For India’s Women, Safety in Numbers

For Indian airline executive ElsaMarie D’Silva, the gang rape that killed a Delhi college student in 2012 was a turning point.

Although the attack stood out for its savagery, D’Silva knew that the rape of Jyoti Singh Pandey was not an isolated event: it fit a pattern of everyday harassment and violence that Indian women endure in public places. D’Silva knew something of this from her own experience of being molested at age 13 on a jam-packed train in Mumbai—an incident she repressed for decades, until the day a colleague asked her why she avoided public transport.

In India, D’Silva says, “women are always devalued, from the time you’re born—if you’re born, that is, because we have an atrocious sex ratio.” (Extra men result when couples abort female fetuses.) Human Rights Watch recently pointed out that an Indian woman who reports rape to police may still be subjected to a degrading “two-finger test” that supposedly determines whether the woman is “habituated to sex.” In June 2018, a Thomson Reuters Foundation survey of more than 500 global experts on conditions for women ranked India as the world’s worst place for violence against women. But statistics on such violence have been scarce, and unreliable.

After the rape, D’Silva knew that to keep the issue alive, she would need evidence of aggression against women. She established a digital platform called Safecity in December 2012 to crowdsource data on intrusions ranging from catcalls to groping to sexual assault. D’Silva had found her calling: not long after, she left her corporate job as a vice president for network planning at Kingfisher Airlines and began working full-time for Safecity. Since 2014, the site has accumulated more than 12,000 anonymous reports of harassment or violence.

Safecity uses a digital world map to mark each incident with a red dot; clusters of dots pinpoint hot spots. “You don’t need big data,” says D’Silva. “Even 100 reports will identify a trend.” By alerting women to risky areas, the map “allows people to understand the safety landscape of an area,” she says. “They can make the most informed decision for themselves: They can decide on the time of a visit, the method of transport to use, or whether they need to be accompanied by someone.”

Sharing information can catalyze action. “We all live in silos,” says D’Silva, but when incidents accumulate in one location, Safecity informs local communities through partner organizations. Together, they help local people come up with an action plan.

One Safecity project was in an urban village within New Delhi called Lal Kuan, where families have no toilets at home. The public toilets were locked because the local authority refused to maintain them, and women who went into the bushes to relieve themselves encountered men spying on them and taking photographs. They were vulnerable to attacks. Collaborating with a gender resource center managed by Plan International, and accompanied by the media, Safecity confronted local authorities. They promptly opened and cleaned the toilets.

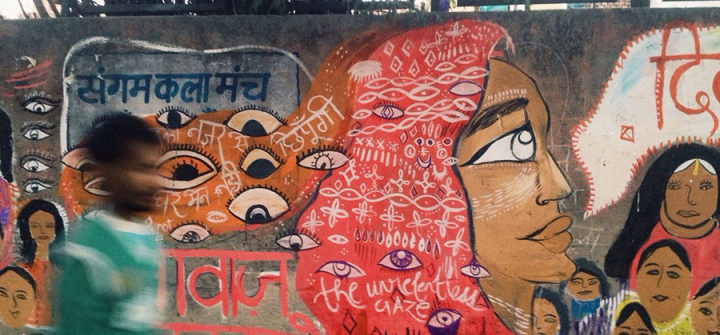

A woman painting a mural with eyes staring back at harassers in New Delhi. Image: Courtesy

Another hotspot in that neighborhood was around a tea stall, where men stared at women and girls who passed by, sometimes making rude comments. “In a culture like ours, you can’t challenge a man,” says D’Silva. But after women from the neighborhood painted a nearby wall with eyes that stare back, and the message “We won’t be intimidated by your gaze,” the stall owner began insisting that loitering male customers move on.

In Mumbai, students entering the gate to Sophia College for Women had no choice but to walk by leering men. In response, Safecity sponsored a mural project directed by artist Jai Ranjit. After attending a workshop on laws prohibiting sexual aggression such as lewd invitations, indecent exposure and stalking, the students painted a mural near the gate quoting sections of the law protecting women and the statement, “Sexual harassment is a crime” in Hindi and English. “The wall mural gave the girls confidence to walk to their college,” said D’Silva.

A mural painted by students at Mumbai's Sophia College. Image: Courtesy

The Safecity site—under the aegis of D’Silva’s Red Dot Foundation—is based in Mumbai, and most posts have come from India. But thousands of women have contributed accounts of violence in Kenya, Cameroon, and Nepal, and, in small numbers, from disparate locations including Malaysia, the United States, and Trinidad and Tobago. In India, community workers upload most of the stories on behalf of women who can’t access computers.

The Safecity platform has been funded by Tata Trusts, Amplify Change, and Society for Development Alternatives, among other groups. “The donors believe in investing in technology to address the issue, as it is a new way to do so,” says D’Silva. Safecity staff also offer workshops for corporate employees, parents, and young people. These workshops have addressed taboo topics including menstruation and how to protect children from sexual predation, along with practical matters such as how to file a complaint to police that will require an investigation, not just a report.

Safecity sponsors group conversations for men and boys as well as women and girls, since an end to gender-based aggression depends on a culture that fosters respect for everyone. “We need men and boys to be part of the solution,” D’Silva says.

Join the tens of thousands of subscribers who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday enewsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues: http://www.globalhealthnow.org/subscribe.html

Near a tea stall in India where men harassed women and girls, women painted a wall with eyes that stare back and the message “We won’t be intimidated by your gaze.” All Images courtesy of Lal Kuan (tea stall) and Sophia College - Red Dot Foundation.