Politicians, Philosophy and Other Leadership Challenges: A Q&A with Bill Foege

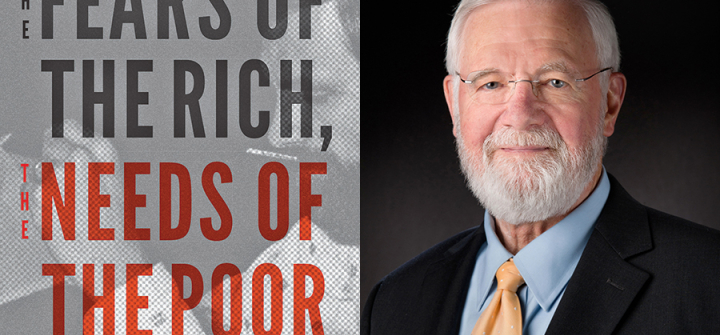

A pathbreaker in global health and a former CDC director, Bill Foege has some startling advice for young people interested in global health: Don’t have a life plan. “Life plans are an illusion,” he writes in his new book, “The Fears of the Rich, The Needs of the Poor.” Rather, he urges them to have a life philosophy that will guide them in the career and life decisions they make.

Foege, MD, MPH, is an emeritus professor at Emory University and an early consultant to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. He’s best known for devising the surveillance/containment strategy used to eradicate smallpox and for leading the CDC from 1977–1983. Foege's book recounts key moments in his career through an enthralling series of stories from a life in public health.

In this Q&A, Foege touches on the challenges of leadership, dealing with politicians and a core part of the public health mission: social justice.

Why did you decide to write this book?

I, a long time ago, decided that I would put off writing until I had some experience and had a chance to teach, and then, writing would be the third and final episode. Some of these stories [in the book] are so interesting to me, that I said, “I don’t want to do a history of the CDC, or even a history of public health, but just to relate some of the stories, that I found, most intriguing, over the years.”

What was your goal in telling these stories?

My objective was to have something for students. An idea of what public health is like, and how there’s real science behind it, but, in many cases, you have problems with the political overseers. Other times, you have problems with the marketplace. And other times, the science just isn’t far enough along to give you a clear and ready answer. Yes, the stories are really aimed at students, trying to [give them] a realistic view of what public health practice is like.

You mentioned dealing with politicians. In the book, you recount some pretty bruising interactions. What are your lessons learned for dealing with politicians as a public health leader?

There’s no question that the politics and public health are so closely aligned that we don’t actually make decisions in public health that don’t have some basis in politics and law. One has to learn out to navigate political systems.

I think that the politicians have the unfair advantage in that they have a power that scientists don’t have. It’s a matter of learning how to live with that imbalance and to provide information politicians need to make good decisions.

Politicians—they’re obviously expert at shaping public opinion and have the ability to do so. They can make comments without nuance that scientists often have to bring to the discussion. Do you see that at a special disadvantage that the scientific community is up against?

It’s true, and in addition to that, they have the power to the purse. Public health [agencies] are totally dependent on government to provide the funds that they need. Public health doesn’t go out … to raise their own money. They’re dependent on politicians. That is a disadvantage. On the other hand, I hope I make clear, there were a large group of positive politicians who wanted to see an improvement in health, and they were able to use those powers in very constructive ways. Both Republicans and Democrats.

Any advice for young public health leaders in terms of how you can encourage and help politicians make the right decisions?

It’s the deep, intensive effort that’s worth it. Trying to figure out, what do politicians need to know, before they make a decision? One of the things I emphasize in talking to public health people, these days, I say, “Some of you should go into politics.” It’s much more efficient for a public health person to be in politics than it is to try to provide information to politicians who may turn over very quickly.

In the book, you advise young people against having a life plan. How then should young people plan for a rewarding career in global health or elsewhere?

I tell them not to have a life plan because of the fact that they cannot possibly understand the opportunities that will be presented to them. You just can’t possibly think of that, but I tell them, spend their time on a life philosophy so that they know what it is, that’s important to them, what their priorities are, and that they have principles that help [them] in every fork in the road make the decision in which way to go.

It’s not having no plan, at all—it’s spending your time on philosophy and then making decisions based on that philosophy.

And then the opportunities will follow?

That’s right. The philosophy of science is how to break down the walls of ignorance and get new truths. The philosophy behind medicine is the question of how to use the truths for every patient you have. And the philosophy behind public health is how to use those truths for everyone.

The bottom line turns out to be social justice. Once you’ve decided on that, as a philosophy, there are so many opportunities, that the problem is how to make choices.

That idea of social justice and health equity is very much a part of the public health conversation today. Do you think some people would be surprised to see that it’s long been part of that conversation?

I think so. I think even some people in public health. I once remarked, when I was at CDC, that in the hallways the people I would meet looked very much like the campus radicals of the 1960s who were anti-government. Here they were working for government. I don’t think they had expected to do that but because they were interested in social justice, this is one way that you can actually achieve social justice.

After you became director of the CDC, you reorganized the agency. What was your philosophy behind that?

A consultant had looked at the CDC and the way it had developed, after the second World War, and he said, “You know, this is really a Mom and Pop operation, but it works.” But he said, “I don’t know that it will continue to work” because quite literally, every time we had an outbreak, we had to go in to a new form of management. That is, we would get people from epidemiology, we’d get people from the lab, and we would [form] a new group on that particular outbreak.

We decided to, instead of organizing around the professions, epidemiology, statistics, and so forth, to organize around outcomes. We have a center for infectious diseases. We eventually got one for chronic diseases. One for environmental health, so forth. In each one of those, we then put in the required professionals. So, you had statisticians, in each of the centers, rather than a statistical bureau, where you had to borrow people, each time you wanted to solve a problem.

The idea came, really by having an outside group look at morbidity [and] mortality in the United States, and tell us, what they thought, our priorities should be. We actually added 3 more priorities to the 12 they had come up with. We said, “In every budget cycle, let’s look at these 15 priorities, and make sure that we are adequately funding them before we start doing other things.”

It really did give us a sense of purpose, and we’ve continued, at the CDC, to basically follow that approach, that your outcomes, drive everything else.

Do you see that reorganization as a successful?

I think it turned out to be very useful.

Is there one thing that you would point to that you did not succeed in as a CDC director, and what was your lesson learned from that?

I continue to worry a lot about vaccines because I think vaccines really do constitute the foundation of public health and it’s been true ever since 1796 with Edward Jenner. And we’re in a position now where people are concerned about, “Do vaccines cause problems?” What’s so frustrating about this is most of that concern comes from an article by Andrew Wakefield, and we now know that it was falsified. Even though we know that vaccines have nothing to do with autism … we’ve not been successful in communicating that to everyone.

That’s one of my real frustrations. I suppose another frustration would be [that even] as far as we were able to go in global health, there were always limitations of what we could do because we had to justify everything on the basis of what it did to the health of Americans. And a better way of looking at this is that a healthy world turns out to be good for America for a lot of reasons. In those days, it wasn’t that clear that Congress wanted to take that approach.

I think the Bill & Melinda Gates foundation has helped to settle that in many ways and for me that’s the tipping point of global health about the year 2000 when they got involved. Now, people pretty much accept that global approach. We’re all in this together. That’s the way to go.

Ed. Note: This is the third installment of a Global Health NOW series on public health leadership.

Join the tens of thousands of subscribers in more than 100 countries who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest US and global public health news. Sign up for our free weekday enewsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues:http://www.globalhealthnow.org/subscribe.html

Former CDC director Bill Foege recounts a life in public health in his new book, “The Fears of the Rich, The Needs of the Poor.” (Image: Courtesy)