Unsafe Generation: Medical Students in Conflict Zones

Attacks on healthcare services are a cruel reality of today's violent conflicts. The WHO reported more than 320 attacks on healthcare in 2017 alone, while the Safeguarding Health in Conflict Coalition’s recent report, Violence on the Front Line: Attacks on Health Care in 2017, tracks more than 700 conflict-related attacks in 23 countries.

Attention to such attacks usually focuses on the health workers, facilities, and health systems targeted by the vast majority of attacks on healthcare. But there is one key group that has been left out of most efforts to track attacks on healthcare: those training to be doctors.

Health workers all around the world, of course, are the cornerstones of healthcare—without human resources for health, there is no healthcare at all.

Yet, the health workforce must be trained, nourished and educated. Without proper education for healthcare, we skip the first and foremost requirement for strong and resilient health systems. However, the safety of health students, professionals and health facilities, i.e. the safety of medical education, had not been addressed specifically—until the International Federation of Medical Students' Associations (IFMSA) looked at how conflict affects the education of future medical doctors in its report, Attacks on Medical Education—the first in a planned series. The report covers attacks on medical education in 7 countries, including Libya, Palestine, Ukraine, Sudan, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen. It explores the impact of violence on medical education, including education facilities, teaching hospitals, libraries, professors, medical students and all other directly related components.

The findings are sobering.

The attacks have largely taken the form of barriers to access, rather than targeted strikes. In Palestine, students encountered obstacles to obtaining permits that effectively excluded them from training in several specialized hospitals in Jerusalem, which have numerous departments and specialties not available anywhere in the rest of the region. The procedures for students to obtain these permits are very complicated and bureaucratic.

But 55% of medical schools in the 5 most affected countries (Libya, Palestine, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen) were forced to pause their operations during conflicts, either because of unsafe environments or because buildings were physically destroyed. Out of 22 medical schools forced to pause education, 19 resumed once conflicts were resolved or confined, but the rest (Al-Furat University in Syria, Venezuela’s University of Zulia Medical Faculty, and Simferopol Medical Academy in Crimea (annexed territory) were destroyed and forced to halt their training missions. (Simferopol Medical Academy is physically operating, however, the Ukrainian government does not recognize it and students are not able to have their degrees validated.)

Many medical students were given the opportunity to resume their studies in other programs, but that in turn resulted in disproportionate strain on those faculties—which were typically unprepared to absorb large numbers of unexpected students.

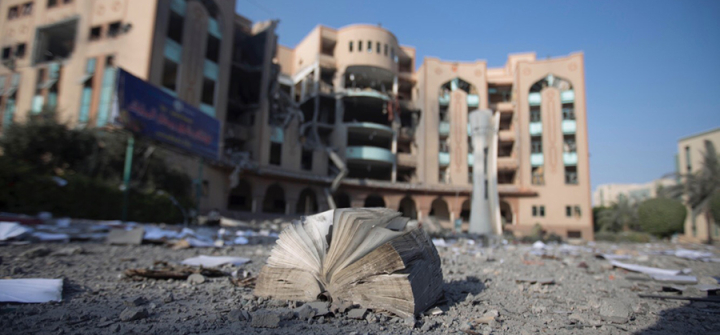

The attacks on medical education affect the initiation, continuation and conclusion of medical studies. The impact ranges from direct to indirect attacks inhibiting students’ access to medical education, from the difficulty medical students in Palestine faced obtaining permits to the cessation of operations across multiple faculties in Libya, Syria, and Yemen. Direct attacks were observed mostly in Syria (with the destruction of Al-Furat University, and attacks on Damascus and Aleppo Universities); Libya (The library of the University of Sirte was burned down); Palestine (the Islamic University of Gaza and its medical laboratories were bombed several times); Venezuela (the shooting and burning of the medical auditorium at the Universidad de Los Andes); and in Yemen (including several medical schools covered in the report).

However, the report also uncovers the incredible resilience of medical students and their teachers. Despite living under the imminent threat of attacks and interruptions, the vast majority of facilities continued to run in some capacity. This proves that violence and war are not strong enough to suppress the drive for education—but people training to deliver medical care should never be a target of such attacks in the first place.

The report points toward more questions to explore, as well. If medical education is so heavily affected by violence, what is the impact of conflict on the sustainability of health systems? And how is training in other professions such as nursing, dental, pharmacy and public health affected as well?

Marian Sedlak is the Liaison Officer for Human Rights and Peace Issues in the International Federation of Medical Students’ Associations (IFMSA). His main areas of work include healthcare in humanitarian settings, attacks on health services, and refugees’ and migrants’ rights and health. He is the final year medical student from Slovakia.

Batool Alwahdani is the Vice-President for External Affairs in the International Federation of Medical Students’ Associations (IFMSA), which represents 1.3 million medical students from 127 countries. She acts as the leader of IFMSA advocacy work and external representation. She is a recent medical doctor graduate from Jordan.

Join the tens of thousands of subscribers who rely on Global Health NOW summaries and exclusive articles for the latest public health news. Sign up for our free weekday enewsletter, and please share the link with friends and colleagues: Subscribe to GHN

The Islamic University of Gaza after it was bombed in August 2014. Image: Mahmoud Al-hams, Agence France-Presse