The Opposite of Martin Shkreli: Drug Development Without Profit

Dr. Ahmed Fahal, of the Mycetoma Research Center, and Nathalie Strub Wourgaft, of the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative, examine patients to learn about their experiences with mycetoma. Neil Brandvold/DNDi.

Part III: The trial

It’s November, harvest time in Sudan, but the land looks lifeless. Cracked, dry earth lies flat until the horizon. Hard lines of squat, rectangular buildings made of mud bricks, and tumbles of dry acacia branches bearing 2-inch long thorns, occasionally break the monotony. Two boys in white tunics draped down to their calves pause to watch a van approach. There is no road. Only space. The driver shouts to them in Arabic, and one boy dashes away. The driver asks the boy who has remained for directions to a health clinic, and he responds in broad gestures.

From inside the van, Nathalie Strub Wourgaft watches the scene unfold in silence. She looks tired, and a little tense. Wourgaft is the medical director of a Geneva-based organization devoted to developing treatments for syndromes that afflict the poor, called the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), and she is in Sudan for just 3 days to scope out the setting for a clinical trial that will be the first of its kind.

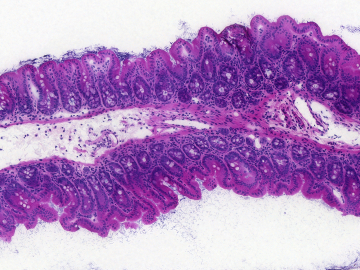

By May, Wourgaft and a Sudanese surgeon, Ahmed Fahal, hope to test a new drug for a potentially lethal, flesh-eating fungal infection called mycetoma. It begins with a cut—a prick of an acacia thorn, perhaps—that is infected by a fungal spore. Even though mycetoma is fairly common in some parts of Sudan, it will not be trivial to find study participants because they must have recent infections, which would be more likely to respond to the new drug, Fosravuconazole. Most of the time, Fahal only sees patients once their limbs are swollen, lumpy, and filled with fungus that protects itself from drugs and the immune system with hardened encasements. So Wourgaft and Fahal have come to this desolate belly of Sudan to see if they can find people with recent infections that might be cured with anti-fungal medicine.

But in November, villagers are tending plots of corn, beans, and other crops irrigated by the Nile River. Although Fahal sent word of his visit in advance, he’s worried the turnout will be low.

Another obstacle is that DNDi’s study budget is less than $2 million. That’s nothing in the drug development world: Pharmaceutical companies spend roughly $1 billion to make and test a new drug. Plus, their studies tend to be conducted in places with well-staffed and supplied hospitals; places where patients drive to clinics on paved roads. But DNDi has decided to do what they can despite the challenges. After all, mycetoma is just the sort of disease that triggered the organization’s founding by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF or Doctors without Borders) in 2003. MSF needed drugs for diseases that afflicted their poorest patients, and no one was making them because they’ll turn no profit, and the company will not recoup the money they’ve invested. In a report published in 2001, MSF found that so-called neglected diseases accounted for 12% of health problems around the world, but only 1.1% of the new drugs developed in the 25 years prior were intended to treat them.

None of that slight fraction goes to mycetoma. But that’s about to change. “Even if we do one short project, perhaps the machine will start and others might pick up on it later on,” Wourgaft says. “But if no one starts, the chances that nothing will happen are really high.”

People who farm and herd livestock in central Sudan are at risk of mycetoma because thorns prick their skin as they walk, and that can allow flesh-eating fungi to enter. Neil Brandvold/DNDi.

Wourgaft met Fahal in 2010 at the request of a mutual colleague. “Professor Fahal told me, mycetoma is neglected even by the Drugs for Neglected Disease initiative,” she recalls. “And when he said that to me, I felt bad but it was true.”

During the next 2 years, Fahal and staff at DNDi plotted how they might push mycetoma research forward despite a dearth of funds. In 2013, DNDi connected a Japanese pharmaceutical company, Eisai, with Wendy van de Sande, a mycologist at Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam. Eisai owned a drug with anti-fungal properties, Fosravuconazole, and they agreed to send samples of the active ingredient in the compound to van de Sande. Soon after, she reported that it killed more colonies of mycetoma fungus grown in petri dishes than several medicines currently used to treat the disease

The finding boosted Fahal’s spirits. He had been amputating a limb every month or so from patients whose bones had been devoured by the flesh-eating fungi. And he was drained from delivering bad news when patients’ conditions did not improve after taking the main drug used to treat mycetoma, itraconazole. In one small observational study, Fahal and his colleagues reported that only one out of 13 patients was cured after a year of that treatment. Most of the others still required surgery. The results might have been better if patients had been at earlier stages on the disease—but that study has never been done.

After further laboratory experiments, and several international meetings, DNDi announced that Eisai would donate Fosravuconazole pills for a clinical trial slated to launch around May 2016. The plan is to enroll 138 people diagnosed with early stage mycetoma in Sudan. Neither patients nor Fahal and his team will know whether they are given the current treatment, itraconazole, or the new drug. During the course of a year, his lab will take digital photos of infected limbs in order to monitor and compare the effect of the 2 medicines over time.

“This will be the first ever proper clinical trial on mycetoma that will include a lot of quality measurements,” Fahal says. “I’ve been waiting for this for 30 years.” He plans to hang a photo of Wourgaft on the wall of the Mycetoma Research Center he founded in 1991, with a caption naming her an ambassador of the disease.

However, it’s not a given that patients will volunteer for the study. Those who are not yet crippled by the disease may not want to take the time off from work or childcare for trips to Khartoum. They might stop taking the pills midway through the trial. They might not care for Western medicine. The road trip in central Sudan was meant to uncover invisible obstacles like these.

Badria Abdulrahman's leg was amputated after mycetoma fungi destroyed the bones within. She cannot enroll in the upcoming clinical trail to test a mycetoma drug because her disease has progressed, but she still calls the study marvelous because it "will be good for the community." Neil Brandvold/DNDi.

When the driver parks the van beside a concrete building where a handful of men, and a dozen women wrapped in colorful shawls linger, Fahal and Wourgaft charge out of the vehicle to greet them. They enter the building—a health center in the village Shadida Agabna—and share a wooden bench inside. A crowd has gathered in anticipation of Fahal’s visit. He has offered consultations on any infections that could be mycetoma. With the coolness of a medic, Wourgaft places the swollen foot of a woman on her knee. The foot is scarred from surgeries meant to excise the mycetoma fungus growing within. Wourgaft slides her black rimmed glasses down to the tip of her nose, and asks Fahal to translate her questions into Arabic: When did you notice the infection? Have you taken medicine? How have you faired? “I am trying to understand the perspectives of patients,” she tells me later. “I’m wondering if they would enter a clinical trial, and what would be their barriers for entry? Do we need a car to bring patients from here to Khartoum every month?” She says, “You need to anticipate what could go wrong.”

Fahal points out contours of tortured limbs, and tells Wourgaft what his trained eye sees in them. They proceed like this for an hour, during which time more people drift into the building. Among them is a 60-year old health worker named Mona Ali who has worked at the center for 27 years. She calls mycetoma by its older moniker, Madura Foot, named after a town in India where British doctors reported the disease in the 1800s. Ali says Madura Foot is common among people who herd goats and cows. A woman adorned in a pink cloth enters the center in a wheelchair. She has met Fahal before, and he examines the stump of her amputated limb. She does not qualify for the clinical trial because her mycetoma had progressed so far, but still, she says, “The study is marvelous, it will be good for the community.”

Then suddenly the visit is over. Fahal corrals the team back into the van. The mood has lifted, and he and Wourgaft seem elated as the van rumbles across the barren landscape. Even during the season when people are far more likely to head to farms than a health center, they identified a man with an early-stage mycetoma infection—exactly the type of patient they seek to enroll in the trial. The others in the village were too far along. “I want them to have a fresh lesion that is less than 10 centimeters in diameter, no previous surgery, no previous treatment, and more than 18 years of age,” Fahal says.

Fahal and Wourgaft spend the next day meeting with colleagues and officials. It appears that regulatory authorities and the ethical review board in Sudan will support the study—another relief. Wourgaft decides to import a blood chemistry machine to test patients’ liver function so that they will detect drug toxicity before it causes damage. And she and Fahal plan a small study to estimate the disease’s burden in the country because at the moment, no one knows how many people have the disease. They eat dinner at a long table in a Lebanese restaurant in Khartoum, and continue to hash out the details of the trial on the restaurant’s front steps once the bill is paid. Wourgaft’s flight leaves just after midnight, and her colleague gently urges her to end the conversation and return to the hotel to pack. Is she anxious about the trial? “I just want to start,” she says, “that’s my only concern.”

Later, reconsidering her statement, she adds, “I do have one big fear—that the drug will not work, and that is serious since we have nothing else in the pipeline, and that’s terrible because we create a lot of expectation by doing a trial, we raise peoples’ hopes, and if we fail, we have no backup. Zero. Nothing. Nada.”

But at least the engine of research has begun to rattle.

Correction: Originally this article incorrectly stated that Eisai had shelved Fosravuconazole because it was ineffective against the disease it was originally intended for. In fact the drug is not shelved and is still in development.

Read our intro to the series and follow-up pieces.

If you'd like to donate to mycetoma research in Sudan, you can do so here, through the Sudanese American Medical Association.

If you’d like to donate to the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative, which is developing new treatments for mycetoma and other neglected diseases like sleeping sickness and pediatric HIV, you can do so here.

Please join the thousands of subscribers who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday enewsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues: https://globalhealthnow.org/subscribe