people, including many small children, died of dust pneumonia. Many others suffered lasting emotional trauma.

The Dust Bowl and the Great Depression lasted from 1929 to 1939 and were closely linked, according to environmental historian Donald Worster. Both events revealed American society’s “fundamental weaknesses” but also offered “a reason, and an opportunity, for substantial reform.”

Like the Dust Bowl, COVID-19 arrived with startling suddenness and penetrated every corner of our lives. The pandemic has goaded the US into reckoning with its failure to adequately fund agencies charged with national emergency response—a failure that has helped unleash the worst economic downturn since the Depression. The 2009–2010 influenza pandemic hospitalized roughly 250,000 and killed nearly 12,500 Americans, but between 2011 and 2018, Congress slashed the CDC’s public health preparedness and response programs by more than $8 billion. This funding drought, which also hit state and local health departments hard, made the public health infrastructure brittle and less responsive.

COVID-19’s greatest departure from the historical precedents of other pandemics has been Americans’ plummeting faith in the institutions charged with protecting the public good. According to Gallup, the percentage of survey respondents who expressed trust in Congress decreased by more than half from 1999 to 2019. At a time when we most desperately need unity and common sacrifice for the nation’s well-being, our public discourse is more antagonistic, and confidence in institutions more fragile, than at any time in modern US history. It’s no surprise, then, that the act of using a simple public health tool like a mask has become politicized.

Actions such as attacking the nation’s top infectious disease expert and robbing the CDC of its vital data responsibilities are uprooting the democratic and crisis-response ecosystems—much as the prairie sod was chewed up and spat out by steel-toothed, gasoline-powered tractors.

The COVID-19 pandemic will end, but how and when is still unknown.

The Dust Bowl finally subsided in 1939, after the rains returned, the soil stayed put, and farmers began practicing sustainable agriculture and planting trees.

Then, like the second wave of a pandemic, World War II hit an already exhausted nation. Wartime manufacturing and federal defense spending—10X that for the New Deal—finally ended the Depression. The war’s death and displacement also steeled the political will to build the fundamental framework of our national and global public health system: the US Public Health Service Act of 1944; the CDC, founded in 1946; and the WHO and the modern NIH, both founded in 1948.

Those steps may offer history’s most hopeful parallel: Out of the turmoil of our own times, we must reinvent public health on an even greater scale than the Greatest Generation did.

Karen Kruse Thomas is the historian of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. She is the author of Health and Humanity: A History of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 1935–1985 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

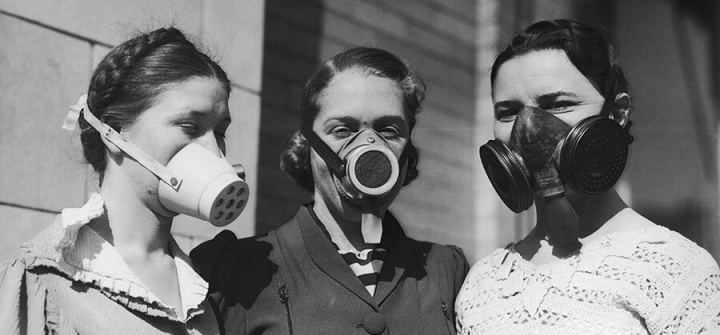

Young women model masks worn during America’s Dust Bowl disaster, circa 1935. Image: Bert Garai/Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty