Live from New York, It's #CUGH2018!

The center of the global health universe shifted to New York the weekend of March 15-18 for the Consortium of Universities for Global Health.

Naturally, Global Health NOW was there.

Following are some of the essential or at least super-interesting news stories from the day.

To put things in perspective, we begin with this Q&A with Keith Martin, MD, PC, CUGH's executive director, who maps out the latest global health challenges in an exclusive Q&A with GHN.

- #CUGH2018 Warm-Up with Keith Martin (Friday, March 15)

Saturday, March 17

The Winners of the 2018 Untold Global Heath Story Contest, Revealed!

CUGH, NPR’s Goats and Soda Blog, and Global Health NOW of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Global Health selected two winning entries from over 150 thought-provoking entries. It’s the fourth year of our annual competition, which seeks to identify and give a platform to neglected, underreported issues in global health.

For 2018, NPR’s Goats and Soda blog will report on the recruitment of children in Colombia for cocaine production, proposed by Athena Madan, and Global Health will highlight hemophilia in developing countries, Chris Bombardier's idea.

Read more about their ideas and this year's contest here.

Reproductive Justice Centers on Respect

“No providers come into this work for purpose of abusing women.”

That statement, from Lynn Freedman at a #CUGH20-18 panel on reducing disparities in maternal health care, resonated deeply with the audience, which included people around the world engaged in improving birth experiences and outcomes for women. Because even though providers go into the field with the best of intentions, too many women leave the hospital after giving birth and say, “They don’t respect us.”

It's an issue that has always simmered below the surface, but gained more attention following the Center for Reproductive Rights Failure to Deliver report, which exposed disrespect and abuse in a Nairobi hospital, explained Freedman, a professor at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health. But, the problem extends beyond Kenya. And, in the US, many of the women suffering the most disrespect and abuse at the hands of providers are women of color.—Dayna Kerecman Myers

Avoiding the Terrible in North-South Partnerships

He’s seen the good, the bad and the terrible in north-south collaborations.

Peter Donkor, president of AFREHealth and a surgery professor at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, drew on his experiences to offer some lessons learned during a Saturday afternoon session at #CUGH2018.

A couple of the bad and the terribles:

- A KNUST-Canadian university partnership to train Ghanaian PhDs in Canada failed when 4 students admitted to the program never returned to Ghana after leaving.

- A Northern researcher damaged relations when the researcher published results without referencing a KNUST pharmacology professor who had been a key collaborator.

However, Donkor assured the audience that there have been many successful partnerships, including the Medical Education Partnership Initiative and Health-Professional Education Partnership Initiative (HEPI).

“Let’s build on achievement of these collaborations… . And, let’s look after each other,” Donkor said. “When a good seed is sowed, it grows and it grows.”—BWS

Read the full story here.

Fogarty Survives to 50

Last year, Roger Glass, director of the Fogarty International Center, wasn’t sure his organization would survive to see its 50th anniversary this year.

With its $70 million budget targeted by the Trump administration’s proposed 2018 budget, the Fogarty Center faced elimination.

Then something interested happened.

“The hue and cry was tremendous in support of the center,” said Glass during a Saturday morning session at #CUGH2018. “We wouldn’t be here today without such enthusiasm and support from the global health community.”

The “hue and cry” reached led to articles in The New York Times, STAT, USA Today and other publications. With some additional support from Congress, Fogarty has expanded its research to chronic disease, global health security and other areas, Glass said, noting that Fogarty has sponsored more than 1,000 fellows and scholars over the years.

“10 years ago, our communications director said we were the best kept secret in [global health], we are no longer,” Glass said. “And we are alive and well today.”—BWS

The Great Equity Debate

There are 2 key maxims for survival: Never invade Russia in wintertime. And, never debate Richard Horton.

Cheryl Healton, dean of NYU’s College of Global Public Health, presumably respects the former but avidly disregarded the latter as she engaged the Lancet’s editor-in-chief in a vigorous debate about equity in a Saturday morning #CUGH2018 plenary.

She was tasked with supporting this statement: “Equity is the defining objective of global health in the 21st century.” Horton with rejecting it.

Healton opened by vigorously arguing for equity because it is a key social determinant of human health and a stabilizing force in societies that make it possible for people to pursue the futures they want.

Horton responded: “In this wounded world of ours ... [the] goal, the defining objective of global health is not equity. It is to remove the chains that enslave humanity. Liberty is the acid that will dissolve those chains.” —BWS

Who won? Read the full story here.

Friday, March 16

Leading to Equity

Years ago, when Nancy Glass tried to submit an article on strangulation and domestic violence to the Journal of Emergency Medicine, she got a firm no-unless she listed a physician as the author, that is. Senior author.

Glass, now the professor and associate director of Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, reluctantly agreed-although the doctor listed didn't really do anything. The paper was accepted, but that is something she refuses to do anymore.

Miriam Mutebi, Kenya's only female breast surgeon, has some stories too. Imagine running through all the details of your patient's treatment, only to have the patient turn to a male colleague and ask, "So what's the plan, doctor?" Mutebi has also heard of female medical students being asked to sign statements that they wouldn't get pregnant as a condition of acceptance into residency programs.

Clearly, when asked to share examples of women's barriers to career growth, the panelists had horror stories galore. And while the "burden of care is on women, explained Michele Barry, senior associate dean, Global Health, at Stanford University "they're not at the table." But the real goal of the session was to set out tangible steps to increase women's leadership in global health. Read more about the ideas shared here.

Barry also emphasized that we need men at the table; men shouldn't shy away from events like this thinking they aren't welcome. She encouraged women planning to attend the next Women Leaders in Global Health conference (planned for London in November) to bring a male friend.

—Dayna Kerecman Myers

The Most Underappreciated Public Health Threat

The authors of last fall’s Lancet Commission on pollution and health report have 2 shorthand ways to demonstrate pollution’s impact:

- Pollution kills an estimated 9 million people each year.

- Pollution kills 3X more people than AIDS, TB and malaria, combined.

The quick gauge on pollution’s impact, they found, is necessary because people often don’t connect the impact of pollution on human health. They don’t understand pollution’s role in noncommunicable disease deaths, said Philip J. Landrigan, author dean for Global Health at the Ichan School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, during a Friday afternoon session at #CUGH2018.

Landigran, who was joined by Pure Earth’s Richard Fuller and others in preparing the October 2017 Lancet report, notes that “pollution is not fair.” It falls mostly on the poor, minorities, children and others who can’t afford to avoid it: 92% of pollution deaths are in low- and middle-income countries.

Other facts highlighted by Landrigan:

- Household air pollution kills 3 million people per year.

- Ambient air pollution kills about 4 million people per year.

- Polluted water and sanitation kills about 1.7 million people per year.

- Lead kills more than 500,000 per year.

—Brian W. Simpson

3 Things Africa Needs to Do to Help Its Seniors

At age 60, Germans can expect to live almost a decade longer than Nigerians.

What can be done to help Nigeria and other African countries help their seniors? Isabella Aboderin, a senior research scientist with the African Population and Health Research Institute, offered 3 suggestions during a Friday afternoon session at #CUGH2018.

First, Africa’s health systems need to increase their geriatric knowledge. A majority of countries in sub-Saharan Africa have no geriatricians at all, Aboderin said. Only 2 countries (South Africa and Botswana) have more than 5 geriatricians.

Second, the health of older adults need to be connected to Africa’s core population and economic development agendas. Currently, for example, the health of older adults is completely omitted in the African Union’s Africa Health Strategy, she said.

Finally, the debate on universal health coverage needs to recognize that essential health packages must embrace a lifecourse approach.—BWS

Get Ready for the Gray Wave

A century of public health success is creating the challenge of the 21st century.

Consider: By 2050, more than 40% of the world population will be over the age of 60.

“That is a triumph. It’s what we wanted to do, [but] no country is fully prepared” for the consequences, said Linda Fried, a geriatrician and dean of the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, as she set the stage for a Friday afternoon #CUGH2018 session on disparities in healthy aging.

Many developing countries, Fried said, are going to age to same degree in 40 years that Western countries and Japan took 100 years to accomplish.

And the global numbers are staggering. In 2030, there will be 1.4 billion adults 60 and over. By 2050, that number will be 2.1 billion, Fried said.

It’s time, she said, to design the 21st century to be a world that supports longer lives. “The creation of healthy aging is within our collective reach,” Fried said. —BWS

“The World Is Actually Worth Saving”

Stephen Lewis opens #CUGH2018 (Image: Brian W. Simpson)

Stephen Lewis brought eloquence, indignation and a dash of humor to his opening keynote as he stoked motivational fires for #CUGH2018 attendees on Friday morning.

“If Dickens were still alive, he would say, “It was the worst of times. It was the worst of times,” Lewis said, drawing rueful laughs from more than 2,000 attendees.

He then led the audience through a litany of global health threats and disasters: from the nearly 6 million under-5 children who die annually to TB, climate change, and manmade disasters in Syria, Myanmar and Yemen.

He implored global health academics and professionals to take action. “It is necessary to take a stand, let impatience by your byword,” he said. “You must shed your inhibitions and speak truth to fossilized establishment.”

The 80-year-old global health legend closed with a simple plea, “The world is actually worth saving.” —BWS

Read the full story here.

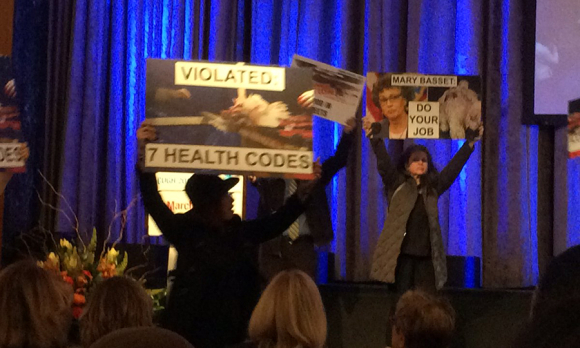

Protestors Fowl Up Health Commissioner’s Speech

Brian W. Simpson

Mary Bassett, New York City health commissioner, was speaking at a health disparities session on Friday morning at #CUGH2018 when a dozen protesters entered the hall and shouted her down. Bassett had just begun her talk about the city’s diversity (40% of New Yorkers were born in another country) and disparities when the animal rights protesters began chanting “Chicken blood is everywhere / Mary Bassett doesn't care.”

The group was apparently protesting an Orthodox Jewish ritual called Kaporos that transfers sins to the birds before they are killed. The ritual claims 50,000 chicken lives each year in the city, the New York Daily News reports.— Brian W. Simpson

Thursday, March 15

Sobering, Stunning Films Frame #CUGH2018

Moving the Pulitzer-CUGH film festival to the first night of the conference helped set the tone for the work ahead—with powerful visual storytelling. Talented filmmakers shared their efforts on topics ranging from attacks on health workers in Syria, to the tragic toll of untreated snakebites, to the disproportionate toll of lead pollution on children.

CUGH and the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting choose and highlight films that amplify global health problems that might be well-documented in academic circles, but need and deserve a bigger platform.

You didn't have to be there last night to see and share these stories that deserve the widest possible audience. Here's a sampling:

The New Barbarianism -- Directed by Stephen Morrison & Justin Kenny

Minutes to Die - Snakebite: The World's Ignored Health Crisis - Directed by James ReidPollution: A Global

Health Crisis - By filmmakers Catherine Orr and Elena Rue - Storymine Media

Venezuelans Suffer Deadly Scarcity of Food and Medicine - By Special Correspondent Nadja Drost and videographer Bruno Federico

Domestic Abuse in Russia - By Special Correspondent Nick Schifrin and videographer Zach Fannin

Schifrin and Fannin's standout film, inspired by a tattoo artist in Russia helping women abused cover their scars with art, brings home why domestic violence is so entrenched in the country. It's a carryover from WWII, women told him: After Russia lost so many men to the war, it was drilled into women that they should be grateful they have a man, even if his "hands get loose" sometimes. Other people told him they don't want western values against domestic violence shoved down their throats. At a time the government is easing the laws, making domestic abuse an administrative, rather than criminal offense, some women are starting to speak out—and Schifrin and Fannin captured their bravery in this film.—Dayna Kerecman Myers

iStock