Precision Public Health and the “Luckiest” Dean

HOUSTON – Eric Boerwinkle isn’t your typical public health school dean.

He manages six campuses as dean and M. David Low Chair in Public Health at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) School of Public Health. The main campus in Houston is a 675-mile flight from the El Paso campus—roughly the distance from New York to Charleston, South Carolina.

And Boerwinkle, PhD, began his journey to the deanship in the laboratory—following a path from biology and biostatistics to human genetics and population health.

For the past 3 decades, his academic and research home has been the Texas Medical Center. Called the largest in the world, the medical complex has allowed him to make connections with health care and academic institutions, facilitating his passion for “precision prevention” by integrating genetics and genomics with population health science.

In an interview with GHN, Boerwinkle argues for closely connecting public health and health care and explains the role of genetics in precision prevention.

How do you lead a school that has 6 campuses? That’s got to be a challenge.

It actually is easier than it seems probably from the outside. I’d say the challenge isn’t really that we have 6 campuses—we’re 1 school—but the challenge and the opportunity is that Texas is a big state. When you fly from Houston to El Paso, you’re more than halfway to Los Angeles.

It’s no secret that Texas is a conservative state. Is public health a tough sell in a state like Texas? How do you work that with politicians?

Well, first of all, I would say Texas is known to be a conservative state, but Texas is also a shifting state. Politics in Texas has always been colorful. Whether it’s labeled as Democratic or Republican, you can bet that it’s colorful.

Cities like Houston and Austin are not as conservative as the state gets labeled on the outside. [And] even the most conservative politicians in Texas really understand the importance of health and health care, particularly … business conservatives. It’s important if you are a business person to have a healthy workforce.

BS: That sounds encouraging.

EB: Yeah, it’s usually not a warm and fluffy conversation, but it makes good business sense and … Texas cannot afford to have a population that has an extremely high rate of diabetes and organ damage. We’re not going to be able to treat and transplant our way out of it on the back end. We have to be able to prevent it on the front end. That’s not a hard sell.

What would you say has been your biggest challenge as dean of the school?

I would say my biggest challenge and the biggest opportunity is the ever-shifting landscape of health care. It’s very important that schools of public health think more about integrating mainstream public health into mainstream health care, form closer partnerships with medical schools and think about a continuum of health care that begins with early prevention on the front end.

Each 1 of our 6 campuses is attached to a medical school and a health care system. They’re also closely integrated with the health care system. We’re trying to move beyond traditional public health and think about public health, population health, and schools of public health in 2018 and beyond.

Is there one example of a collaboration that you have here at the Texas Medical Center that you would point to as ideal?

I’ve got to make sure I don’t get myself in trouble here [but] yeah, I would say it’s the partnership between myself and Richard Gibbs [of the Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center]. We’re 1 of the 4 national genome centers in the country funded by [the National Human Genome Research Institute] and 1 of 3 selected genome centers recently for the All of Us program.

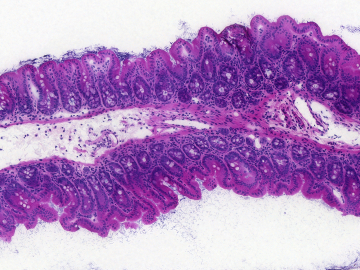

We’ve been able to advance the basic sciences of genomics and now we’re pushing … integration of genomics into health care. We’ve been very good in understanding basically pediatric genomics. [But] we realize that if we’re going to make an impact on health care, we need to shift into adult medicine and think about chronic disease and cancer. We’re doing that primarily in cardiovascular disease, developing targeted sequencing in cardiovascular disease to identify people at increased risk.

The ancestral diversity of Houston is extremely important because people move around, they bring their suitcases, but they also bring their genes. Because we have different histories, we have different genes. We’re very cognizant here of the need to tailor our genomics research again looking toward in the clinic to people’s unique ancestral history. That’s almost a unique view in the field right now.

I’ve been thinking about the incredible increase in knowledge and the technology around genomics and genetics. Is this shifting things more towards precision medicine and away from public health?

No. I think first it’s promoting ... I’ll call it, precision population health. I don’t think it’s a good idea to think about public health as separate from medicine and precision medicine.

I think it’s important that precision medicine or precision health care does not become health care for the rich. If that’s what happens, we will have failed. We have to have precision health and precision health care. It’s basically inclusive of all people. It’s incorporating and embracing all the diversity, including economic diversity.

It’s not competing with or separate from public health. Indeed, if we’re going to accomplish what I consider to be effective sustainable health care in this country, public health has to be an integral part of it.

It’s not a buzzword but it should be—think about precision prevention. There are prevention protocols that are going to work in some people and not in other people for a variety of reasons. Not just your genes. Your genes and your social circumstances. It’s not a one-size fits all in prevention.

It’s a challenge. The traditional power of public health has been one-size fits all, right? Vaccines or seat belts or things like that have saved huge numbers of lives. You’re talking about a massive shift. The price has come down for sequencing someone’s DNA, but it’s still expensive and then the treatments based on that would still be expensive. How do you get to that precision public health you’re talking about?

Yeah. You’re absolutely right. In fact, the traditional public health has been a single population-wide perspective. The view of public health going forward is not that one-size fits all for the entire population. We do [this] all the time, by the way, and we don’t talk about it. We tweak and modify literature, prevention programs to particular ethnic groups, males and females. We do it all the time.

What we’re going to be doing is … thinking about sustainable treatments for groups of individuals to better benefit them.

That can be done in a cost effective and sustainable way. I think it’s exciting as public health professionals that we’re at the table and we’re going to be pushing that perspective.

Do you feel fortunate in a way because you’re seeing your genetic research come together with public health?

Yeah. I’ll be extremely clear and tell you what I’ve probably told 1000 people: I’m the luckiest person in the world. I am the luckiest person in the world. I basically got good statistical training early and trained as a biologist [and integrated] that into collaborative population research. It’s basically bringing genetics to large population studies. It really is the ability to work very closely with population health scientists and study participants very early in the game to introduce genetics into population health.

You’re absolutely right. There’s luck involved and there’s standing on the shoulders and the infrastructure of people that came before me … good epidemiologists, biostatisticians, who had the foresight to bring into existence these large population studies.

Ed. Notes: This interviewed has been edited for clarity and length.

Brian Simpson is an alum of the University of Texas in Austin. Hook ’em, Horns!

Join the tens of thousands of subscribers who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday enewsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues: http://www.globalhealthnow.org/subscribe.html

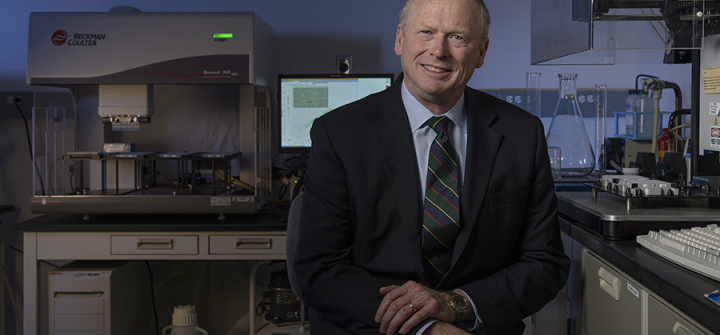

Dean Eric Boerwinkle has spent a career integrating genetics and population health science. (Image: Nash Baker / Courtesy)