First Step for a Dreadful Disease: Get on the List

Part II: The list

Grocery lists remind us to buy eggs. Wedding lists identify guests. Bucket lists record the things we want to do before we die. Lists bring into focus priorities that might be lost in the whirlwind of existence. So tasked with juggling a jillion aspects of health that comprise the wellbeing of all people everywhere, the World Health Organization makes lists too.

One of the WHO’s lists enumerates 17 neglected tropical diseases, otherwise known as diseases of poverty because of the people they generally afflict. Too poor to afford drugs, patients with this set of diseases are ignored by pharmaceutical companies who must turn a profit. Neglected diseases are largely sidelined by major US and European funding agencies because the ailments almost exclusively hurt people in far-off continents. For similar reasons, the diseases are neglected in the media because people who are rich enough to get their news from the Internet or TV are essentially not at risk. But at least 17 neglected diseases are not utterly forgotten because they’ve landed on the WHO’s list.

However, a very neglected condition caused by flesh-eating microbes in equatorial countries is not on this list—despite years of advocacy. At a meeting to be held in late January, board members at the WHO will decide whether to take the first steps in making this scourge, called mycetoma, number 18. More specifically, they will determine if mycetoma’s addition can be a topic of conversation at the World Health Assembly in May, where representatives from 194 countries meet to decide global health priorities for the coming year. Even if the WHO puts mycetoma on the meeting’s agenda this January, country representatives could still vote to exclude it from the list in May. After all, the addition would come at a cost because as the list grows, so too does the WHO’s workload.

Why would an ancient, debilitating, and very neglected disease not qualify for the WHO’s list? One reason is that so few studies have been conducted on mycetoma that no one knows how many people have it. That said, it’s been documented in 23 countries—Sudan, India, and Mexico seem to have the most cases. And based on somewhat anecdotal information from certain regions, such as a village in Sudan where 4% of the population of 700 has mycetoma, researchers believe the condition is not ultra rare.

“We feel very strongly that mycetoma’s burden is underestimated,” says Nathalie Strub Wourgaft, medical director at the Drugs for Neglected Disease initiative (DNDi) based in Geneva, Switzerland.

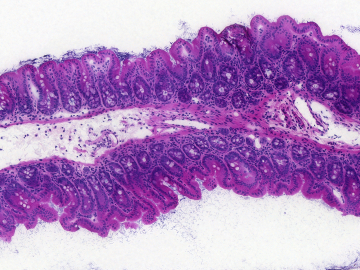

Another strike against mycetoma (in addition to those shared by all diseases of poverty) may be that the worst variety of the condition is caused by a fungus that only a horror movie director could love. The ugliness of what it does to the human body causes the average person to turn a blind cheek. Mycetoma begins when a person’s skin is pricked by a thorn or otherwise cut, and then a spore enters the wound and sprouts filaments that crawl through their flesh. Over the years, the fungus eats away at bones and tissue, filling the infected appendage with clusters of hard grains that are impervious to a person’s immune response or drugs. Lesions ripple across the person’s skin, leaking pus, fungi, and foul odors. The afflicted become increasingly disabled and forlorn. Amputation is common.

Mycetoma is not the only mysterious flesh-eating fungal disease. Take zygomycosis: In 2011, five Missouri residents died of this fungal infection in 2011 after a tornado lifted zygomycetes spores from the dirt. Airborne, the fungi burrowed into the mucosal lining of victims’ noses, from there into their eye sockets, and finally their brains. Relatively little is known about this infection too—but it’s rare compared with mycetoma.

Collectively, however, life-threatening fungal infections harm millions of people worldwide, says University of Missouri mycologist Theodore White. This group of maladies particularly afflicts people with weakened immune systems. It includes oral thrush from Candida fungi, which preys on HIV-positive people, and Crytococcosis infections that can overwhelm organ transplant recipients who have been given drugs to prevent their immune response from attacking foreign tissue. And yet, White adds, fungal infections are overlooked. Just 1.4% of the UK Medical Research Council and Wellcome Trust budgets, and 2.5% of the US National Institutes of Health budget for immunology and infectious disease research, went to medical mycology between 2008 and 2012, according to a report White co-authored in Science Translational Medicine.

Since mycetoma is excluded from the WHO’s list, the handful of scientists who want to fight the disease find themselves in a catch-22. “The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the [European funding agency] EDCTP only fund diseases on the WHO’s site,” says Wendy van de Sande, a mycologist at Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam who studies mycetoma with small grants she says she’s won based on her own merits rather than mycetoma. “When I apply [to big funders], I usually hear, sorry, this disease is not considered important” because it is not on the WHO’s list, she says. “And the WHO makes the point that it isn’t on their list because we don’t know how many people have the infection.”

To figure out mycetoma’s burden, van de Sande has tried to coordinate epidemiological studies but she has failed to find the funds to do so.

Researchers and doctors who work with mycetoma are prone to moments of profound pessimism based on years of disappointment. “It is neglected and it will stay neglected because no one gives money to research it,” van de Sande says. “If they did, we might be able to solve this in a few years.”

Her statement may be an exaggeration because not all fungal diseases are easy to fix. That said, there’s no way to know without trying.

In 2013, a barrage of advocacy from Ahmed Fahal, the founder and director of the Mycetoma Research Center in Sudan’s capital Khartoum, and his colleagues paid off. The WHO agreed to add the condition to an addendum on their website called “Other Neglected Diseases.” Together with a hodge-podge of problems, such as snake bites, the addition didn’t exactly do anything—but it did signal progress.

However, the WHO has since brushed off mycetoma along with the “Other Neglected Diseases” category. Mycetoma’s mention is now curiously buried at the bottom of a WHO webpage on Buruli ulcer, an unrelated parasitic disease on their neglected diseases list. When asked why the move occurred, a WHO spokesperson replied that “as in the case of Buruli ulcer, early detection and treatment of mycetoma are important to reduce morbidity and improve treatment outcomes.” In other words, they’ve decided to focus on the shared root of mycetoma with other problems. For example, a lack of clinics and health providers in poor and rural regions means that patients will not see doctors until their diseases have reached a point of no return.

Indeed, the vast majority of doctors and hospitals in Sudan cluster in the capital city. On Mondays, Fahal and his staff see patients who have sometimes traveled for days to reach their appointments. Within an hour at the clinic, I talk with women who herd camels across the desert, a young man from a famine-prone area in central Sudan, and a teenager from a conflict-ridden village near Darfur. “My mother could not be taken to the hospital when she gave birth to me because the trip was too dangerous,” says the teen, AbdelLotif AbdelRahim. Well-stocked clinics are rare in his region because it’s so unsafe. When AbdelRahim’s foot swelled with an infection earlier this year, his family decided to invest in his long trip to Khartoum. Someone else in the village had an amputated leg resulting from mycetoma, and they didn’t want the same for their son. “If I was brought up in a different family, by now my leg would be gone,” AbdelRahim says. But his infection is slight compared to the patients around him, and a laboratory technician tells me he will likely be cured with the drugs they have on hand.

So, as the WHO says, if mycetoma were caught early, it wouldn’t take such a toll. What’s more, a functional health system—and development in general—might prevent the ailments that may make people vulnerable to the disease. Most dangerous fungal infections prey on people who already have immune systems weakened by diseases like HIV or malnutrition. So do you fight underlying problems by providing preventive care, or the opportunistic infections that pile on top?

Dirk Engels, director of the WHO’s neglected tropical disease department in Geneva, worries that a list of specific maladies could distract people from systemic deficiencies that lie at the heart of all diseases that afflict the world’s poorest, such as a lack of health care, clean water and sanitation. “The list is getting longer,” Engels says, “there were 12, then 17—and I think that mycetoma might be added to make 18—but we want to move away from these numbers because they are becoming counterproductive.”

A second problem with listing diseases like mycetoma—in which the burden is unknown, treatment lousy, and prevention measures not understood—is that the WHO is not able to recommend specific interventions for the condition as they do with other neglected diseases on the list. For example, to combat the neglected disease rabies, the WHO recommends better access to the rabies vaccine, to antibodies after a bite, and vaccination for dogs in areas with a high prevalence.

Wourgaft, the DNDi medical director, understands the WHO’s reasons for hesitation. She agrees that we can’t wipe out diseases of poverty without big-picture “horizontal” solutions like clean water and reliable health systems. Nonetheless, mycetoma will remain obscure unless researchers can harness grants to discern the disease’s prevalence and to figure out which drugs treat it best. For that, the disease needs to be recognized by funders. Also, big-picture solutions take time. “Horizontalization is great,” Wourgaft says, “but it’s not for tomorrow morning.”

A list is a place to start.

Read our intro to the series and follow-up pieces.

If you'd like to donate to mycetoma research in Sudan, you can do so here, through the Sudanese American Medical Association.

If you’d like to donate to the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative, which is developing new treatments for mycetoma and other neglected diseases like sleeping sickness and pediatric HIV, you can do so at this link: http://www.dndi.org/donors/donate-support.html

Please join the thousands of subscribers who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday enewsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues: http://www.globalhealthnow.org/subscribe.html