COVID-19’s Stop-Gap Solution Until Vaccines and Antivirals Are Ready

As novel coronavirus cases continue to mount globally, humanity can’t turn to its go-to infectious disease fixes: vaccines and drugs. At least not yet. A new vaccine might be at least 12 to 18 months away though new drug treatments will likely come sooner.

Arturo Casadevall, chair of the Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, is helping organize a national effort to use antibodies from recovered COVID-19 patients for protection and treatments. In a March 13 Journal of Clinical Investigation article, Casadevall and Liise-anne Pirofski of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine proposed the stop-gap measure of using plasma (serum) from the blood of survivors until a vaccine and antiviral medications are available.

In this Q&A with Global Health NOW, Casadevall says clinical trials could begin in 3–4 weeks provided that they clear all the regulatory steps. If that happens, he anticipates widespread availability by early summer.

How can plasma be useful against the novel coronavirus?

When you recover from many viral diseases, you have in your blood what are called neutralizing antibodies. These are antibodies that kill the virus. Once you recover, the plasma can be taken from donors. It’s very safe. It's the same thing as using a blood donation except they don’t take the red blood cells, they take the liquid. They take the plasma. It is itself a drug... it can be used for prevention of infection for people who are being exposed or it could be used for therapy for those who are sick.

It’s not a vaccine. Think about it as the administration of a protein, it’s a liquid that is given to people that gives them immunity.

Right. Because the vaccine would provoke the recipient’s antibodies. You'll have the antibodies, but they won't be your antibodies—though it'll do the same thing.

Right.

And if somebody is already sick, can the plasma help them?

Yes, it can be used for prevention or a treatment.

This strategy is already being used in China?

Yes. In fact, the Chinese sent 90 tons of plasma to Italy.

Will this need to go through extensive testing in the US?

We have to do this right. You need to have [the protocol reviewed by officials in each institution’s review board]. And because this is an investigational drug, you need to have FDA approval to do a trial. And both documents are being sent in today [Wednesday, March 18] to the FDA and to the IRB [at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health]. That's how far along we are.

You know we have gone from discussions to the FDA and the IRB in two weeks.

How long would that normally have taken?

Many, many months.

How soon do you hope to roll this out?

Between three and four weeks.

And what will that look like? A clinical trial?

Once we get the approval, we can begin recruiting people for donating plasma and for the clinical trials. Donors have to donate blood that then has to be processed before using it. I think that it is not going to help the first ones who get sick, but I think as we as we get into trouble in April, May, June, that is that this may be coming online.

Are there side-effects to using this?

Plasma is very safe. It is screened for bloodborne pathogens and blood typed so you don't have a transfusion reaction. Blood transfusion is one of the most regulated industries in the United States. It's one of the safest things available.

How’s what you’re proposing compare with what the Chinese have done?

The Chinese have assumed that everybody who recovered had antibodies so they went on to use the plasma and are reporting good results although the data is not yet published. When patients recovered, they took the plasma and used it on those who needed it. We are proposing a much more sophisticated thing in which we will actually measure the virus-killing antibody in people before they donate. And we’ll use only the highest activity plasma.

You're making sure that there are antibodies in there and that they would be effective?

Exactly. Exactly—that we have a potent unit. We think that one person can treat two people.

When you say it could be ready and useful in three to four weeks—

I'm assuming no major hurdles from the IRB or FDA, right—but everybody's in emergency mode. I mean we are headed for something we have never experienced before and I don't think anybody's going to sit there and obsess on the small details. This is the only game in town.

How will you get this out nationwide?

Our network involves dozens of institutions.

Obviously you wouldn’t be be producing all of this. You would be giving people the directions on how they can do this themselves?

Johns Hopkins is sending this IRB protocol to everybody who needs it to try to expedite things.

Other institutions wouldn't have to go through the same FDA approval, right?

Well, we are hoping that the FDA, given the emergency, grants Hopkins, one investigational new drug [IND approval] that can be used nationally .

You launched this?

I knew that this was potentially very helpful so I wrote an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal that gathered a lot of attention and focused many physicians. My colleague and I then wrote a formal proposal for this option that was published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation. We basically began screaming first. And others noticed, and many groups joined. This was important and needed to be done.

It’s a good story in the middle of a plague.

Ed Notes:

Casadevall wishes to thank Hopkins colleagues who have been working on this project including Shmuel Shalom, Evan Bloch and Aaron Tobian, Andrew Pekosz, Lainie Rutkow, Bryan Lau, Jonathan Zenilman and many others including the Office of the Provost, which supported the effort with a $250,000 grant. He also notes, “This is an all hands effort and the Hopkins community has taken on the challenge with great energy, determination and cooperation.”

For more information on this issue, listen to this episode of the Public Health On Call podcast.

For GHN's latest coverage of the coronavirus, visit here.

Join the tens of thousands of subscribers who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday newsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues: https://www.globalhealthnow.org/subscribe

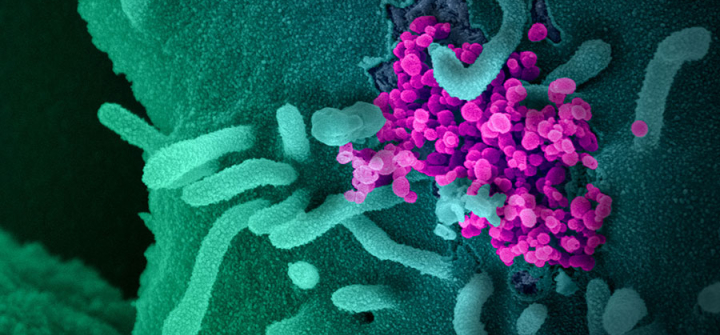

This scanning electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2 (round magenta objects), also known as COVID-19, emerging from the surface of cells cultured in the lab. Image: NIAID-RML