Baltimore Protesters Weigh the Risks—and Take to the Streets

BALTIMORE—Face masks served double duty as mini protest signs Monday as over 1,000 people took over the streets of downtown Baltimore for a third straight day of protests against racial violence.

As helicopters circled in the afternoon sky, the youth-led march streamed past storefronts—boarded up in anticipation of the same violence and looting seen in other cities. Approaching City Hall, organizers halted the march to send a message:

“If you’re out here to cause problems please go home,” an organizer called through a megaphone. “This is a peaceful protest”—and save some tensions with police after dark, it remained so.

Protesters burned sage at Baltimore City Hall during a racial violence demonstration. June 1, 2020. Image: Annalies Winny for Global Health NOW

Protests following the death of George Floyd, the 46-year-old black man who died after a Minneapolis police officer knelt on his neck for over 8 minutes, have brought racial tensions to a boiling point across the US. Baltimore is no exception, but at Monday’s protest, the dominant feeling was that no one wanted a repeat of 2015, when a violent uprising and scores of protester arrests followed the in-custody death of another black man: Freddie Gray. With t-shirts and cardboard signs, marchers also paid homage to a laundry list of other names, from Tyrone West, killed in 2013 during a traffic stop with Baltimore police, to Breonna Taylor, who in March was shot dead in her home by Louisville police.

The string of protests across US cities—and now abroad—has no doubt seen social distancing take a back seat to social justice. But the possibility that racial violence protests could become COVID-19 super-spreader events—and the fact that COVID-19 disproportionately impacts people of color—was not lost on the sprawling crowd. Still, protesters in Baltimore made it clear that the COVID-19 pandemic does not override the need to address another public health emergency—racism—and many felt they had no choice but to tackle both head-on. Since Floyd's death, several medical associations have followed suit, releasing statements decrying racism as a public health issue.

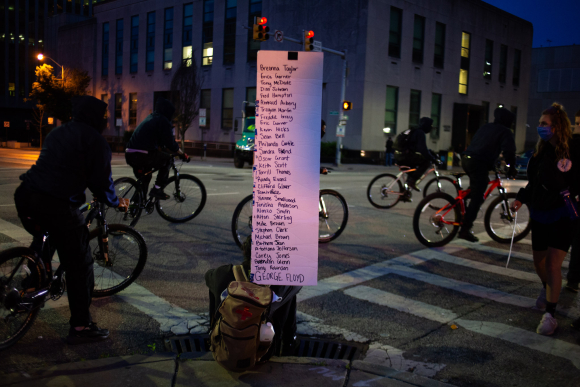

A protester sits on the curb outside Baltimore City Hall with a list of racial violence victims attached to his backpack. Image: Annalies Winny for Global Health NOW

Amid chants of “We can’t breathe” and “Black Lives Matter,” young marchers hauled communal coolers of bottled water, shared squeezes of hand sanitizer, and handed out the latest protest essential.

“Excuse me, do you need a mask?” Mimi, 21, asked a passerby (she declined to give a last name).

When they declined, another young woman shook her head and said: “It’s like some people out here want to get coronavirus.”

Coronavirus or not, protesting “is the reality of life,” for Mimi. She was just 18 months old when she went to her first protest, and 16 when Gray’s death sparked widespread unrest in Baltimore, says her mother, Terri Johnson. As a clinical social worker and the parent of 2 black children, Johnson sees the toll of racism and social inequities firsthand—and said there was no question that her family should attend the protest.

Racial injustice “infiltrates every part of who you are. If you don’t feel safe and you’re always in a hyper-vigilant state, how do you expect people to be healthy?” she asked, wearing a face mask with “Protect Our Babies” written across it.

Students from Morgan State University, a historically black institution, protest racial violence in Baltimore, Maryland. June 1, 2020. Image: Annalies Winny for Global Health NOW

As the protest made its way from City Hall onto I-83, which was partially blocked off for the event, a group of students from Morgan State University—a historically black institution in Baltimore—greeted each other by bumping forearms.

“We’ve been doing that since corona started instead of dapping each other up,” said Samuel Aribilola, 21, a senior attending his first protest.

When Aribilola told his parents he was going, they expressed equal concern about COVID-19 and the possibility of violence and police overreach. That same evening, peaceful protesters 40 miles away in Washington, DC were tear-gassed to clear the way for President Trump to visit a church near the White House. More than 10,000 people have been arrested in this latest wave of protests, according to an AP tally.

In Baltimore, the massive crowd paused as it passed the city correctional center, chanting messages of support to those inside. From behind the tightly slatted window bars, a chorus of amorphous voices replied: “Black Lives Matter! We love you!”

Protesters on I-83 march past Baltimore city jail. June 1. 2020. Image: Annalies Winny

“We know the risk we’re running by being out here. I originally had those fears that [COVID-19] might spread in a couple of weeks… But it was still no question for me,” said Joshua Adeyemi, 22, who lost an aunt to coronavirus.

Most of the time, he tries to block out the inherent danger of being a young black man in America. “I try not to think about how society really is so I can try to live my life. But when our fellow black community members are killed, it brings something out of us,” he says.

“I have been violated by a police officer. A black police officer,” added Brandon, 19, who did not give a last name. “I’m not saying all cops are bad, but certain cops need to step up and take initiative in their community.”

But when it comes to COVID-19, it’s on individuals to protect themselves: “We can all take some accountability while we’re out here,” Brandon says. “We understand we gotta have our mask on. There’s a lot of people, but we all can keep a certain amount of distance. We’re all out here to practice our First Amendment right.”

A young girl touches a painting of George Floyd inside a horse-drawn hearse. Image: Annalies Winny

As protesters gathered back at City Hall, prayer groups formed, the smell of burning sage filled the air, and weary demonstrators flopped on the grass and shared snacks, while others shouted at walls of masked police officers, some of whom took a knee in solidarity.

Across the street, Baltimore’s iconic Arabbers—urban horsemen known for selling produce via horse-and-cart—pulled up in a horse-drawn glass hearse loaded, in lieu of a coffin, with a painting of George Floyd by the local muralist Gaia. As the carriage pulled away for Floyd’s symbolic “last ride,” a young black girl—her plastic face protector resembling a tiny police shield—reached out to touch his painted face through the glass.

For the latest, most reliable COVID-19 insights from some of the world’s most respected global health experts, see Global Health NOW’s COVID-19 Expert Reality Check.

Join the tens of thousands of subscribers who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday enewsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues.

Baltimore's iconic Arabber horsemen protest with a horse-drawn hearse commemorating the death of George Floyd. June 1, 2020. Image: Annalies Winny for Global Health NOW