Malaria: Images from the Pacific

Daw Ngwe Tein, above, is babysitting her 3-year-old grandchild, Blu Nay L'Paw, while Blu's mother works as a Medic in the Shoklo Malaria Research Unit (SMRU) in Mae Sot, Thailand. Pearl Gan, a Singaporean photographer, captured their images as part of a collaborative project with the Oxford University Clinical Research Unit, Eijkman Oxford Medical Research Unit, Jakarta and J. Kevin Baird, PhD, to increase awareness of the plight of people affected by malaria in the Asia Pacific. In her photo essay, Gan describes some of the people she met for the project, and highlights the need for greater attention and treatment options for people suffering from malaria.

SMRU, where Blu's mother works, is a field station of the faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand, and is part of the Mahidol-Oxford Research Unit (MORU) supported by the Wellcome Trust (UK). The main objective of SMRU is to provide quality health care to the marginalized migrant populations living on both sides of the Thai-Myanmar border in the Mae Sot area, Tak Province. This is achieved by research and humanitarian activities, with an emphasis on maternal-child health and infectious diseases.

All images copyrighted by Pearl Gan in association with Oxford University Clinical Research Unit, Eijkman Oxford University Clinical Research Unit and The Wellcome Trust.

Ma Khit Shin, a Karen refugee mother, brings her infant for a check-up at the Wang Pha Clinic operated by the Shoklo Malaria Research Unit. She wears Tanaka tree bark paste, a cooling and sun blocking paste. For most rural people, life is lived almost entirely outdoors under the tropical sun and Tanaka offers protection. Endemic Plasmodium vivax malaria in this area is an important risk factor for poor maternal and neonatal health outcomes. Pregnant women and infants less than 6 months of age cannot be treated with primaquine against multiple relapses of vivax malaria, and vigilance against those attacks is required.

Here, a mother bathes her 3-days-old baby at the Wangpha migrant maternity clinic, operated by the Shoklo Malaria Research Unit (SMRU) at Mae Sot near the border with Myanmar. She and her baby access services offered to relatively few of the migrant populations at border regions across the Asia-Pacific. Human migration linked to labor or conflict in the region involve many tens of millions each year, perhaps as many as several hundred million people, and have been occurring for centuries in densely populated Asia. Authorities often look the other way rather than confront the problem of porous borders. When thus unnoticed or unacknowledged, the people crossing borders effectively become invisible and unlikely to receive assistance or access to health services—they are deeply marginalized and vulnerable to malaria and the associated poor health outcomes.

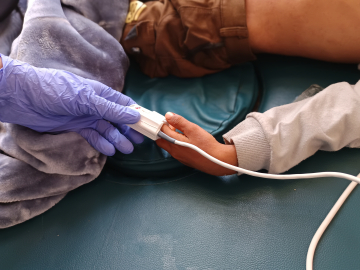

56-year-old Fransura Kavori recovers from an attack of Plasmodium falciparum malaria at the Mebung Primary Health Centre at remote Alor Island in eastern Indonesia. Her nurse, Dian Adiana of the Ministry of Health, takes a follow-up blood sample to check on the progress of her therapy against the infection. Kavori happens to be the malaria volunteer worker and traditional healer of her home village. Traditional healing is a very important element of healthcare in Indonesia, with many dozens of defined herbal remedies for common ailments collectively referred to as “jamu.” Traditional healers, however, acknowledge and understand their limits, as Kavori’s presence at hospital demonstrates. Malaria is well known to be out of the healing reach of traditional jamu.

Vong Phou has been infected with malaria at least once a month for the last 7 years. He is only 29 years old; however since the age of 23 until today his life has been trapped with malaria. He had falciparum malaria 10 times in 2016. All of his previous malaria episodes have been falciparum malaria; however, this current one is a mixed infection (falciparum and vivax). Co-infection like this may be relatively rarely detected by RDTs or even expert microscopy, but it is actually very common in the Asia-Pacific region. More than one half of patients diagnosed and treated for P. falciparum will experience an attack of P. vivax within 2 months that originates from dormant parasites in the liver more often than from a new infectious bite by an anopheline mosquito. Dormant P. vivax infections may be highly prevalent and the source of most clinical attacks by this species.

A Cambodian forest worker, Vong Phou recovers at home from yet another attack of malaria, this time by both Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax. He is dehydrated and exhausted from his malarial rigors of the previous night. It will take him several days to recover from this attack, one of several he suffers each year due to both his high-risk profession and inability to take primaquine to prevent relapses by the dormant forms of P. vivax that rest in his liver. Sometimes he gets malaria as often as twice a month. He always tests his blood when he has a high fever, shivers, strong headache and body aches. Sometimes the malaria infection is so strong that he has been hospitalized for up to 10 days. He often needs to be given intravenous anti-malarials.

A young daughter of refugees on the outskirts of Mae Sot, near the Thai border and Myanmar gathers firewood. Her family is trying to cope with income losses caused by an ongoing shortage of rainfall and the failure of their bean crop. Millions of displaced or migrant people across the Asia-Pacific Region cross borders enter a social and legal limbo that often leaves them without the safety nets of family assistance or government services, including access to essential health care services when seriously ill. Malaria stalks these people with such illness along most of the national frontiers of the region.

©Pearl Gan in association with Oxford University Clinical Research Unit, Eijkman Oxford University Clinical Research Unit and The Wellcome Trust.